Fire doors in their eyes

Author: Neill Overton, Charles Sturt University

To cite this article

Overton, Neill. “Fire Doors in their Eyes.” Fusion Journal, no. 4, 2014.

A fire door is a curious portent of something anticipating a dark future. It is there to be closed. In the event of fire, it is to limit the spread of flame and smoke. We somehow remain unaware of its design until its function is brought into play. We rely both on its inactivity, and its presence. The fire extinguisher is another cypher of mortality affixed to a wall, the perpetual eunuch on guard at the door of the tomb. The aesthetics of “the gallery” as unopened crypt, as the quiet church of art, indelibly enshrines its purpose.

The gallery is imprinted with this inherited bloodline characteristic of its function, and yet it no longer serves this former role as museum of dead art. It is now subject to other directives of light, of noise, movement, music, café culture… it exists as a competing entertainment with the laser gun theme park. Professor Steve Connor, of the University of London, argues that the “art gallery” marks out its territory for all the world like a wayward puppy, irrespective of the “value” culturally or economically of the items it showcases:

It is not what you put in a gallery that matters. Since an art gallery can surround any object with a sort of invisible force-field or glaze of “aestheticality”, it is whether or not it stays in its place. I think it is in part this power of sealing or marooning things in their visibility and this gallergy to things that spread that makes art galleries so horribly fatiguing and inhuman: at least to me. (Connor 48-57)

Galleries, by dint of idiocy in their construction, impose architectures that systemically destroy the discursive one to one relationship with the artwork inside. The ideas raised here begin with thoughts put forward in a brief essay by Roland Barthes on a philosophy of “habitat” in his collection of writings in Mythologies in 1973, specifically in The Nautilus and the Drunken Boat. (Barthes 65-66) It reflected on the self-contained world of the submarine; piloted by Captain Nemo in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1869)where everything outside comes to him through the one glass-eye of a vast porthole.

It plunges us into all the myriad ambiguities of inside and outside worlds, and semiotics of windows, from which there are tunnels to many other hidden parallels. In many ways train carriages feature in crime stories of the 1900s in exactly this manner – as self-contained microcosm where people from different walks of life are thrown together. Outside, the world whirls by as a clanking, ever-changing vista of landscape flickering past in tune to the rattling of the wheels. The art gallery’s micro-verse is in this very jostling for position in history that Marinetti sought to overthrow as a false premise. We construct architectural spaces for their intimate restrictions: intimacy, and its opposite pole of public space.

Roland Barthes’s conjectures on habitat, and how we navigate through the spaces we use, became valuable philosophical springboards to considering the metaphors of “navigation” and “travel” that have insinuated themselves into the virtual spaces of the computer. The voyages of Captain Nemo in 1869 aboard his submarine Nautilus in Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (figure 1) remind us that nothing is fixed in time; whether “gallery space” or “virtual space” or the here and there of private rooms as command modules with everything required to support existence “at hand”. If the computer is this era’s Nautilus, it demands of us to frame a philosophy regarding the current expectations that everything comes to us, in the screen, not outward from us. (Overton, 2003.)

Figure 1. Captain Nemo aboard the Nautilus, In Jules Verne’s “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” 1865, Pierre-Jules Hetzel pub., 1871 ed., illustration copyright Alphonse de Neuville

The fact that “Nemo” means “nobody” in Latin, and “omen” backwards was not unconsidered on Jules Verne’s part in 1869 when the book was first published…Today it echoes the tabula rasa that the “shipping container” approach to “art gallery” architecture deposits us in… we are in the space of nobody, and nowhere. In finding submarine equivalence, it lies in the insular environment that the art gallery once sought… to create an immersive, cordoned off environs in which to slow the viewer down to the time of the artworks themselves… to the half hour spent in contemplation of a Turner painting. We spend time in front of the landscape we walk through; the bush, the rock hills, the sea and its half revealed octopus. The painter’s task is to ease us towards spending the same amount of time in contemplating their simulated canvas version of the landscape as we might spend in front of the scene itself. Lloyd Rees spoke of the contemplation to be found equally in both cathedrals, and rock hills in nature. He posited ideas regarding place and space needing to be engaged as resonators of thought. Rees found this in common to both the untidy, rock-strewn landscapes of the Olgas, and in the brooding interiors of cathedrals, in particular in his Cathedral of Chartres drawings in France from 1973.

Figure 2: Lloyd Rees “Dusk in the transept 1” 1973 oil on canvas. University of Sydney collection. Copyright Lloyd Rees.

In regarding the Australian landscape as a meditative encounter, laden with spiritual significance, and needing to be entered contemplatively, Lloyd Rees returned to these twin subjects doggedly over successive decades. He drew and painted the jutting cliff-faces from the front window of his son’s house at Sandy Bay overlooking the River Derwent. Outside and inside space melt like butter into his conscious drawing towards monumentality. Both are primal touchstones towards a higher level of consciousness; as spiritual places. (Rees11) One, of immediate immersion in the natural world, its shelves of rust brown, heaped earth and boulders, awkwardly stacked. The other, a man-made tower pointing its finger to the sky… mathematical in its geometry and precision, and aligned with the coloured eyes of stained glass windows in tapered arches of light to the outside world beyond. The function of the “art gallery” was initially as a similar conduit towards contemplation; it sought to isolate objects and ideas towards a deliberate, selected scrutiny. It privileges them for a different consideration than we might normally give them in the world outside the gallery. Yet overwhelmingly in the 21st century, the “art gallery” chews gum, talks and texts all at the same time; it panders for your misdirected attentions. It no longer knows if it shops or prays. At once entertainment centre, shop, market stall of the unsaleable and boutique of design. The building is an atheist that no longer believes in art.

Our evolving, multi-purpose public buildings no longer advocate singular or clear purpose. The library as learning commons is increasingly screen-driven, including audio, café, internet café, and leisure centre. Contemplation in quietude, as Rees advocated as a precondition of art in the land and in our monolithic or “collective” buildings… is bumped further down the list of our expectations, as we casually position it and the “art gallery” alongside the turnstile of the supermarket in our society’s pattern of usage.

In film lore, the use of restricted space as a concise theatre of events finds form as early as Submarine (1928), through to the type of constricted palette Alfred Hitchcock sought in Lifeboat (1943), Rope (1948) through to the masterwork of “semiotics of windows”, and its narratives of viewing, Rear Window (1954). The last of these is a rumination on the reciprocal traffic of viewer and the viewed, and our shifting roles as both participant and protagonist. Lifeboat (1943) is a grim war-time piece of survivors of a torpedoed ship. In films of this ilk, the confined space acts as protagonist of the works and actions within it. Other genres including The Lady Vanishes (1938), or Stagecoach (1939), or Das Boot (1981) offer confined spaces of train carriages, or inside a stagecoach, ships or submarines to place opposing people and views into close, clashing juxtaposition. It holds them up to the light of this precise, unrelenting gaze. The gallery is a similarly decisive, dominant architecture that orchestrates the art culture within its confines. It acts as venus flytrap for the casual observer, forced into call and response with rectangles nailed to walls, and the various other manifestations selected out by curators for closer inspection as “art”. Lifeboat is as lastingly depressing a film as you might ever watch… there are images within it that will cast a dark pall over the rest of your life. Their nightmare uncertainties are those of confined spaces that no longer diagnose their real purpose.

It is this reintroduction to the discourse of the core language of “form and function” in terms of evaluating the usability of the design that effectively underlines the point of what is lost when “the gallery” becomes the event. In forgetting its intended function, the gallery then installs those artworks that best suit its limitations. This is thus twofold: the deliberate modernist architecture that, like Federation Square in Melbourne, (opened in 2002) is a loud announcement of difference to other architectures around it – and trumpets itself as an “edgy” public space container of art – in both the adjacent Ian Potter Centre: National Gallery of Victoria, and the stone bee-hive of the Australian Centre of the Moving Image.

Figure 3: Australian Centre for the Moving Image, (ACMI), built in 2002, Federation Square, Melbourne.

