Review by Scot Cotterell, Fusion and Appropriation: Dynamism and Flux

To cite this review

Cotterell, Scot. Review of Mix Tape 1980s: Appropriation, Subculture, Critical Style, an exhibition by the National Gallery of Victoria. Fusion Journal, no. 2, 2013.

Mix Tape 1980s: Appropriation, Subculture, Critical Style

National Gallery of Victoria, Australia 2013.

In April, 2013, the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne explored Australian art of the 1980s in an exhibition entitled “Mix Tape 1980s: Appropriation, Subculture, Critical Style”. Featuring over 120 works, the exhibition brought together creative approaches ranging from appropriation and sampling to the DIY aesthetics of post-punk; and from postmodern critiques of authorship and originality to postcolonial revisions of Australian history. On exhibit was a wide mix of media — painting, sculpture, photography, drawing, fashion and furniture design, as well as selected ephemera including magazines, records, films and video which reference the preoccupations of a rapidly changing Australian society and the intersections between art, music, theory and popular culture. Commenting on the connections and appropriations of the decade, Max Delany, Senior Curator of Contemporary Art, commented that while the 1980s were characterised by significant events such as the AIDS crisis, the 1988 Australian Bicentenary and the fall of the Berlin Wall, they were equally memorable for raging debates between divergent camps and subcultural groups concerning art and culture:

“The 1980s was a period in which artists took up a diverse range of aesthetic positions not merely as stylistic options but as trenchantly argued ethical choices. Debates raged between those who saw a return to figurative painting and expressionism as an antidote to the cool cerebral conceptualism of the 1970s, and those who embraced postmodern and postcolonial theory as a challenge to existing formalist positions and nationalist narratives. As the pre-eminence of landscape painting in Australian art came under increasing pressure by artists and designers informed by popular culture, urban contexts and subcultural style, artists began to develop local responses and crossovers between art, music and design informed by increasingly international fields of reference.”

A 2-minute selection of the exhibits at “Mixtape 1980s” can be seen at the website for the Australian Broadcasting Cooperation (ABC) 1. The artwork is displayed to the accompaniment of “Everything’s on Fire” by Hunters and Collectors, the Australian rock group whose music fused pub rock and art-funk 2.

Fusion invited the noted Australian artist Scot Cotterell to review this exhibition for what the editors hope will be a regular review section of the journal in future issues.

Fusion and Appropriation: Dynamism and Flux

Review by Scot Cotterell

Appropriation art is not new to me by any means, it is the work I make but I must admit that to a certain extent I was ignorant of the depth of Australian appropriation-based art during the 1980’s. I was born in 1979. During my Masters of Fine Art research at the University of Tasmania I reconsidered the appropriative urge of 60’s Pop and Minimalist art practice and its relevance today, by looking at artists working now, in the post-net era. I imagine that in some ways some of my observations may appear naïve to those well versed in this era of Australian Contemporary Art production, but I also imagine that from the synthesis of my reading now in 2013, some interesting observations may occur. And despite this initial caveat, my working process as an artist is deeply engaged with fusion and appropriation as a methodology and hence my position here writing this review. This vast exhibition was an invigorating experience for me to consider the dynamism and flux in the work of Australian artists at the time. Some names were familiar, others not, some I recognised as laying seeds for the scene I leapt into as a young artist, others were discoveries that I took away excitedly.

This is quite simply, an epic exhibition. I have not addressed all the 120 works and have barely done justice to the works I have addressed. I was able to spend the better part of two days with the exhibition. This show as a whole is a highly designed thing, the angularity of the galleries combined with the exhibition furniture, panel configuration, paint colours and the work to create an immediately strong visual and spatial effect. As I enter, seven raw wooden cubes housing televisions play sections from the hit Australian pop music TV show Countdown, juxtaposed with a brutally decorative Leigh Bowery costume The Metropolitan, pith helmeted and gloved on a lurid lime plinth. The oversaturated Countdown footage evokes a kind of retro-futurist, global parochial dichotomy. Joan Jett, the Ramones, Culture Club rub shoulders with INXS and Split Enz.

