Simple Models Create Steep Learning Curves in Academic Design Studio

Authors:

Peter Lundsgaard Hansen, University of Copenhagen

Torben Dam, University of Copenhagen

Virginie Le Goffic, University of Copenhagen

Ellen Braaeis, University of Copenhagen

Abstract

This paper presents an easily adaptable, very learning-efficient and solution-oriented design studio method: ‘the simple model method’. On a practical level it solves well known problems that occur when teaching design studios. On a theoretical level it suggests a ‘third way’ of bridging design theory positions normally regarded as mutually incompatible. The method is the result of years of ‘trial and error’ design studio teaching at the University of Copenhagen, triangulated with academic design theory research.

Research based design studio teaching poses a fundamental pedagogical challenge, as it must combine skill-based design practice with academic-explicated theories and methods. The vehicle in the development of the simple model method is overcoming the challenge of ensuring that a group of students with various backgrounds and cultures can produce specific and consistent design proposals within a limited time period. While simultaneously providing them with an overall understanding of, and tools to handle the design process. The simple model method provides a physical platform to facilitate the exchange of ideas and experience through seeing, for both individuals and groups of students, their supervisors and other actors. The simple model is a non-verbal agent. However, due to its simplicity it enables verbalization supporting a solution-focused design studio teaching strategy.

The simple model method is presented through a specific design studio course undertaken at the University of Copenhagen and is discussed according to staged, systematic design process thinking on the one hand, and wicked-problem thinking on the other. Reflections on the possible theoretical contexts of the interactive use of the simple model method throughout the design process suggest a possible theoretical ‘third way’, acknowledging both the staged design process as well as the wicked problem/solution entangled nature of the design process. In a pedagogical perspective the simple model method has the capacity to bridge theory with practice. The iterative use of the method in combination with its physical, spatial appearance helps the students work with and understand design as both a product and a process.

Keywords

The Simple Model Method, Landscape Architecture, Studio, Design Teaching, Design Process, Wicked-problem

To cite this article

Hansen, Peter Lundsgaard, et al. “Simple Models Create Steep Learning Curves in Academic Design Studio.” Fusion Journal, no. 3, 2014.

Introduction

In education, learning is often referred to as knowledge deposited into human containers. However, learning about design and design thinking presents different pedagogical challenges. The core of design is to resolve ill-defined problems, adopt solution-focused strategies, employ abductive thinking, and use non-verbal, graphic/spatial modelling media to explore wicked problems (Cross, 2007: 38). The situations studied are often more complex than any one person or discipline can comprehend. From a design educational perspective, the question is how to find a way of handling this complexity, where the frustrations inherent in design thinking do not confuse the students and hinder practical design progression. How can we as teachers structure a design studio in a way that enables students who are building up design experience, to learn, improve and elaborate their design skills?

Studies of design try to understand the design ability based on reports from designers and observations of designers at work, experimental studies and theorising on the nature of design ability (Cross, 2007: 35). Some scholars like landscape architect and planner Carl Steinitz have discussed building up experience, and distinguish between the anticipatory approach and the explorative approach as two paths into a design, where “one skips back and forth between these extremes” (Steinitz, 2011: 4). Steinitz himself prefers the explorative and inductive approach. While he supports the explorative approach through survey and analysis in small leaps forward, the French landscape architect, Bernard Lassus lets the design guide the gathering of information. The procedural theories present the structured and staged process with systematic research, analysis and creative synthesis as opposed to ‘creative risk taking’ (Swaffield, 2002:33).

Even though the staged, systematic design belongs to the 1960s and “creative risk taking” originated in the 1980s as proponents of a staged, systematic process, they are still widely used. This puts educational programs in a position where theories that can oppose one another in academic design thinking, can co-exist well in the practical design process. In the international Landscape Architecture program at the University of Copenhagen we encourage students to move back and forth between different procedural theories, and to blend and adapt correspondingly to design problems, teaching, and personal preferences. Thus the educational challenge in question is not to make the students believe in one specific procedural theory, but rather to teach the students how to make conscious decisions in a whole array of theories, whilst improving and elaborating their practical skills in a design studio. At the LA programme at the University of Copenhagen we have developed a simple model method that works as an agent for creative consciousness, helping the students navigate more confidently in the design process.