Like toothy Luna Park in St Kilda, its entrance bat-signals itself as a theme park of postmodernism. The second type of gallery architecture being created is not as a self-conscious “art building” at all, but the opposite. Uncertain of its continuing singular purpose, it factors in a multi-purpose future. Teaching space? Offices? Library storehouse? Shop? Barn or medical centre? King Kong doors that can close off sections, from larger rooms to discrete venues, or open wide onto the road. All these flexible options are built in; it can be repurposed at any turn of the wheel. Like a real estate agent walking prospective corporate customers through its bright, empty coffers with talkative claims of “you can convert this to a dining area, and this can be offices, or even a garage.” Flexibility in and of itself can also be indecision made manifest.

The oxymoronic term “visual noise” readily applies to the art gallery environs. It refers to unintentional, distracting “noise” that jars or leads the viewer away from the works. It is anything visual that clutters or disturbs an unmediated reading of the work. The overly large gilt-edged frame that dominates the small painting within would be a traditional example of 19th and 20th century gallery practices over-dressing the art.Anything unintended that pulls against the clarity of meaning and of reading the art is unwanted “noise”. Like overloud talk-back radio blaring across the cafe, the alarms of beeping doors, heating, lights… it is everything that collectively denies purpose.

The communication theorists in Britain, John Morgan and Emeritus Professor of Fine Art at Leicester Polytechnic, Peter Welton, refer to this distorted traffic of “visual noise” as not only physical but semantic noise. In relation to this unintended architectural discordance their summary is:

Any striking or unusual aspect of a design can function as noise if it fails to reinforce the sender’s intention; the gimmick which you use to attract the attention of the passer-by may be all that is noticed, and come to be thought of as the message itself. (Morgan and Welton 15-33)

This dual concept of both physical noise and semantic noise has implications on how fragmenting we find the disconnect between the enveloping space wrapped around the “art”, and the static interference it raises to exhibition codes of image transmission and receipt.

The deliberations Gaston Bachelard directed towards how the spaces we use change us, or at least our views, considers this opposition between intimacy and imposition. He wrote, in relation to the house, from cellar to garret, the significance of the hut:

We must look first for centres of simplicity in houses with many rooms. For as Baudelaire said, in a palace, “there is no place for intimacy.” (Bachelard 29)

In a gallery designed as a relationship of “many rooms” rather than the omnipresent one white warehouse, it is even more important that the viewer/user of that space can navigate across it through clear sight lines and sound lines. We seek out the hut, the round house, the primitive epicentre that offers us sufficient intimacy and enclosure, so that we are not swamped by the cold, factory floor industrial monolith. Failing to find these, we traverse its walls and windows, led from room to room in perpetual “tour” of a space without centre.

Within the self-contained, self-referential submarine of the art gallery… the trench windows blend shards of shadows inside the white cell. The gallery as false theatre of the real, where inside/outside are constructed artifice. Everything is packaging. Everything is signage, ultimately referring to nothing beyond itself… a mirror reflecting another mirror.

Whoever wants to describe a window will do it well only if he also describes the view beyond, the view of which that window is, as it were, a framework…(Kotarbinski 1966: 514) (Sebeok and Margolis 110-139)

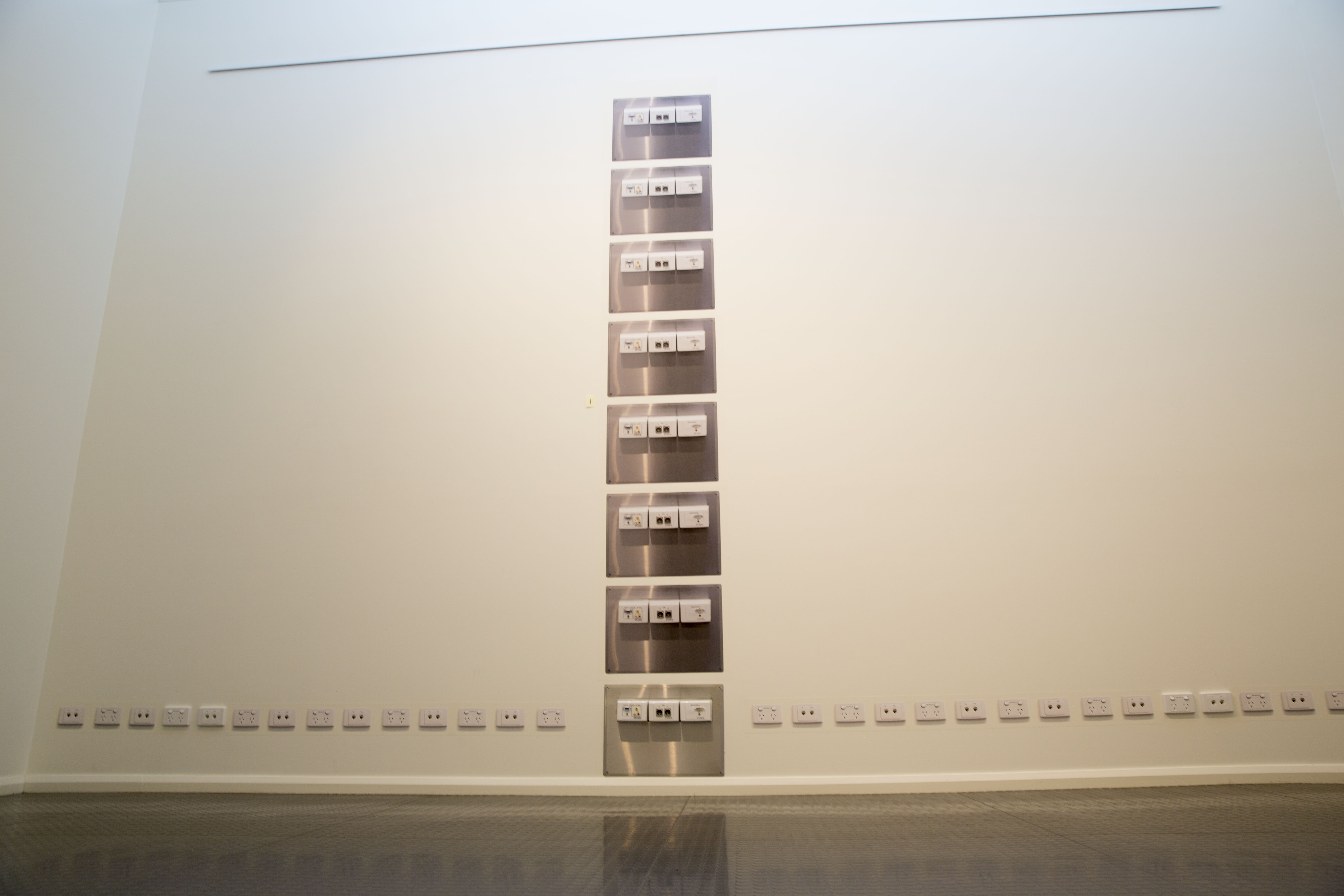

If the intention of windows is all eyes and light, and as a membrane between interior/exterior space… then gallery trench windows become a failure of function. Inevitably, all they do is leave tracks that rudely scar, and clutter, the pristine white face of the self-contained gallery, and its prior requirements of unimpeded running length of wall space. Now gallery interiors are routinely pocked by this flotsam of power panels, switches, cords, lights, signage, egress buttons, alarms, heating controls, sound controls, fire extinguishers. The design-felony that is perpetrated is to enact a fundamental confusion between interior and exterior space. What once were “spaces between” are now filled with interruptions; a glass jar crammed with black blowflies.

Figure 4: “Untitled” Digital photographs, hexachrome print on phototex, same scale of power panel fittings (repeated) and fire extinguisher in the Gallop Gallery, CSU, Wagga Wagga, 2013.

Figure 5: “Untitled” Digital photographs, hexachrome print on phototex, same-scale of power control panel fittings and fire extinguisher in the Gallop Gallery, CSU, 2013.