Leigh Bowery

Leigh Bowery

Australian 1961–1994, worked in England 1981–94

The Metropolitan

c.1988

cotton, rayon, leather, sequins, metal, paint

(a) 184.0 cm (centre back) 67.0 cm (sleeve length) (dress) (b) 125.0 cm (centre back) 77.0 cm (waist, flat) (outer petticoat) (c) 125.0 cm (centre back) 112.0 cm (waist, flat) (inner petticoat) (d) 109.0 x 8.0 cm irreg. (belt) (e) 50.0 x 8.0 cm (neck belt) (f-g) 21.0 x 12.0 cm irreg. (each) (gloves) (h) 91.0 cm (outer circumference) 19.0 cm (height) 23.5 cm (width) (helmet) (i-j) 24.0 cm (height) (each) 12.0 cm (width) (each) 26.0 cm (length) (each) (shoes)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1999

© Leigh Bowery Estate

The entry unfolds into an angular vista of charcoal and blue walls, era appropriate mannequins confront me in two groups, one staggered up the left wall and a group advancing in formation to the right. To the left wall Peter Tully’s Urban Tribal Wear, an amalgam of art, craft, gay politics and fashion evokes a regional punk influence infused with references to the vulgarity of Australiana. To the right outfits by Katie Pye, Susan Norrie and Jenny Bannister stand proudly studded and fluoro, accompanied by an exquisitely punk screen-print Eighteen Tragic Martyrs by Gavin Brown in which Elvis, Beethoven, Hitler, and Lenin hover in purple aloft a lemon background, augmented by a dizzy array of collaged elements.

Lesley Dumbrell’s 1982 painting November resonates with a furtive angular abstraction, subtle colour shifts in the blue body of the work creates subtle ocular effects. The meticulously rendered lines evoke scratches, highways and maps, they suggest a constant start stop movement occurring in all directions at once. On the opposite entrance wall is a large Rosalynd Piggott work, Tattoo in which stands an elongated nude, arms in the air,

body covered in hearts in various forms. A cluster of black and white photographs, Bill Henson’s photographs of crowds of people in public spaces around the world, a perfect confluence of the general and the specific. Another lime plinth holds Marc Newsons LC2 Lockheed Chaise Lounge, fluid design meets an Australian Shed aesthetic via the polished, hammered and riveted sections that make up this gleamingly curvaceous object. A massive 1981 Dale Frank graphite on paper work the appealing eyes of the blacksmith facing the tyrant in which nebulous lines evoke a torrent of sweeping change, waves of intersecting graphite with an automatist edge begs for interpretive projection from me.

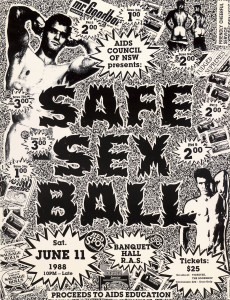

Graphic Design, Queer politics and the AIDS epidemic are brought to the fore in David McDiarmid’s posters for the Sydney Gay Mardi Gras 1986 and the Safe Sex Ball 1988. Juan Davila’s God and Country mashes Australian icons, art history terminology and Indigenous imagery all competing for visual dominance, pinned to the page by the word “wog”, which invariably overrides the other pictorial elements it suggests a prevalent racist facade that permeated and overrode other cultural elements in Australia at the time.

David McDiarmid

Australian 1952–1995, worked in United States 1979–87

Safe sex ball June 11 1988

1988

offset lithograph

62.1 x 48.1 cm (image) 65.2 x 50.8 cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift from the Estate of David McDiarmid, 1998

© David McDiarmid/Administered by VISCOPY, Sydney

Nearby 3 of Tracey Moffatt’s Something More Series (#’s 1,6,8) sing with their vibrant reds, chromes and yellows. The fragments of a tale that include stock-whips, boots, motorcycles, Chinamen and Oz white trash. The narrative holes left unfilled in this display may be filled, to a certain extent by the inclusion of Moffat’s film Night Cries: A rural tragedy (1989) 3, as we cut to a Lynchian scene of Jimmy Little crooning against a depthless black void. Night Cries tells the story of a relationship between an elderly white mother, not long for this world and her mature Aboriginal daughter. A sombre and well crafted soundtrack suspends the visual disbelief of this clearly staged, set, the washed out video transfer and lack of crisp edges, give the work an analog warmth, bringing forth the memory of the VHS camera.

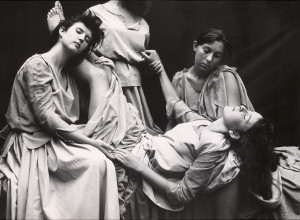

A streaking, stuttering, tri-panel charcoal work on paper by Bernard Sachs Fathers and Sons/Old Men and Young, uses as its inspiration photojournalism of the Iran-Iraq war. A series of vertical and horizontal cuts evoke the endless roll of a television with a de-tuned vertical hold. A cascade of brutally distant cathode ray chaos. The legitimacy and construction of media images and the documentation of war as propaganda are all here. Julie Rrap’s photographic work analyses the constructed nature of the female body, coloured photographic prints collaged together depict the artist via a Christ metaphor, my gaze staggering over the cuts in the individual fragments that make up the image. Anne Ferran’s Scenes on the death of nature 3 deals with female depiction in classicism in a chromatic reclining soliloquy. Feran explores how notions of womanhood have been coded in art. Anne Zahalka’s The surfers and The Bathers is an investigation into the mythology of Sydney’s Bondi beach through staged photography that explores the stereotyped characters of Oz beach culture. The painted backdrop with its visible wrinkles and edges adds to the staged quality of these awkwardly detached pictures. They hover in a kind of temporal nostalgia.