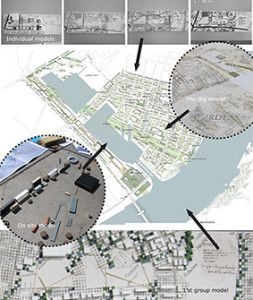

The objective of this paper is to contribute to teaching design studios. We aim to discuss the challenges of learning design in academia with large numbers of students from different landscape architectural programs working in groups in an intense design course period. The paper focuses on a single case – a well documented design studio, where the simple model method has been used several times with various purposes throughout the studio, enabling conscious artistic decisions. The simple model method aims to provide a platform for students, supervisors and other involved actors for the exchange of ideas and experience – individually and in groups – and for a solution-focusing strategy (ill. 0). Lastly, the simple model method facilitates the key pedagogical aim of teaching design studios: to increase the student’s ability to translate physical form (the simple model being a non-verbal agent) into a spoken language (creating an explicit awareness).

Illustration 0. The model box then it is in use. ©

Illustration 0. The model box then it is in use. ©

Case Method and Theory

The paper presents and evaluates the simple model method in a design studio with 2nd year master degree students attending the Landscape Architecture program at the University of Copenhagen. We describe the process of the studio and follow the work of one group consisting of five members. The group in question provides us with a general impression of all groups. The nine week course in Landscape Design was held from April to June 2011 and was attended by 60 students. Among the students, 25 bachelors came from the University of Copenhagen and 35 from other universities, from Europe, Australia and North America. After a few days of individual work with simple models, the students were divided into 12 groups.

The project site was deliberately chosen far away from Copenhagen, supporting the idea of an exploratory approach, and giving equal conditions for all students. The site was the harbour dock area in Bordeaux (France), which at that time was undergoing a planning process managed by the Greater Bordeaux Area Council (CUB). The harbour dock has two large basins protected from the Garonne River’s tide, accessible to large vessels and ocean-going ships. The dock area formerly hosted industry, warehouses, a submarine base from WWII and a shipyard. Today, the dry docks, a submarine base and some warehouses still remain. In 2011, CUB stipulated the planning of new neighbourhoods, institutions, a new road and a third bridge crossing Garonne River, in order to improve the infrastructure of Greater Bordeaux. The bridge, the first phase of this planning operation, was under construction at the time of the studio.

The studio resulted in a project submission and an examination. The studio started with simple models followed by a final model prior to the final submission and examination. At the examination, a large contextual model made to support and test the smaller models was situated in the centre of the room. It was put in front of the final design proposal. Each group presented their work together as a team, followed by an individual examination before grades and evaluations were given.

Illustration 1. Phases. The diagram shows the simple models in connection to hand-in. Although the models made from using the model box are used more intensely when we travel they are also used in the studio. ©

Illustration 1. Phases. The diagram shows the simple models in connection to hand-in. Although the models made from using the model box are used more intensely when we travel they are also used in the studio. ©

The purpose of the simple model method is to identify, formulate and resolve problems and solutions throughout a design process. The method employs two kinds of models (ill.0 &2). One type of model is a model box with different materials. This type is used when we travel and when we have supervision in the studio. The materials do not look like anything in particular and therefore this model is abstract. The second model is the base-model. This model fits into a larger context model and this model is repeatedly tested throughout the course whenever there is a hand-in and for the submission. Simple models express concepts, important components and the architectural language. The model is non-verbal, physical and spatial. The simplicity means that the student has to address key components, the architectural language and syntax. Working with the models is democratic in the sense that every student and supervisor can rearrange and rebuild collectively in an on-going dialogue but also without suffocating personal artistic expression and integrity. The ability to see and recognise spatial and structural quality becomes as important as being able to create. On the matter of seeing philosopher Thyssen says,

“It looks as if it is not at all possible to observe the world without prejudice (or reservations). If one is open beyond any conditions, one will not know where to turn ones attention. Everything weighs equally heavy, nothing can be left out or be forgotten, and all consciousness will drown in its own surfeit. So we protect ourselves from a too complex reality by simplifying – by choosing a theme, by distinguishing between central and peripheral, and by setting up a series of ‘holdings’ or ‘this is how we do it” […] “To simplify and thus to ignore is a condition for seeing.” (Thyssen, 2013: 9)

We compare Thyssen’s ‘’world’’ with a complex design situation and acknowledge the need to reduce this complexity. What we have observed in design studios is that simple models help make complex design more focused, and they make way for conscious leaps to other procedural theories when needed. Thus our approach aims to fulfil two objectives: it should both help qualify the design process, and address the design quality by way of seeing better.