Galleries, at least since Duchamp, and the Dadaist cabaret-based vocal interventions – chart a history of architectures and interruptions. It is that wondrous moment when the dictates of the bricks and mortar building are subverted. As a schoolboy, at Camberwell Grammar School assembly, when the Headmaster – all leather elbow patches, burgundy Hymn Book and tweed – gave his 9.20am report on the School’s finances, it was that heady moment when a boy in the third row spontaneously vomited on the floor. The school gardener was quietly ushered in with a metal fire-bucket half-filled with sand to cover it. But there it lay like a crime scene, subverting all our attentions. And thus it was with the exhibition held in the Gallop Gallery at CSU in August 2013, Pictures in a Gallery, curated by Jamie Holcombe. It sought to make the jarring detritus of gallery representation the source material of the exhibition itself. In highlighting the fire extinguishers, the fire doors constantly beeping on audio loop played across the gallery space, at a strident low level, or the snow-drift of white shafts of light as the metal shutters outside the gallery are cleaving like gradually rotating blades across the midday light (all digitally “filmed” and projected continuously within the Gallop Gallery space) as replication of the shadows and shutters slowly wending across the central white gallery wall. It drew attention to the notion of “interruptions” as sole content and occupant of the gallery space in contemporary art.

Figure 7: “Untitled” Digitally “filmed” light, shadows and shutters as shadow-scape. Designed by Chris Orchard 2013 in the “Pictures in a Gallery” exhibition, Gallop Gallery, CSU

The title of the exhibition was conceived by Jamie Holcombe to prompt viewers towards a seeking out of expected Pictures in a Gallery, as a Duchampian interplay with “the gallery” as a series of self-reflexive negations; or rather navigations through its minefields of discordance. It bares “the art gallery” as a construction of “visual noise” that falls between the viewer and the viewed. The bald box of the gallery itself becomes subverted as its own visual and aural repetitions. This is less a series of ironies, than an interplay with expectations of a gallery’s sight lines, and the momentary smoke of illusionism between the real and its imitari. The architectures of art are in a current limbo of lost purpose: the apparatus of the gallery building, the “frame”, drains all consideration away from the intended “art”. The same-scale fire extinguishers on the wall inside the gallery aligns with its exact digital photograph simulation, so that there is the flickering recognition of one being not quite “right”, yet the illusion carries. It is reinforced through a soundscape (designed for this exhibition by Chris Orchard) of an audio loop consisting of the out of hours door alarm beeping constantly, albeit subliminally throughout the gallery. Like an invisible truck backing, the space becomes occupied by this sound with no obvious origin. Unintentionally, it led to staff in facilities putting in a work order to have the faulty door beeping turned off, without realizing it was part of the exhibition premise being broadcast; of the mechanics of the building colliding with its copy. What is left are the conceptual raiments of the image/object in “the gallery” as being privileged and ratified by the white cube.

Figure 8: “Untitled” Digital photographs, hexachrome print on phototex. Power control panel repeated. Exhibition “Pictures in a Gallery”, curated by Jamie Holcombe 2013. Gallop Gallery, CSU, Wagga Wagga

Figure 9: “Untitled” Digital photographs, hexachrome print on phototex, same-scale of power switches and fire extinguisher in the Gallop Gallery, CSU, 2013

Figure 10: “Untitled” Digital photographs, hexachrome print on phototex, same-scale of power switches and fire extinguisher in the Gallop Gallery, CSU, 2013

In further considering Captain Nemo’s porthole, or rather the expansive window through which the world comes to him, our visual culture equivalent might well be that one splayed “window” at the fore of the Starship Enterprise through which Kirk and then Picard accessed the wider worlds. “The window” in popular screen culture manifested itself dramatically in 1966 cult television in Star Trek when it became the all-seeing eye or sweeping “monitor” through which the world, or worlds, flooded in to Kirk’s command chair. Semioticians would consider this a contemporary anticipation of the life lived “in the screen” that the Internet brought to us in regional Australia in 1994. Since then, we scarcely consider spending one day without looking through this window into the worlds that pour through.

This principle of self-seclusion, involving the appropriation of the world and the heaping up of its pieces in a confined space (a literary device which Barthes contends Verne invented, in addition to his use of the innumerable resources of science). (Sebeok and Margolis 113)

The art gallery disports goods and thoughts pulled out of the real world, isolating them for a kind of cerebral attention. Its integral function is not only to provide a secluded, albeit warehouse scaled, “nook” away from the secular world – but to reflect upon it. Its lofty culture requires porous, fluid exchange with mass media culture, not only since appropriation art of the 1980s, or neo-Dada, but since Dada and the dunny in 1917.

The Nautilus contains a pilot’s cage, so constructed as to allow the man at the wheel -often Nemo himself – to see in all directions through four light-ports with lenticular glasses (part 2, chap. 5). This paper aims to focus on only one such conduit, which is a most important and pervasive trope, and perhaps the key figure, used by Conan Doyle: the window. (Sebeok and Margolis 114)

Tracey Emin was shortlisted for the Turner Prize at the prestigious Tate Gallery in London in 1999. Her exhibited work was the verbatim “sculpture” entitled The Bed, consisting of her unmade bed, littered with her personal debris including soiled underpants, empty vodka bottles and used condoms. During the course of the exhibition, two performance artists, Jian Jun Xi, and Yuan Cai, jumped into the bed naked, and jumped around on it for 15 minutes before being dragged away by security guards. In summary, Mr Cai said: “Our action will make the public think about what is good art.” (BBC News 21 May 2000) In effect, the interruption to the artwork outpaces the artwork itself.

A subsequent performance by them involved the most iconic of the Dada readymades – Marcel Duchamp’s urinal which he exhibited in 1917 as Fountain. (figure 11) In May 2000, Jian Jun Xi and Yuan Cai’s performance consisted of going into the exhibition venue in the centre of the Tate Gallery where Duchamp’s Fountain was being exhibited, and urinating on it. “Standing either side of the Fountain urinating for a minute

in front of bemused onlookers.” (BBC News 21 May 2000) I cannot help but think that Marcel Duchamp would have appreciated the irony.

According to Katie Hill, representing the two performance artists: “The aim of the exercise was to make people re-evaluate what constitutes art itself, and how an act can be art.” (BBC News 21 May 2000) An action is only “art” when juxtaposed against the hermetically sealed status of “the gallery”. The gallery rarefies anything contained within it, conferring upon it the transferred status of “artwork”, having conditioned our expectations to receive anything on show within its palace walls as if it is art. We stand in the wings of the artifice, left feeling as if it is something we don’t know enough about, and worse, that our view or response to the work is unnecessary.