Anne Ferran

born Australia 1949

Scenes on the death of nature, III

(1986)

gelatin silver photograph

112.6 x 152.4 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1991

© Anne Ferran

This room opens out into a large white pristine space, severed by an angular charcoal wall, where I am surrounded by large paintings. Dale Hickey’s Pal and Pilchards, formal black rectangles depict machine parts and the industrial manufacturing of food goods. Cans labelled Pal, Pilchards, Spaghetti and Baked beans. There is a sparse but effective pictorialism to it, a large crank handle in the bottom half of the centre panel begs to be turned, thus cranking out another can of something.

Gordon Bennett’s Perpetual Motion Machine is a divided canvas. A vanishing background of crosses and housing commission suburbia with a newton’s cradle made of anglo-saxon heads swinging, eradicating indigenous culture in the form of ceremonial poles.

Tony Clark’s work is two small landscape paintings executed in the neo-classical manner of Nicolas Poussin or Claude Lorrain and a black on white architectural outline from above. Clark is interested in the disputes between high and low art, classicism and popular culture – as a counterpoint to often lofty claims which heralded the so called ‘return-to painting’ in the early 80’s. An impeccably groomed barber with a look of evil in his eye pauses mid cut in Geoff Lowe’s Deception: the man from ironbark. This could be as banal as a shave, or as spectacular as a decapitation, the violence suggested in this picture is palpable.

John Brack’s The hands and the faces, depicts an array of postcard reproductions of faces representing ancient cultures from across the world, in the centre, an Indigenous Australian spirit, raising the need for this ancient culture to be revered with the same respect as those exotic others depicted.

Six beautifully grotesque Peter Booth drawings thick with graphite and black chalk face a doorway to one of NGV’s characteristic elevated walkways. Early Gareth Sansom drawings to my left showing his trademark psychedelic chaos. A cluster of fifteen Scott Redford drawings, coloured pencil stamped with the artists’ name unceremoniously on completion, Jon Cattapan and Jan Nelson drawings and Victor Majzner’s Judges end this segue which address the studio, the brush, the VCA connection and its importance to Melbourne’s art practices at the time.

In the next space, the angular complexity of the first few spaces refreshingly dissolves away into a much airier, lighter space. A long Mike Parr self portrait adorns the left wall with a warped charcoal existentialism. Linguistic works are prevalent here. Language itself, the language of the self, and the language of images are explored with Robert MacPherson’s 20 Frog Poems, Narelle Jeblin’s Trade delivers people #2, and one of Robert Hunter’s deceptively complex white paintings. The far wall is dominated by Paul Johnson’s Fish House, a papier mache and encaustic wall piece that subtly alerts to me to a lack of sculptural works I hadn’t fully perceived until that point, a lack that never completely resolves for me throughout the exhibition.

A large trestle formation in the space holds acrylic topped display cases, made of raw pine and housing an amazing array of art, fashion and music publications of the time. Largely DIY, critically engaged and innovative in their scope and design, neatly installed, with attached descriptive sheets. Each case with its scanned total contents cycling through on an iPad in each case. Here the designed aspects of the exhibition shine quietly. Pneumatic Drill, Praxis, Art & Text, Things and Fast Forward, the innovative cassette magazine give a great chronologic splash of the self-publishing activities of the time. This is echoed and amplified in the screen space; a row of monitors embedded in a pine wall play catwalk excerpts from the Fashion Design Council of Australia’s important contributions, the seminal Australian Film Dogs in Space (Richard Lowenstein, 1986) 4 alongside the more recently produced Were livin’ on dog food! documentary which describes the Melbourne little band scene erupting out of the avant-garde audio experiments of the day. This room is topped off with screen works by Jill Orr and Lyndal Jones. This is augmented by another display case containing little-band posters, paraphernalia and records by Essendon Airport, Tsk Tsk Tsk, David Chesworth et al. The treatment of ephemera in this exhibition is meaningfully comprehensive.