Illustration 2. The base model. The base models fit into a larger context model. ©

Illustration 2. The base model. The base models fit into a larger context model. ©

There are however restrictions to free enterprise. In the studio we fixed the size and scale of the model base so it could fit into a larger model and be tested and documented with photos. An important pedagogical aspect of steering the studio is to have ceremonial events, exhibitions and presentations that create moments of reflection and constructive critique, and thus opportunities to connect the physical expressions with a spoken language. The repetition of making simple models over and over again throughout the studio and during the fieldtrip develops the students’ ability to make models anywhere, at any given moment and in all kinds of weather. Basically it is training in seeing specific qualities that can be transformed to the model media by means of simple materials rather than refined and manufactured elements. Simple models have the advantage of being an inclusive media; everyone can participate, which is not the case with another commonly used design media such as AutoCAD. The simple models don’t allow for superimpositions, which can happen when drawing with pencil where everyone can add a layer to the sketch until nothing is clear anymore. Besides being inclusive, no special communication skills are required to participate which keeps the group’s focus on the matter in hand, and the development of one specific version or solution.

The simple model is also used for analysing and documenting reference projects. All exemplary works of architecture studied while travelling are analysed and documented this way. Much like a pencil to paper the models become an extension of the hands that move the materials and create a distinct language between the students. This provides the students with self-confidence and motivation for the assignment, as they see that iconic projects are also founded on a spatial concept. So these analyses using the simple model method allow for a specific kind of knowledge transfer into their own design projects. These kinds of models allow the students to apply a spatial concept to the site, and to create a very readable synthesis.

We consider design as a prerequisite to the explorative phases in an iterative process. The iterative methodology is centred on continuously creating, testing, and redefining the problem until the problem formulation and the design proposal correspond to one another (Braae & Tietjen, 2010: 64-69). As a consequence of this method, students develop their projects and reformulate the problem while repeating the same model throughout the studio. This is a self-correcting process:

“Premises used in initial concept often proved, on subsequent investigation, to be partly or wholly fallacious, nevertheless, they provide a necessary starting point. The process can be viewed as inherently self-correcting, since later work tends to clarify and correct earlier work.” (Waldron & Waldron, 1988: 95-106).

This self-correcting process calls for tenacity and an ability to hang on to the initial idea. Design researcher and educator Nigel Cross refers to two opposite points of view. One is Marples (1960) who stresses the importance of using alternative opinions as a necessary step for exhaustively understanding the real nature of the problem. The other point of view is Rowe’s Design Thinking (1987), who observed from his case architectural studies, that many designers actually tend to work and develop one single solution in a field of a potential multitude of answers. Our method supports the idea of working with and testing the students’ initial idea and subsequently developing it into an elaborated design proposal. This helps the students to focus on an idea and explore its potential, rather than testing various kinds of solutions hoping that a great idea will turn up. In other words, the main aim of our design studio is to develop the student as a designer rather than develop the site through the design. In some cases though, the initial idea turns out to be inadequate and needs to be recreated, which is a natural and integral part of the self-correcting process.

The inclusion of simple models into our design studio is based on practical scholarly problems in the studio. Obstacles to learning design in academia with theoretical paradigms, combined with significant numbers of students, create limitations for reflection over a nine-week course. At the same time the learning environment should not abandon the students in the progress of obtaining design experience and skills. Unproductive moments with ‘fear of the white paper’ on the one hand, and on the other, the time consuming and often disoriented gathering of enormous amounts of information can be seen as un-reflected reactions to theories. Students’ focus on the genius and artful design might lead to ‘fear of the white paper’. And the ‘disoriented information gathering’ can result in a student getting stuck in survey and analysis believing that this in itself will lead to a creative solution. So how can scholars in a design studio guide landscape design students to a fruitful, time-efficient and productive design process, with adequate frustration (which is necessary), but without setting back the educational process, and yet motivating the search for new ways and elaborating design skills?

Both the staged, systematic design process and the wicked problem theory as Rittel and Webber define it, have their limitations. The wicked problem theory can be a relief and a comfort because nobody can be blamed when a problem is wicked. The staged design becomes unproductive when one realizes that “the information needed to understand the problem depends upon one’s idea for solving it. Problem understanding and problem resolution are concomitant to each other” (Rittel and Webber, 1973: 161). And the wicked problem theory may also play a role, suggesting it to be ‘abductive’. Then the student is stuck. The challenge of learning design in academia is the need to be familiar with the procedural theories as well as theories that address the complexity and the ill-defined problems in design. This is when the simple model method is useful. It rests on the idea of enhancing the ability to navigate consciously in the many procedural theories and the wicked problem theory. This degree of consciousness in the design process is necessary if one is to avoid roaming aimlessly from one theory to another, but knowing which one is productive for understanding the current challenges. Master students with some design experience respond positively to this way of working when invited into a solution-focusing, abductive process using a non-verbal media. The writer Donald Barthelme points out that, “Art is a process of dealing with not-knowing, a forcing of what and how” (in Swaffield, 2002: 60). Simple models help to overcome the students’ fear of the white paper by connecting ‘speech’ to ‘form’, and as soon as a model proposes a solution, the survey and the analysis can concentrate on the problems behind that solution and thus steer a smart collection of information.