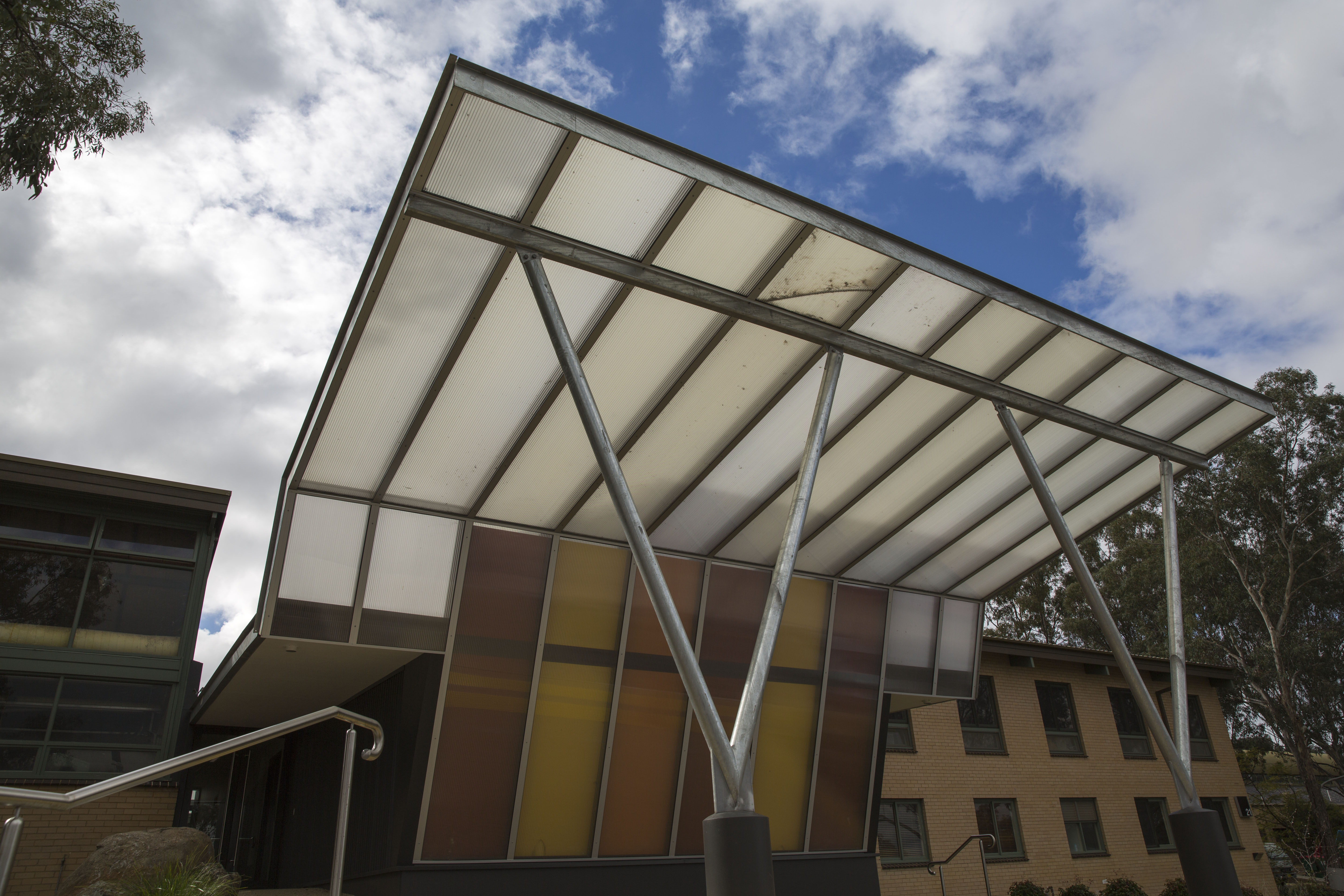

Duchamp repeed; we enter the abandoned industrial warehouse of the “art gallery”and await an arrow to direct us to the art. With Tracey Emin’s Bed, negotiating art from detritus without a scorecard is no easy task. Its used frangers, soiled underpants, and empty alcohol bottles are no Monet water-lilies. It uncomfortably “parks” the fetid bedroom inside the hallowed surrounds of the Tate Gallery. Perhaps that is its value. On the other hand if it smells like shit and looks like shit, it probably is. But it fulfils the Duchampian directive of elbowing the non-art object into the curated realm; it succeeds as gesture. Outside, the drive-in theatre façade arches into an overhead panel, yawning like the truck-stop at Yass. Its windows are not windows per se, only transparent walls. A “window” is intended to pull the outside in; it is not merely a vent towards a blind corridor.

Figure 12: Facade of Gallop Gallery, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, built in 2011. Photograph by Timothy Crutchett.

Figure 13: “Untitled” Digital photographs, hexachrome print on phototex, same-scale as repetitions of fire extinguisher, and fire extinguisher signage. Gallop Gallery, CSU, Wagga Wagga 2013

Figure 14: Facade of Gallop Gallery, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, built in 2011. Photograph by Timothy Crutchett

Figure 15: Digital projection of a trench window from one side of the Gallop Gallery onto the main wall on the other side. Digital work by Chris Orchard. In “Pictures in a Gallery” exhibition 2013

Our innate preference is for the interruption, for the graffiti desecration, the unpredictable gesture. The artwork as dead object lies in state inside the gallery, as the public files by to look at the Turners or Van Goghs, and pay their respects as it entreats our devout silence. The gallery has little accommodation for the irrational gesture. Here’s to Arthur Cravan staging a boxing match with former world heavyweight champion Jack Johnson in 1916 in Barcelona to finally prove which is more important, art or sport. (Art was knocked out in the sixth round with an upper-right/left-cross combination, incidentally, and only lasted that long due to Johnson’s goodwill.)

Figure 16: Poster from boxing match held in 1916 to decide which is more important, art (Arthur Cravan – artist) or sport (Jack Johnson – world heavyweight boxing champion). Dada gesture by Arthur Cravan.

Or as the poet Marinetti outlined a view towards “museum art” in The Futurist Manifesto of 1909:

Museums, cemeteries! Truly identical in their sinister juxtaposition of bodies that do not know each other. Public dormitories where you sleep side by side for ever with beings you hate or do not know. Reciprocal ferocity of the painters and sculptors who murder each other in the same museum with blows of line and colour. To make a visit once a year, as one goes to see the graves of our dead once a year, that we could allow! We can even imagine placing flowers once a year at the feet of the Gioconda! But to take our sadness, our fragile courage and our anxiety to the museum every day, that we cannot admit! Do you want to poison yourselves? Do you want to rot? (Marinetti 1909)

Perceptions of art galleries serving no function apart from putting flowers on the quietly cold graves of dead art were full throttle in the machine age rants of the poet Marinetti, and are no last year’s invention of postmodernism. His rejection of “the gallery” is not based on the contemporary art rift between binary opposites of “static art” versus “moving image art”, but on another of the gallery’s insistences… the unwelcome alignment of opposing or dislocated “images adrift” pried loose from their rightful context and jostled into unnatural alignment with competing works from other time periods, styles, cultures, media and intentions. The “art gallery” as building itself revisits this exact discombobulation of purpose.

Robert Hughes carries this trajectory further in identifying that, even as the installation and performance artists since the 1960s rejected the “art gallery” and its attendant “commodification” of art as object… so too this is not the failing of the gallery, but a limit to the types of art that any “house of art” can display and espouse. He wrote: “A museum can no more contain all culture than a zoo can hold all nature.” (Hughes Ep.8)

When Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, was interviewed by Robert Hughes in the 1970s regarding how ideas were intended to be received within an architecture such as his Zeppelinfeld stadium in Nuremberg in the 1930s, he asked: “And what did Albert Speer expect the ordinary German citizen to feel?”

Nothing. It was not my aim that he feels anything. I had only the aim to impose the grandeur of the building upon the people who are in it. If people who may have different minds are pressed together in such surroundings, they all get unified to one mind. That is really all. (Speer 1978)

Hughes said more regarding this in the light of hindsight from 2003, when he wrote: “Modern art has never had much political power, but modern architecture is a different matter. Architecture is the only art that moulds the world directly.” (Hughes The Guardian 2003) In terms of dominant paradigms of “display” and “collective viewing” imposed by an architecture, although I hesitate to equate the fascist event management of either Albert Speer’s columns, pillars and rows or Leni Riefenstahl’s dark choreography of the camera with contemporary art gallery architecture – the commonality resides in the psychology of architecture imposed upon purpose. “To impose the grandeur of the building upon the people who are in it.” Thus we have state galleries as either hollow pyramids of plastic art grandeur – the monolith… or the shed – these two polar opposites – the purposeless utilitarian shop/office/truck stop just waiting for the defibrillator paddles of corporate decision making to jolt the architecture back into repurposed life. If Hughes is correct and “Architecture is the only art that moulds the world directly”, an art gallery building cannot contain “art” without overshadowing our relationships to it. (Hughes The Guardian 2003)

In describing the museums of modernity, Robert Hughes singled out two as embodiments of prevalent trends in American museology. The first was the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, initiated in 1929, when curation of “modern art” in a traditional museum building seemed an impossibly paradoxical task – and in particular the National Gallery of Art, Washington, East Wing completed in 1978 – about which he wrote regarding new museums emerging since the 1960s that: “most of them looked like fortresses; culture bunkers, radiating an image of vast security.”

The idea of the last bunker in America is carried further by Hughes regarding the National Gallery of Art in Washington, East Wing, in summarising:

If ever a museum set up a building whose main function was to praise its own stature as an institution, this was it… –…the galleries themselves were relegated to the corners. (Hughes Ep.8)

And in those corners, the art itself is squeezed to the further dim edges of our sleeping mindset. A more recent incarnation of this principle might be the Brandhorst Museum in Munich, opened in 2009.

Wealthy financiers in New York such as Solomon R. Guggenheim began building their vast art museums towards the collection of modern or “non-objective” art by 1939. With Frank Lloyd Wright at the helm, monolithic buildings such as the Guggenheim Museum were created either as philanthropy, tax minimisation, or as visible tombs to their creators.