This opens out to another space, having not yet encountered the work of Mike Brown, Maria Kozic and Jeff Gibson this small room holds the most new treasure for me, Brown’s wavering hyper-fuzz painting Manifestations suggests myriad pictorial elements that succeed in never fully coming into being, hung across the doorway from Maria Kozic’s Head (wall) a minimalist-pop masterwork concretely depicts the exploding head of an unknown character, hovering above in glorious rows of shiny black is another Kozic The Birds, a physical manifestation of the media-reproductive urge.

Mike Brown

Australia 1938–97

Manifestations

1982

synthetic polymer on canvas

182.8 x 243.8 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of Marc Besen, Governor, 1984

© Estate of the artist

Jeff Gibson’s Swindler, Impostor, Charlatan, … eloquently mixes the artist persona, the headline, the blurb and the self-portrait in proper larrikin style, addressing us as image consumers. The reproductive crux of this space is segued to the next by Vivienne Shark Lewitt’s Untitled #1-5 suite of soft-ground etchings.

A large black on white Howard Arkley painting Tattooed Head blurs my vision with it furry airbrush lines as I enter the last space, a large and impressive Imants Tillers grid painting Quest 1: The speaker which appropriates elements of New Zealand painter Colin McCahon echoes the ephemera displayed nearby. Jenny Watson’s The Crimean Wars: Cinderella adds a frenzied wandering spirit to the room. The main figure walks, shoes in hand, dazed by a bright light from above in a torrent of multi-colour scribbles. Over my shoulder Juan Davila’s classic Ratman leers at me with both quotational and technical bravado.

Jenny Watson

Australian born 1951

The Crimean Wars: Cinderella

1985

oil, synthetic polymer paint and gouache on canvas

240.0 x 175.3 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented through the NGV Foundation by Shell Australia Limited, Honorary Life Benefactor, 2002

© Jenny Watson

Stieg Persson’s Romantic Painting, its raw canvas edges, black oil and gold leaf materialism offset beautifully against Richard Dunn’s Tools of coincidence small detailed diptychs in which the tools of measurement and construction are contrasted by geometric, abstract formations derived from them. Another major Arkley work Muzak Mural – Chair Tableau resonates on the wall, that same airbrush-furr that seems to blink as you watch it butts up against four awkwardly static minimal chairs adorned with symbols derived from their own forms, squares, triangles, crosses and stars. The toffee-coated slickness of this directly gives way to wall of John Nixon’s cross and line works bold and unfinished, red, black and white, makeshift and resolute. Peter Tyndall’s A person looks at a work of art… overlooks this room, looks at us, while we look at it, as I approach the doorway in this ‘final’ space, I realise that this is another possible entrance to the exhibition and that this opening up the space to multiple possible physical pathways adds greatly to the exhibition design.

On either side of this doorway, and echoing a strategy used at other threshold points in the exhibition, Linda Marrinon’s In memory of little puss with its unfinished spontaneous edge sits with Rodney Rooney’s The setting sun which mixes the clean lines of magazines and armed services advertisements re-shuffled into new configurations. Located on another large lime plinth at my exit point a final ocular shudder is provided by Lounge Suite in steel and cooper by Biltmoderne. Triangles, mesh, cables and sinuous curves combine with pattern-heavy fabric design in this representative piece of nightclub inspired design.

Max Delaney, senior curator of contemporary art at NGV should be commended for the curation, layout and execution of an exhibition with incredible depth, and layers. The transition from space to space enacts the ‘passing through’, for each viewer, of an optimistic and challenging generation of artists, musicians and designers across that decade. Production methods, practices, genres, cultures and identities both collective and individual are all

questioned in these works and their collective arrangement in this exhibition resonates an intense energy that is testament to both the works and their exhibition. The layout and design of the exhibition mirrors this same energy as it traverses across the five exhibition spaces. The screen space, use of tablet devices to augment the information in the exhibition works and the presentation of historical ephemera in such a sympathetic way all add greatly to the experience.

About the reviewer

Scot Cotterell holds an MFA from the University of Tasmania School of Art. Scot is a nationally renowned young inter-disciplinary artist known for his works concerned with the experience of mediated environments. His work uses mixtures of sound, video, images and objects in gallery and live contexts to create experiences that reflect upon cultural phenomena. Scot was nominated for the Qantas Foundation Contemporary Arts Award and The Alice Springs Art Prize and awarded the Shotgun 2010 commission by Detached Cultural Foundation and CAST, a Sound Travellers national touring grant, and several state and national funding opportunities through the Australia Council for the Arts and Arts Tasmania including projects in the Netherlands, Germany and Spain. Scot has also received the Jim Bacon Foundation Honours Scholarship, and Australian Post-Graduate Award Scholarship and a Gordon Darling Foundation professional development grant. Cotterell’s work has been performed and exhibited nationally and internationally.

www.scotcotterell.com