A glimpse of the academic challenge can be identified within the existing procedural theories. Before the 1960’s, design had been described as a staged, systematic process, supporting a method following survey-analysis-design, SAD. The SAD model supports the idea of design progressing in linear stages – one leading to the other. This design process appears obvious and self-explanatory, however, it does not adequately reflect the situation that designers find themselves in today. The challenge is one of authorship and client. Kevin Lynch describes a “normal process” this way:

“In the most common case, a site plan is made by a professional for some paying client, who has the power to carry it out” […] “In a project of moderate size, site planning and the design of the buildings will be done simultaneously, preferably in a single office.” (Lynch, 1984: 2)

Today, designers more often work in multidisciplinary teams and in networks with many actors, including more than one client. Thus a site plan made by a single professional is not always the case and site planning is seldom done in a single office. If we accept that design activities have more than one author and that the actors have different theoretical backgrounds, then the aspect of “not-knowing” must be closer to the rule than to the exception. This calls for an adequate approach for handling more than one procedural theory in teaching since we still observe that students under time pressure tend to fall back on a single linear design process. This is a disadvantage when it reveals significant inadequacies in meeting the demands for a design solution.

In the 1960’s, Horst Rittel sought an alternative explanation to design in the general ‘Theory of Planning’, confronting the underlying premise of deductional thinking used by engineers and within natural sciences. Instead, he found design and planning problems influenced by hermeneutics’ wicked, ill-defined problems. The indefinable problem became an acknowledged issue for all, rather than one individual’s concern. By publishing the book RVSP Cycles (1970), Lawrence Halprin also contributed to a better understanding of the design process. He regarded it as a cyclical structure, revealing the interconnection of “Resources are what you have to work with.” […] He developed the idea of “scores which describe the process leading to the performance.” […] “Valuactions, which analyze the results of action and possible selectivity and decisions.[…] and “Performances which is the resultant of scores.” (in Swaffield, 2002: 45). Lynch (1984) focused on the hard work leading to a design solution rather than letting design remain a mystery and a flash of revelation; with a design solution things get clearer and a design proposal starts to appear. Krog (1983) points out that the process collapses when the “fearsome gap” between the functional diagram and design development occurs, and fear is apparently a part of the student’s hesitation. Rittel & Webber (1973) as well as other scholars (Cross, 2006; Høyer, 2008) touch upon the relationship between the specific and the generic; between information of the particular situation and knowledge on how to make design processes work. Rittel & Webber conclude the co-existence of problem formulation and problem solving hence dissolve the deductive SAD concept. Krog calls design “creative risk taking” and stresses that we must learn to tolerate “substantial personal terror and uncertainty”, he exaggerates the words to meet a probably frustrated landscape design student at eye level (in Swaffield, 2002: 58-59).

None of the current theories are able to support all the aspects and phases in a design process. In the design studio presented in this paper, both the staged design process and the intellectual process of gathering information, problem formulation and solution provide a backdrop for the task of teaching landscape design. The staged design thinking allows us to turn our attention toward specific parts of, and themes in the design process, whereas the intellectual exploration and conceptualization focuses on the result and the coherence in the design process. However, both must be subject to conscious critical reflection throughout the whole process in order to understand when to shift from one to another. We encourage students to adopt solution-focusing strategies, to employ abductive thinking, and to use non-verbal spatial media to make a common vocabulary amongst design actors by working with simple models.

How we teach

Mission impossible & individual models

On the first day of the course, each student receives identical physical model bases and is asked to hand in a simple concept model one and half days later. The assignment is broad; to develop a first draft for an urban transformation of the dock areas by any means that they think might fit. The title of this phase, Mission impossible, ironically refers to the movie of the same name, acknowledging the students’ situation. The model base is basically a digital map printed on a foam-plate shaped to fit into a large contextual model representing the greater Bordeaux area. The sixty individual models are presented at an exhibition open for both the students and the public. The ceremonial atmosphere of these small events – the handover of the model base and the exhibition of the concept model – has proved to be of significant pedagogical importance. Besides making it clear that we take the students’ work seriously, the students and the teachers have the opportunity to compare the models and to observe similarities and differences in both design strategy, modelling techniques and to support early procedural thinking based on the models.