A prime failing of both the “monument” and “shipping container” art gallery options has been in the space actually accorded within the galleries themselves; in particular to recognise the overriding principle that an art gallery needs to be constructed like an iceberg, where nine tenths of it is not in view. This unbelievably has led to the design of art galleries that actually do not factor in provision of any storage space to house collections of works that are not being exhibited, or received artworks crated from other touring exhibition venues, or for ladders, frames, or other equipment storage. Let alone clean, flat space to undertake the required condition reports upon receipt of travelling artworks. It fundamentally misinterprets the role of the art gallery as shopfront only; rather than exercising any prerogative towards archival functions.

The art gallery “monuments” were and are predominantly centralised metropolitan edifices, dependent on the economies of scale of population larger city centres provided. More often than not, the regional art gallery was housed in the outriggers of council buildings, turned uneasily towards an art gallery purpose. Dependent as the regional sector was on bequests and hand-me-down repurposed buildings, old houses and offices became the warehouses of art. In Wagga Wagga, for example – from 1981 until 1999, the library and the art gallery were located in the former Coles Supermarket on Gurwood Street. In 1999, when the new Civic Centre was built with expanded Council offices and meeting rooms, the Historic Council Chambers were repurposed to become the Museum of the Riverina.

Arguably, in a metropolitan centre, such as Sydney, an older architecture carries its own gravitas – the Art Gallery of New South Wales, built in 1896 – was as much to do with draping a sandstone overcoat of culture (or ratified “societal evolution”) upon Australia at the turn of that century – as it was any marker of “art”. Its classicism has effectively evolved through its well planned interiors, creating expanded levels, and through ongoing staff funding.

By comparison, what undermines regional galleries and University galleries in Australia has been the lack of ongoing funding and staffing. The local Council or University funds the building itself as an infrastructure, as if that will be finite upon the building’s completion, without sufficiently allowing for the annual costs of equipping the “gallery space” with an acquisitions budget, lighting, frames, hanging systems, storage, transport, crating, maintenance between exhibitions… and the key issue of the staffing required to ensure curatorial activity can occur within the space. What results can be this empty shell of a factory floor devoid of activity. It singularly fails to identify the role of “art gallery” as more than a static noun, but to do with its continuing actions.

The destruction of intimacy as a precondition to the reception of art derives in part from the cinema aesthetic that dominates the current Centres of Moving Image, where the wall-sized screen in flux is the pre-eminent apparatus. The diaristic, the sketchbook, the hand-held small object very easily lose out in these staggered transactions of the screen. In the same way that the scale of vast digital photographs stretching pinned to gallery walls like so much seductive, filmic, narrative wallpaper removes us from the quieter handling of the 10 x 8 photograph. The removal of “intimacy” as a guiding principle allows the floodwaters of images without meaning to saturate these places, in the interests of instantly digested, visual high-impact turnover cycles. Peter Timms wrote regarding architecture and the current purpose of galleries that:

By their very nature, most galleries do nothing to encourage intimate encounters with the art they show. They are interested in getting as many people as possible through the front door, not in fostering contemplation of the art. Even the most visitor-friendly tend to be cold and unwelcoming, designed to impress rather than reassure. If seating is provided, it will be of the sort that says: “You may perch here for a moment or two, but don’t make yourself comfortable.” (Timms 109)

Windows and shadows cast like ivy, electronic control panels and the shutters they control, banks of lights and switches; all is sleet white, transparency, reflection and mechanism. They seldom provide seating or any wish to have visitors spend time in the space. Like the ghost train, you follow the track from entrance to exit, having been moderately shaken by the jangling skeletons along this narrow line. It is a false encounter, of prescribed cause and effect.

A polite note left in the visitor’s book, and out. The collective herd queues for entrance, and passes through in orderly procession. The traveller enters the white room, and is at once bewildered and disenfranchised.

In appraising the Daniel Libeskind newly designed wing for the Denver Art Museum in 2006, (figures 21, 22, 23) Dr Larry Shiner, the Emeritus Professor of Philosophy and cultural history at the University of Illinois, reflected on the reassigned role of gallery as architecture/artwork, rather than as a neutral house of works:

If Gehry’s Bilbao extravaganza had no galleries that seemed appropriate to their art, if, like Libeskind’s Denver addition, it constantly intruded on one’s experience of the art, would that make a difference – and how much of a difference? Despite the Denver addition’s wonderfully appealing “wild” exterior, whose iconic presence is unquestionably good for the city, the lack of “fit” between form and function is too great not to affect many people’s overall aesthetic response. (Shiner 2007)

The current strategy of architecture towards the gallery often blurs any view beyond. Art galleries now detach from rather than advance art, promoting the art gallery as the artwork itself. For example, the Guggenheim Museum, in Bilbao is a museum of modern and contemporary art more often visited to see Frank Gehry’s architectural design as artwork, not the objects stuck inside it. Since its construction in 1997, it dramatically propelled all subsequent modern art galleries towards concepts of iconic architecture.

Figure 25: Close up of the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain. Photograph courtesy of Jamie Holcombe 2011.

The true home of contemporary artworks may have already moved outside of dependence on any concept of a physical civic building. The evolution of the “virtual gallery”, which exists as online site only, can contain video/computer art without the concessions to veneer or entombment that the art gallery bestows. It arrives at new grammars of relationships, and of the engagement with an individual viewer. Professor McKenzie Wark wrote regarding Jon McCormack’s two-screen CD-ROM installation The Exquisite Mechanism of Shivers that it:

presents a series of perfectly grammatical, but not necessarily meaningful, English sentences, each word of which corresponds to a video image and a sound…all equally grammatical, all strangely senseless, and each creates a new “sentence” of images and sounds. (Wark 52-56)

Even the word “sentence” is being redefined as combinations of image and sound only possible or enlivened in the computer screen, and belying the stolidity of physical art gallery exhibition. These are new media languages of relations that not only do not require the “art gallery” as their humidicrib; they can better exist on equal terms outside of its means of representation.

Up until now, art has remained a resolutely analogue affair. Paint brush moving on canvas, video camera panning across a body, performance art of gestures and sighs. In the appropriation art of the ‘80s, the disjuncture and combination of images emerged as an aesthetic. No longer this image or that image, but the relation, the space, the suggestion in between. Digital media make that in-between the whole of the art. (Wark 56)

These new media languages of the disjuncted alignments of moving image, sound and word were always going to be a televisual concept better suited to the individual viewer of one screen than to the communal or collective viewing apparatus of “the gallery”. It is less a contest of media in the gallery than it is an absence of meaning imposed by this context. If the objects/acts/screens that, like so many vacationing phantoms, inhabit a gallery space for only the limited six weeks or so of an exhibition… make no sense or point beyond their own vague existences, then the gallery itself becomes only another container of endless things.

These incursions of new-artspeak drift from across the borderlands of cinematic language, where Blade Runner’s endless japonic vistas of neon billboards collide with the advent of shopping malls in Italy in the 1880s. These “cathedrals of commerce”, to which Emile Zola referred, mark an evolution of commercialism and of concepts of “shop window” within a purpose-built space that is ingrained in the recent art gallery sector. They are culturally imposed alabaster cages. In as much as the great age of museology entrenched art deeper into the white cubes of galleries since the 1920s, in particular through the various grand American inheritances and bequested art museums – they still all operated there on the one coherent premise of art being collected and preserved, as if spatially pickled in aspic, for future generations. Here, we have the soul-dimmed shopping mall, the commercial shopfront of gallery art, bereft and strip-mined of anything faintly resembling either artistic or architectural pleasure. It is now functional white walls, metal plates, and slit windows with all the aesthetic merit of an armitage lavatory placed in the centre of a shipping container in a dockyard.

In writing an overview of MoMA’s additions of architecture designed by Yoshio Taniguchi – the Museum of Modern Art, in New York – Robert Campbell offered this critique:

Stylistically, the design looks back to modernism, a move appropriate to the museum’s previous architecture and its core collection, but it does so in a building that aims, in Taniguchi’s words, “to disappear,” so that one is conscious primarily of the art. (Campbell 67-69)

This contrasts starkly with both Campbell’s and Ouroussoff’s views regarding Libeskind’s Denver Art Museum addition overshadowing or swamping the art it houses:

Ouroussoff remarks that in a building with “tortured geometries generated purely by formal considerations – it is virtually impossible to enjoy the art.” Littlejohn praises the heroic efforts of the curators, but laments “the apparently brutal indifference of Daniel Libeskind to the work of any artist but himself.” (Campbell 67-69)

And is this art dunny now another perfunctory plumber’s washbasin and metal urinal, and what then disappearing into dust of the museum, which, as Campbell posits above, in reference to the Museum of Modern Art in New York additions in 2004, effectively achieves a “disappearance” of the architecture to give due emphasis to the art collection inside – rather than conceding to the “Bilbao effect” or the overwhelming architectures of a Libeskind – which becomes largely indifferent to anything outside of its own structure. If the art gallery is second-rate shopfront, in an era of uncaged ephemera of hovering projections, sliding screens, and live performance, do we even need its physical presence? Were the Futurists right in wanting to burn down all the art galleries? Could we not store every single thing in the Louvre on a CDRom and save ourselves the walk in their physical space? Why do we value “tactile” touch or sensory experience of dimensions against which to measure the scale of ourselves and our time spent in the presence of? Walter Benjamin’s ideas of “aura” are only a lingeringly vague appeal to the vibe of being in “the presence of”; (Benjamin 219-253) – a presupposed value of direct contact in an increasingly distanced cyberverse where such traffics seldom apply.

Professor Steve Connor, of the University of London, describes this bypassing of the cementing of “the object” positioned inside walls – through sound art devolving these rigid divisions of space, in saying:

So I have outlined a kind of paradox. Sound art is the gallery turned inside out, exposed to its outside, the walls made permeable, objects becoming events. Sound art is the most potent agency of that attempt to dissolve or surpass the object which has been so much in evidence among artists since Dadaism in the 1920s. And yet, the gallery or museum seems to provide a kind of necessary framing or matrix, a habitat or milieu in which art can fulfil its strange contemporary vocation to be not quite there. (Connor 48-57)

Current “art galleries” are announced through their “visual noise” of discordant interruption to thought – they are a dominance of architecture over thought. The architecture exists only as an impediment to contemplation in quietude. The art gallery no longer encourages but defeats this possibility; it offers only artzak… an equivalent to muzak where all is background noise, light, movement, wall, windows and fixtures. We see nothing but the visible trappings of display. The “gallery turned inside out, exposed to its outside.” The “visual noise” bombardment of clutter of mechanisms, from power cords to air conditioners, trench windows, to the metallic shudder of outdoor louvres and grills, fire extinguishers, control panels, silver signage. We make a virtue of the maze, when really it is the carnival of nothingness that is on show; of postmodernism’s posturing advocacy of the meaninglessness of contemporary culture.

Figure 26. Exhibition “Picutres in a Gallery, curated by Jamie Holcombe 2013. Gallop Gallery, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga. Digital photographs, hexachrome print on phototex

Figure 27: “Untitled” Digital photographs, hexachrome print on phototex. Fire extinguishers repeated. Gallop Gallery, CSU, Wagga Wagga 2013.

Figure 28: “Untitled Digital photographs, hexachrome print on phototex. Fire extinguishers repeated, same-scale. Gallop Gallery, CSU, Wagga Wagga 2013

Jack Kerouac’s poem of the sounds of the sea were written at the edge of the Pacific Ocean at Big Sur, huddled in the rain under a sheet of plastic:

and more, again, ke vlook ke bloom & here comes big Mister Trosh – more waves coming, every syllable windy Back wash palaver paralarle – paralleling parle pe Saviour… (Kerouac 206)

All the spaces that the sounds of words create; word pictures, and we close them off from the art gallery’s dictates. If architecture is a kind of music, why do we demand that words are strung like beads? We no longer allow the frame to give the space, the intervals or cadences that the ideas require. Georges Duhamel, the French theorist, wrote a savage indictment of the Americanization of world culture in 1930, in his Scenes de la vie future. His views were seized upon by Walter Benjamin, who used them in support of arguments regarding rapidity of cultural avalanche, and the shift from static image to predominantly moving image culture. Duhamel had written “I can no longer think what I want to think. My thoughts have been replaced by moving images.” (Duhamel 52) Quietude interfered with by the specificity of actions delineated in sequential film culture is all but the precondition of the postmodern art experience. Duhamel went further in devaluing film as a mass culture that was “…a spectacle which requires no concentration and presupposes no intelligence.” (58) I think Benjamin thus calls to the stand a rather unreliable witness in Duhamel; the Surrealists after 1924 embraced film’s potential for the waking dream, so evident in Buster Keaton in Seven Chances (1925) onwards. The doubt left lying is a philosophical questioning of not only why we make images, but what meaning we invest in them, if any. The desire to “think what I want to think” expressed by Duhamel is a protection of the individual response to art, rather than the encroachments of collective response.

Roland Barthes’s central premise surrounded the idea that: “Verne has built a kind of self-sufficient cosmogony.” (Barthes 65-66) Much of Barthes’s conjecture in The Nautilus and the Drunken Boat is towards this dichotomy of infinite travel, in tandem with finite space containing all its own referents. Even while careening the imagination towards the molten centre of the hidden earth, or mysterious islands lost in time… the means to do so is through control of the self-contained world as “pod”. In short:

Verne in no way sought to enlarge the world by romantic ways of escape or mystical plans to reach the infinite: he constantly sought to shrink it, to populate it, to reduce it to a known and enclosed space, where man could subsequently live in comfort: the world can draw everything from itself; it needs, in order to exist, no one else but man. (Barthes 65-66)

The “art gallery” is the last, great, lost avenue mirroring the need for self-referential vehicle. It is a reductive, known and enclosed space, where artworks echo one another across walls. Out of this finite space, a limited set of relationships and meanings are constructed from artworks in, on and around walls… as if they are rare orchids potted down in a steamy greenhouse. It is a temperature controlled realm of the artificial.

The basic activity in Jules Verne, then, is unquestionably that of appropriation. The image of the ship, so important in his mythology, in no way contradicts this. Quite the contrary: the ship may well be a symbol for departure; it is, at a deeper level, the emblem of closure.

…from the bosom of this unbroken inwardness, it is possible to watch, through a large window-pane, the outside vagueness of the waters, and thus define, in a single act, the inside by means of its opposite. (Barthes 66)

The outside world bleeds through the “porthole” window to give context to the art relationships within… this is the necessary symbiosis. The architecture of art bespeaks this delineation of purpose; where the architecture “muddies” this exchange, or arrives at no clear stepping off point into an interior space, and worse still piles both abrupt and diaphanous clutter across eye, ear and the clarity of ideas… we become aware of this visible breach in the hull of art culture’s place within society.

And yet the “art gallery” is an architecture absent of poetry; rather it sees itself as a neutral white canister; if anything it is mathematical, and organizes squares and rectangles towards visual sight lines. That is – which corner we see first when we open a door, or whether we can view a whole wall at once, rather than only in divided increments. An architect would normally be mindful of this as an “art gallery” requirement, but in many cases in this (post)modern era they simply bolt them together today like so many hybrid, assembled panels, kit-form… Any distinctions between kitchen, library, storage, or office are either obviated or scarcely considered. A basic awareness of “sight lines” is less prevalent in understanding the ergonomics of the gallery space than a jar of moon-dust. As a constructed “visual space”, it fails spectacularly in addressing human scale and how people see through the areas created. The distinction between inside space/outside space, and usage is given over to façade; as if it is a plywood set design of a street-scape that has been constructed for a play which will be seen on stage from the rows below, but never actually used or occupied.

Thomas A. Sebeok and Harriet Margolis offer further consideration on the semiotics of windows within art:

In pictorial art, windows often indicate an attention to formal aspects of painting centered around lighting. There is, in fact, a whole genre of window-centered paintings, in modern times perhaps most stupefyingly represented by the Belgian Surrealist master of menace, Rene Magritte (who has, for instance, given us streets of houses at night, their windows illuminated, but with a daytime sky beyond, and, in the multiply equiv- ocal The Domain of Arnheim (1949), a mountain view through a shattered window, of which, scattered on the floor, are fragments of the mountain itself). (Sebeok and Margolis 114)

Magritte accordingly draws attention to the twin realities that exist inside and outside, divided by the thin pane of glass between. Our expectation that the known world continues undisturbed beyond that glass window is unfounded.