The students are asked to acknowledge their fellows with a yellow and a green post-it note, commending the design idea and the model building technique and hence developing a spoken language on top of the non-verbal media.

Five individual models belonging to each member of a group is shown. The individual models are used to get acquainted with each other in the newly formed group and to foster the group’s first model. In this phase the wicked problem theory is used to ask for a solution rather than visual, experimental and verbal surveys and analysis. It is an attempt for a direct confrontation with a site more that 1200 kilometres away. The five students in this particular group use different model building techniques; they explore patterns from the map, draw lines, and reconstruct existing structures. Student A divides the docks following the two basins and the eastern quay. Student B reproduces a well-known building pattern. C concentrates on the bridge and the road structure. D is concerned by the coherence of the area; and E inscribes a cross, using directions interpreted from the map (ill. 3). Though different, the 5 concepts served as substantial demarcations for future surveys and analysis.

Illustration 3. Mission impossible. One and a half days after the course starts the student’s hand-in a concept model for the first exhibition. ©

Illustration 3. Mission impossible. One and a half days after the course starts the student’s hand-in a concept model for the first exhibition. ©

Mission possible & the first group model

One week later, the groups produce a first model, fitting it into the big model of the greater Bordeaux area as done with the individual models (ill. 4). For this phase, a set of requirements is added to the scheme: the group concepts should be accompanied by a title indicating the focus of the design, three main issues of focused strategies, a first visualization, a short text, and diagrams. Group models are exhibited again next to the individual models. The students have gathered information about the site from the Internet and inspiration from other exemplary landscape design references chosen by the students. In addition, the students study maps, drawings and site descriptions, adding a new layer to the project through a verbal research phase according to Sasaki “Verbal research means reading and discussing” (1950). By collecting general information and by using the big model, the students are relating the impact of their idea to e.g. context, infrastructure, and network.

Illustration 4. Presentation. ©

Illustration 4. Presentation. ©

The group represented in this paper combines a concept with a grid of parallel lines originating from existing built structures, which extends from the surroundings into the site, and to where the roads meet the edges of the docks. The space between the scattered patches of grid is proposed as a network of green structures. The questions of what these networks are and how they work are still open. The group model presented at the exhibition and the following discussions, point to a study of the potential consequences of the relationship between the green structure and what looks like a dense urban fabric. The group now turns towards a short phase of staged design where each student zooms into different areas of the model for a closer study. This phase encourages both artistic and functional modifications to the group model.

Fieldtrip as a combination of experimental research and design

The students visit the project site for the first time during a fieldtrip to Bordeaux two weeks after the course starts and after completing the first group model. The programme for the fieldtrip entails research into a range of exemplary reference works, surveys of the site and of the context of Bordeaux. Prior to leaving, all groups prepare material for working on site. An important part of the preparation is to organize a model box (ill. 5) in order to make models while travelling. Studies are made of iconic landscape architectural references. They are projects selected by the teachers for their conceptual prototype value, and analysed for their spatial concepts using the model box. Attempts are then made to encompass parts and ideas from these references into the student’s own design.

Illustration 5. The model box. The students prepare their own model box for working on site. ©

Illustration 5. The model box. The students prepare their own model box for working on site. ©

Working on site allows the students to ‘sense’ the place, make notes, take pictures of materials for later reference, draw sketches, and analyse – individually and in groups. Group work consists of walks, talks, meetings and testing the group’s design idea through building models on site. A major vehicle in this part of the design process is the on-going collective building of simple site models. We ask the students to outline the idea of the site, representing it with basic materials from the model box. Although fixed scales are not possible, proportions matter to the extent that the simple models allow. The model forces the students to focus on the key components, and at the same time, working on site makes it clear that a small building, a row of old trees or certain materials used for ground cover can play a powerful role in their design strategy, although seemingly insignificant at first.

Meeting the students on site, we can see that they also use materials found on the site in their simple models schemes, which provide an additional tactile dimension to the models and to the understanding of this specific landscape (ill. 6). Chalk sketches and scratching the ground surface, combined with the models, makes it possible to make what Krog describes as a cartoonish testing ground; permitting description and dissection, encouraging evaluation and interpretation, and thus allowing research and experimentation to co-exist (Krog, 1983). A consequence of this phase in particular, is the difficulty of recording this process from a procedural point of view, since the students move to and from different ways of working and in short intervals. The dialogue within the group, and between the group and supervisor, are documented in notes and pictures for later use. The first hypothesis formulated through the models is tested, and the impact of their thoughts in 1:1 is imagined.