Art galleries enact distinctions between inside and outside space, between public and private space, and between the intimate and the expansive. The failing of an architecture is where it cannot differentiate these differences, and confuses the spaces it creates and renders them as functionless as Man Ray’s flat iron spiked with nails.

We are purveyors of the package, and of the submarine… the vessel is more important than the destination. In terms of habitat, where we live and how we occupy space, we are cannibals of the already known. Rituals at once familiar are enacted, of being seated in a theatre-space, and applauding at the conclusion. All these rituals of performance; or delivery and receipt become untangled in the digital world where we seek to impose equivalence… to shoe the horse, whatever horse or zebra it might be. The arrogance of gallery artists lies in their presumption that it is a good idea to add more artworks to the world. Clinging as we are to the lifeboat of modern art, why is this the case? There is no protected or given reason why exhibited paintings, drawings or other gallery objects need this hothouse six-week bloom and droop in the space of a gallery.

Against this backdrop, the University sector continues to enshrine written research as the model imposed upon practice-as-research modes. Art practice is tolerated as if it is a magician’s party trick, conducted prior to the serious business of “translating” practice into written thesis – notionally, that art research always requires “validation” by text. In part, because we distrust the flawed imprimatur of the gallery “publication” by exhibition. The art gallery’s failing as a frame for contemporary art, as other than some gaudy fairground ride, casts art-makers further into the deep shade of the written “thesis” as legitimate research outcome.

The elevation of critically writing about things being considered more important than making them has since the 1970s given disproportionate power to theory over practice, and of writing over gallery exhibition. If anyone doubts these continuing incursions of obfuscationist language in 2014, a brief glance through current issues of ArtAND and other current art periodicals can readily confirm it; from the dense art writing in the Moscow Biennale catalogue of October 2013 to the ponderous gumph of the Sydney Biennale catalogues. “Practice as research” spends far too much of its research intent in the numb business of “recoding” exhibition outcomes into the word; the University research-object outcome as written exegesis, leaving practice based researchers constantly walking blindfold through pointless paddocks, collecting up pats of data along the way. It is often data collection without point or purpose, as an encouraged academic “evidence” of enquiry. In essence, the art historians manufactured these preconditions, and are only ever engaged in the act of returning books from trolleys to their rightful places on the shelves. Their core business is only to catalogue and locate all manner of things in their proper slots.

If the value of art still resides in the conditions of its making, we might well heed the still insistent voice of Walter Benjamin that “the earliest art works originated in the service of a ritual – first the magical, then the religious kind.” (Benjamin 219-253) If the magician/artist enacts transforming rituals from the outside, becoming visible to others only through – the shed/the basement/the memory library-van/the sketchbook reservoir/the pictoglyph hoarder – If an art collection is always a warehousing of the past, and the routine compiling of the discarded pieces of our forgotten inner lives, it is then ripe for pinning and formaldehyde, image-scavenging and the scrutiny of myriad violent juxtapositions. Art gallery as location of ritual and pilgrimage fulfils our desire to be in the presence of an original work… it is a lost appeal to the validity of first-hand experience that swims against the riptide of every other cultural form prevalent in current society, where a life lived in the screen becomes the only daily validation, and transmitted mobile phone images and words are the only legitimised, constant oxygen.

The art gallery as space and as habitat is the bond slave of architecture – it has increasingly less to do with traffic and trade of ideas, let alone magic. Disembodied visual poetics creates not one lone answer, but argues for art research as choices between possible outcomes – the new language relies like the pittura metafisica of De Chirico on willingness to want to see “the meaning behind… the ordinary.” – That beyond the smokescreen artifice of interactivity, and the terrains of virtual realities – lies our essential humanness, (and whether by plane wing/black box/snow cube or Glass Eye) we return to seeking to make visible that which is hidden or cannot be apprehended by the eye – to reinstate mystery, to achieve different voices/to express. In recognising the hollow appeals to “interactivity” that digital arts often rests upon, the former lecturer in multimedia arts, Dr Johannes Klabbers, said:

The work has evolved away from interactivity – no clicking – it is now linear or random. Interactivity is no longer interesting to me… if you leave the thing alone it does its thing… if you leave truth alone it turns to beauty. (Klabbers 2003)

One of the key masquerades as “art” rolled into the 21st century was in this sanctimonious assertion from digital artists that their works offered “interactivity”; as if newness alone constituted value or originality. All art has always been “interactive” in its requirement upon the viewer/beholder to complete it; and in the time spent in the presence of that work. We seldom hear “new media” artists discuss their aesthetics in terms of intention towards beauty and the sublime, in favour of rabbiting on about the programs used to produce it, so that Klabbers’s aesthetics of poetic disjunction remain disarmingly humanist. Professor McKenzie Wark, Australian born author in new media, (and currently Professor of Media and Cultural Studies at The New School in New York City) wrote extensively about the spiralling advent of new media aesthetics here in Australia in the 1990s, and identified this same discussion of “interactivity” quite neatly in saying that:

It’s not that multimedia is somehow more “free” than any other media, or somehow “more” interactive. Interactivity is a quality, not a quantity. Multimedia offers different kinds of interaction, not more of it. Indeed it may even offer less. (Wark 52-56)

We need to stop deferring to “interactivity” as if it implicitly has meaning just because we activate it through different physical or psychological cogs and levers, any more than any other amusement arcade. From site-specific sculpture or installation art, to performance art or land art…the photo-documents of performance/site-specific artists such as Jill Orr or Andy Goldsworthy underscore the fact that “the gallery” remains too small a stage for these performative concepts, albeit in the screen or human scale against the landscape. The book or digital archive pulls us into Goldsworthy’s sculptural landscapes more expansively than the atrophied gallery photo-record; his venue is the virtual gallery. It is not the computer’s capacity for interactivity or even navigation that allows this; it is its fluidity to align the “virtual exhibition” towards intention in size, scale, relationship and access.

Figure 30: Andy Goldsworthy “Woven branch arch, Langholm, Dumfriesshire” 1986 site specific land art, digital archive. copyright Andy Goldsworth/ and the University of Glasgow.

A window, a ladder to the stars, a doorway, a moon, a chair, a dark great coat, a white sentinel dog, a burning rope, a pair of rumpled boots… that is Van Gogh, Paul Klee, Chagall, Peter Booth and Tim Storrier in one time-dissolving brown-wrapped package. The art museum or art gallery is now only a Bates Motel warehouse of the living dead, anchored in the past. Klik-klak on high-heeled shoes, leopard-skin leggings, black suits and shirts… its custodians and keepers patrol their polished concrete, hard wood or industrial black rubber floors with various white commandments of foam-core titles-and-text to stick neatly near the bottom right-hand corners of “the art”. The art is clarified by its physical proximity to the text, and by the gallery/museum’s cultivation of tourist traffic of fast-food translations of the creative arts into written language.

Professor Connor rails against the “ocularcentricity” of the gallery, and that the gallery itself as constructed notion defines art as visually directed. Duh. But we have since 1994 created internet “virtual galleries” that do obviate the need for the physical “cage” of the walk-through gallery space; in fact, the computer better houses moving image and sound works through computer art online. Again with computer art, we have been acclimatised to view it at the scale of the grey-box computer. In the same manner that “reading” a Daguerreotype in the 1840s or a cut-off snapshot photograph by 1890 was learned through gradually acquiring the “grammar” of seeing many of them, so too is computer art a nurtured language we have deciphered and become acclimatized to. We do not “require” wall-sized work to visit or receive computer art. In writing about habitat in 1973, Barthes ruminated on this “gate-keeping” activity in demarcation of the territories we use; he anticipates this cyclic flow of the visual and sound towards the one omniscient screen.

Art today is always mediated through the technology that has produced it. We remain in thrall to the magic curtains of digital photography, and longer still to the arcane chemical ponds of the analogue photography darkroom, or of printmaking’s etching plates, acids, and aquatints. These are the hidden alchemies of arts that chemically reveal themselves through fogs of unknown wizardry. Most of all we defer to the machine mysteries of new media’s computer generated image-worlds, either in graphic design or moving-image animation. We seek to hold onto the “art gallery” as refuge in the forest… to retain it as an unmediated space that does not impose its structures and advance readings upon the viewer/user/traveller to the interior site of exhibition.