Illustration 6. Field work and meetings on site. ©

Illustration 6. Field work and meetings on site. ©

The existing structures, scales and volumes have a tremendous impact on the work. Working on site speeds up the gathering of relevant information, as the students can concentrate on what they see on site, and what they observe happening to the model when they start building it on site. They no longer rely on a general systematic procedure. Building simple models is helping them to evaluate, interpret and modify the spatial relationship of primary components, and to pick up on significant details of the site. The use of simple models and walking through the site, opens different aspects of new observations that the group now pursues; studying the existing urban environment led to a more detailed interpretation of more than one neighbourhood, whereas the early draft was a more uniform structure. Lastly the group started making a focused study of the character of the existing recreational green structures that influence their own idea.

The iterative process

Shortly after the fieldtrip, approximately 4 weeks after the studio start, the groups submit their first draft for a master plan on the basis of a second model (ill. 7). The requirements for this hand-in are similar with the previous. However, after learning from the fieldtrip, the students are ready to add digital drawings to their work. The translation of the model into a precise plan opens a lot of questions related to scale and the representation of components, the construction, surfaces, topography and plant material. The students are still on a ‘mission possible’ proceeding from the physical model. The leap forward is greater than the students expect and what the procedural theories indicate, even though the first edition of the plan may not contain it all. Again the wicked problem theory may explain that as the solution develops, the problem formulation becomes clearer.

Illustration 7. Mission possible. The draft for the final plan is a product from working with models from the base-model and the model box on site. Using the simple models alleviates the transition from more or less concrete ideas to drawings. ©

Illustration 7. Mission possible. The draft for the final plan is a product from working with models from the base-model and the model box on site. Using the simple models alleviates the transition from more or less concrete ideas to drawings. ©

The group concept is strong, but the process of translating it into a 2D plan confuses the idea. Now the grid becomes a monotonous housing structure with a weak landscape architectural strategy. Far from what the urban structure anticipated in the model (ill.7). The students are now in an iterative process – in a “back and forth” process – testing various design solutions. Developing the solution on a detailed level is seen as a way of ‘checking’ the overall concept and the group’s programmatic points that they formulated throughout the first phase, and since developed on site. However, the students often experience this phase as doubtful and difficult. They are in a design process according to Lawrence Halprins terminology going from ‘scores’ to the ‘performance’, and making ‘valuactions’. Impacts on their design coming from supervision, presentations and discussions in the group makes them change or adjust their design in relation to their initial ideas. This iterative process is on the one hand very productive, and on the other very decisive, as the design can take turns in new directions.

Mission completed – Towards a final design

After 6 weeks, the students are asked to present a draft for the final plan to a panel of supervisors and opponent groups made up of fellow students. The groups have one and a half weeks left before the final hand-in. This presentation makes use of full prints of the plan in an appropriate scale with a title, sections, diagrams, visualizations and text. The motto for the presentation is “the more you can produce and show us – the more feedback we can give you”. All models are put forward for this presentation and are tested in the big model (ill. 8). Parallel to the design work, gathering of information has continuously taken place. This part of the process is driven by the development of the increasingly precise plan. The drafts almost always reveal unresolved issues that need to be addressed in order to complete the work, and they often show up where drawings are unclear or where there is a lack of coherence between the information shown on the panels. This presentation is the last opportunity to remove obvious flaws and make the last adjustments before the final hand in.

Illustration 8. The big model is usually situated in the centre of the studio so everyone has easy access to test their base-models and to have meetings.©

Illustration 8. The big model is usually situated in the centre of the studio so everyone has easy access to test their base-models and to have meetings.©

In the case of the group, the title Les deux allées – un nouveau quartier à Bordeaux (The two alleys –a new neighbourhood in Bordeaux) indicates an urban landscape that has become the key to rediscovering the intentions expressed in the initial group model, fostered by a detailed survey of landscape elements and the character of existing neighbourhoods (ill. 9). A question such as the hierarchy of the chosen elements and their mutual aesthetics arises in this phase. One of the most difficult parts of the design process is to maintain clarity within a complex drawing, as one should still be able to read and understand the concept in the proposal. In practice, it is sometimes a question of turning off layers that you have worked hard to develop and thus not showing everything you know. The staged, systematic design does not help the students in this part of the design process, because it is not a linear process. The concept rules the layers and the details: do they fit in, or not?

Illustration 9. Mission completed. The studio submission consists of posters, models and a booklet. ©

Illustration 9. Mission completed. The studio submission consists of posters, models and a booklet. ©

In the case of the group, the title Les deux allées – un nouveau quartier à Bordeaux (The two alleys –a new neighbourhood in Bordeaux) indicates an urban landscape that has become the key to rediscovering the intentions expressed in the initial group model, fostered by a detailed survey of landscape elements and the character of existing neighbourhoods (ill. 9). A question such as the hierarchy of the chosen elements and their mutual aesthetics arises in this phase. One of the most difficult parts of the design process is to maintain clarity within a complex drawing, as one should still be able to read and understand the concept in the proposal. In practice, it is sometimes a question of turning off layers that you have worked hard to develop and thus not showing everything you know. The staged, systematic design does not help the students in this part of the design process, because it is not a linear process. The concept rules the layers and the details: do they fit in, or not?

The design studio presented, is one of many courses available in the landscape architecture programme at the University of Copenhagen. The studio is an advanced design course and the main aim is not to study procedural theories, for which we have courses that focus explicitly on theories and methods. Although knowledge of related theories and their methodological impact is important for the student in order to achieve both specific design results and generic design process knowledge within the time limitations of a nine-week course. However, combining a focus on theory with a focus on the design – and mastering the design process in practice, makes it difficult to draw the full advantages of applying theoretical studies to practical design work. We compensate by urging the students and their groups to elaborate on their ideas and readings in the simple models, the procedural theories benefit from the simple model. Methods such as the staged, systematic design gain from having a solution-focused model right from the start, and the conceptualization design approach reaches a kind of concept with simple models, which eliminate the ‘fear of the white paper’.

The design studio at LA-UC works similarly to other landscape architectural educations, but differs from other educational programs by using simple models in the early phase of the design process, and by repeating them throughout. We produce models in different scales, surveys and analyses, plans and details, diagrams and sections, visualizations, text and strategies for developmental phases. Like other programs we also adopt new technologies and their inherent possibilities. The experiments with developing the studio pedagogically help us recognize that a theoretical foundation cannot be found in any of the dominant design theories. However, seemingly opposing theories serve as anchor points for the design process when supported by the simple model method. Landscape architect Catherine Dee advocates a form-based approach to design even though landscapes are in flux:

“Though landscapes change, the conception of relatively permanent structures to support human dwelling is required” and she stresses that “physical form, idea, utility and nature process are conceived as one” and this requires “a sculptor’s eye” (Dee, 2012: 8).

Simple models train us to see and to address what we see. So when the students put the idea into practice by building simple models, they create a special situation, however shortly, that connects vocal ‘speech’ and physical ‘form’. What happens in this time interval is crucial from a pedagogical point of view, since this is where the students are all connected to the design at the same time. When the building of the model stops, all that the students have left is the model itself, and the notes and pictures made in the process. The connection between what they say and the model is gone. With the simple model method we enable the pedagogical challenge of reading, interpretation and expression through a connection between ‘speech’ and ‘form’. The question of how to prolong or to document this connection better for later use is still open. The French sociologist Bruno Latour addresses the importance in “An introduction to Actor-Network-Theory” by saying that

“Social inertia and physical gravity might seem unconnected, but they need no longer be when a team of workers is building a wall of bricks: they part company again only after the wall is completed. But while the wall is being build, there is no doubt that they are connected” (Latour, 2005: 75).

Krog (1983) believes that we need; “more research and to engage in more experimentation”, “cartoonish thumbnail drawings which serve as a testing ground”, “to have an experience-supported reservoir of understanding” and believes that “we should visit places not just to see them with our snapshots, but rather to feel them. Let the seeing be documentary, but the feeling enlightening.” Simple models engage the students; the transparency of the design process within a group of students working on the same simple model while they talk about what they are doing is like making five people write with the same pencil at the same time successfully.