We speak today of living “in the screen”, of engaging images through receipt. We never have to become pilgrims to reach a site where art generates its aura or exists in its own preconditions, it is all received and it all comes to us. At a conference entitled Drawing Connections in July 2003, the then Dean of COFA, (College of Fine Arts), University of New South Wales, Ian Howard said regarding drawing and its applications within digital arts practice that:

Through the mediation of technology there is always the creating of a generalized experience. Through information technology there is always an expectation that things will come to you, not come from you as an independent vision. (Howard 2003)

I think Howard’s comment identifies the precondition of the disfunctionality of the art gallery towards contemporary art. We see it only as generic wrapper – another building we traipse through rapidly, our walk-through-art punctuated by one mobile phone call stepping to the next, and ending at the gallery shop to look at the postcards. We are less likely to stand contemplatively in this “art gallery” environs than 30 years ago. We are conditioned to register an exhibition’s “ideas” rapidly on the retina, and then move along. The visual noise of its architecture is as dialled down to us as any other ambient noise of cafes with blaring radios, advertising, internet, text, ning, twitter, text, skype and blog. We are less receptive to pilgrimage, to shared common event, to aura dissipated into the shadow-realm grey-lands of data.

The relationship between handwork and the computer generated, these composites of information, style, idea traffic, availability, ease and difficulty, are paramount concepts that need to be deliberated upon… individually and within the collective dynamic, if we eventually conclude that each offers a different parallel experience and vision of the world and visual culture. Increasingly, we approach the “art gallery” as if it is one floating vessel of that information; one that we might simply use as a rapid departure lounge towards other more significant destinations.

The concept Howard raises of “generalized experience” is ill-served by generic IKEA prefabricated designs for art galleries, all equally bland and unfolded from the same flat-pack, and equally unsuited to the task. Peter Timms, a previous director of the regional Shepparton Art Gallery, and an art critic for The Age during the 1990s, offered this provocation:

Many contemporary art museums, such as the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne, seem designed as statements of naked power and intimidation. Not even the most seductive art can induce us to linger in such hostile environments. (Timms 109)

The inbuilt intimidation and parade of palace ghosts these “art museums” construct is a clear curatorial aesthetic of the turnstile, rather than of a library where one is enticed to stay. The foreboding architecture, all portcullis and moat to the unwary and unanointed, is part of this “executive key to the washroom” mentality that trades on making the visitor feel reduced in scale. Albert Speer would have approved. It is an odd point of history when the art gallery and fascism chant from the same song-book. Art fascism is about cloaks of self-importance being enfolded over public spaces, and valuing “unified” space above individual autonomy within it.

The Finnish architect, Juhani Pallasmaa, former professor of architecture at the Helsinki University of Technology, addressed this paradox of purpose/lessness in a lecture he gave in 1999 regarding disappearances of “beauty”. He wrote:

The pleasurable experience of vernacular settings arises from a relaxed sense of appropriateness, causality and contextuality rather than any deliberate aspiration for preconceived beauty. In our culture of material abundance, lost in a spiritual desert, architecture has become an endangered art form. It is threatened by quasi-rational, techno-economic instrumentalization, on the one hand, and the processes of commodification and aestheticization on the other. Paradoxically, architecture is simultaneously turned into objects of vulgar utility and objects of shrewd seduction. (Pallasmaa 207-1239)

Now I’m not entirely sure what “quasi-rational, techno-economic instrumentalization” is, but I suspect I’m standing in it. On the other hand, architecture as “vulgar utility” is a descriptor readily apprehended by all of us. It betokens a secular disintegration of the spiritual in art and architectural design philosophies. Architects designed better churches when they thought God was going to hold them to account if they didn’t.

If we are immersed in the submarine world of the cloud and the web, where all information comes to us on the portal of the screen… why does the physical shell of the white cube gallery retain any potency or language? What is there that we expect to be in the presence of? The cathedral of commerce, the high-church of art… all is mystification and doorway world to Narnia’s snow-filled promise.

If we consider the effect of these three technological applications (surveillance, cellspace, electronic displays) on our concept of space and, consequently, on our lives as far as they are lived in various spaces, I believe that they very much belong together. They make physical space into a dataspace: extracting data from it (surveillance) or augmenting it with data (cellspace, computer displays). (Manovich 5; 219)

In considering the poetics of augmented space, Lev Manovich comments on the increasing spillage of surveillance across our concepts of lived space. We walk in the perpetual red shadow of monitors, flashing lights, electronic eyes, windows, scrap wording, neon slivers, and fire extinguishers. All are the casings of data set in place to compete for our fickle and transient attention. Beauty is a concept with no place left in this spreadsheet. We stand unsteadily upon the sugar cube dissolving in modern tea.

Bibliography

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space, Beacon Press, 1958, ed. 1994, p.29.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies, Vintage Pub., 1973, pp.65-66.

BBC News, 21 May 2000.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, 1936, in Illuminations, London, Jonathan Cape, 1970, pp.219-53.

Campbell, Robert. “What’s Wrong with MoMA: Disappearing Architecture and a Sense of the Unreal,” Architectural Record, 193, 1 (2005), pp.67-69; ref. on 67.

Connor, Steve. Bodily Knowledges: Challenging Ocularcentricity, pub. FO(A)RM, 4 (2005), 48-57.

Duhamel, Georges. Scenes de la vie future, Paris, 1930, p.52.

Howard, Ian, then Dean of COFA, (College of Fine Arts), University of New South Wales, at the conference entitled Drawing Connections in July 2003.

Hughes, Robert. Shock of the New, BBC Pub., 1981, Ep 8.

Hughes, Robert. The Guardian newspaper, 1 February 2003.

Kerouac, Jack. Big Sur, Andre Deutsch Ltd., 1963, p.206.

Klabbers, Johannes. A Limited Catalogue of EndlessThings, cat., Wagga Wagga Art Gallery pub., 2003.

Manovich, Lev. The Poetics of Augmented Space, Visual Communication 2006; 5; 219 Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi: http://vcj.sagepub.com

Marinetti, F. T. The Futurist Manifesto, 1909, published in the Italian newspaper Gazzetta dell’Emilia in Bologna on 5 February 1909, translation from James Joll, Three Intellectuals in Politics.

Morgan, J. and Welton, P. See What I Mean?: An Introduction to Visual Communication. London, Edward Arnold pub., 1992, pp.15-33.

Overton, Neill. A Limited Catalogue of Endless Things, 2003, Wagga Wagga Art Gallery pub., Feb, 2003.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. Hapticity and time: Notes on fragile architecture, Architectural Review 2000, Vol 207 Issue 1239.

Rees, Lloyd. Late Drawings and Lithographs, cat., Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston, 1982, p.11.

Sebeok, Thomas A., and Harriet Margolis. “Captain Nemo’s Porthole: Semiotics of Windows in Sherlock Holmes.” Poetics Today 3.1 (1982): pp.110-139.

Shiner, Larry. Contemporary Aesthetics, (CA) Pub., University of Illinois, 2007.

Speer, Albert, in interview with Robert Hughes in 1978, The Guardian newspaper, 1 February 2003.

Timms, Peter. What’s Wrong With Contemporary Art?, University of New South Wales Press, 2004, p.109

Verne, Jules. 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Pierre-Jules Hetzel pub., 1871, illustration copyright Alphonse de Neuville.

Wark, McKenzie. The Terminal Garden. World Art, 1, 1995, pp. 52, 54-56. (54)

About the author

Dr Neill Overton is a Senior Lecturer in Art History and Visual Culture at Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga. His research interests are in contemporary Australian drawing, art prizes, awards and surveys. He as a lecturer at RMIT, Victoria College, and Melbourne University in Art History and Drawing, and worked extensively as a newspaper illustrator, exhibiting artist, art reviewer and novelist. He has curated major exhibitions towards histories of Australian film , theatre and television. His PhD was on Icons and Images in Australian Drawing 1970- 2003, and his critical essays address the relationship between contemporary regional and urban art.