Conclusion

The simple model method is a reaction to a fundamental pedagogical challenge in our design studio. It seeks to bridge the practical and theoretical challenges we observe in our design studios and thus to combine skill-based design practice with academic design theories and methods. The case shows that the method has improved the design process in our studio as well as the design quality because; the students quickly and repeatedly get qualitative feedback from the simple models throughout the design; it maintains the focus on form, while at the same time enabling a verbalisation of reading, interpretation and expression of form-matters; it ensures that everyone can participate regardless of background and the case shows that the simple models can be used by one or more and provide the basis for a common understanding of the language used by the actors. Finally the method has generic qualities helping the students better understand the design process and the perspectives of having form concepts as driver for the whole process. The simple model method applies easily to other fields of landscape design due to its function as both an analytical and prescriptive media as demonstrated by the studies of works of landscape architectural references with the use of the simple model method. The repeated process is dynamic and even fun. The fear of the white paper and the exhausting gathering of information are reduced to a minimum and alleviated in our studio.

Acknowledgement

A special thanks to the students of the design studio in 2011 and to Rosemary Halsmith, Lasse Hansen, Marie Keraudren, Mai Saame and Nils Vejrum for the project Les deux allées – un nouveau quartier à Bordeaux.

References

Barthelme, Donald, (1997), Not Knowing: The Essays and Interviews of Donald Barthelme. Ed. Kim Herzinger.

Buchanan, Richard, (1992), “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking”, Design Issues, Vol. 8, No. 2, MIT Press.

Braae, Ellen & Anne Tietjen, (2010), “Constructing Sites on a Large Scale: Towards New Design (Education) Methods”, in Nordic Journal of Architectural Research, vol 1, pp. 64-71.

Cross, Nigel, (2006), Designerly Ways of Knowing, Springer- Verlag London Limited.

Dee, Cathrine, (2012), To design Landscapes – Art, Nature & Utility, Routledge -Taylor and Francis Group.

Halprin, Laurence, (1969), RVSP Cycles, Creative Processes in the Human Environment, G. Braziller.

Høyer Steen, (2008), Landskabskunst 2, Kunstakademiets Arkitektskole Forlag.

Krog, Steven, (1988), “Creative Risk Taking”, in Swaffield S, (2002), Theory in Landscape Architecture: A Reader, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lassus, Bernhard, (1998), “The obligation of intervention”, in Swaffield, (2002), Theory in Landscape Architecture: A Reader, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Latour, Bruno, (2005),”Objects help trace social connections only intermittently”, Reassembling the Social. An introduction to Actor-Network-Theory, Oxford University Press.

Lawson, Brian, (2006), How Designers Think: The Design Process demystified, Architectural Press, Elsevier.

Marples, (1960), The Decisions of Engineering Design, Institute of Engineering Design.

Rittel, Horst W.J. and Melvin M. Webber, (1973), Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, Policy Sciences 4, Elsevier.

Rowe P., (1987), Design Thinking, MIT Press.

Steinitz, Carl, (2011), Getting started, Teaching in a collaborative multidisciplinary framework, Wichmann.

Thyssen, Ole, (2013), Blik skift, Tre essays om filosofisk iagttagelse, Informations forlag.

Swaffield, Simon, (2002), Theory in Landscape Architecture: A Reader, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Waldron MB & Waldron KJ, “A time sequence study of a complex Mechanical System Design” in Cross, Nigel, (2007), Designerly Ways of Knowing, Birkenhäuser.

About the authors

Peter Lundsgaard Hansen, Landscape Architect and Associate Professor, Landscape Architecture and Planning, University of Copenhagen, 2010- . Responsible for 4th year design studio at the masters landscape architectural program since 2007. Peter has several years of practice experience, including his own office. Supervisor of more than 50 thesis’. plh@ign.ku.dk

Torben Dam Landscape Architect and Associate Professor, Landscape Architecture and Planning, University of Copenhagen, 1993- Teaches design studio on 3rd year bachelors landscape architectural program and 4th year master landscape architectural program, PhD supervisor and supervisor of more than 50 thesis’. Published book about design in 2007 and 2002. toda@ign.ku.dk

Virginie Le Goffic Lanscape Architect and research assistant, Landscape Architecture and Planning, University of Copenhagen, 2012-. Landscape Architect DPLG Verseailles 2000, Virginie Le Goffic has professional practice from the offices Jeppe Aagaard Andersen, Juul & Frost, FrodeBirk Nielsen / SWECO, and received several design awards in architectural competitions. Supervisor on bachelor- and master degree courses. vlgo@ign.ku.dk

Ellen Braaeis professor of landscape architecture theory and method. She is head of the MSc Landscape Architecture studies and head of the research group ‘Landscape Architecture and –Urbanism’. Ellen is trained as an architect and landscape architect from the Aarhus School of Architecture, where she also got her PhD. Ellen has several years of practice experience, including her own office. Furthermore, she is member of the National Independent Research Council for Culture and Communication. embra@ign.ku.dk