Kampung (village) Dreaming: rural and urban icons of Malaysian modernity in the cartoons of Lat

Authors:

Nasya Bahfen, Monash University, Australia

Zainurul Aniza Abd Rahman, University Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

Juliette Peers, RMIT University, Melbourne

To cite this article

Bahfen, Nasya, Zainural Aniza Abd Rahman and Juliette Peers. “Kampung (Village) Dreaming: Rural and Urban Icons of Malaysian Modernity in the Cartoons of Lat.” Fusion Journal, no. 4, 2014.

Introduction

The kampung or village holds a complex position in Malaysian government narratives of national identity. It is a place of respite and retreat from the implied government agenda of a modern, Muslim-majority, democratic nation-state (and the accompanying paraphernalia that envisioning of Malaysia implies – the urban centres, the international trade, the tourism). At the same time, the kampung is cherished in official narratives, raising a dichotomy reflecting the point of impact of rural and urban tension. On the one hand the kampung seems quaint and rustic when Malaysia seeks to imagine and project itself as a global, urban, progressive powerhouse – all tall buildings and the first Muslim astronaut while also conscious of an Islamic renewal. On the other, it is sold to both Malaysians and foreigners as a site of an authentic, genuine, traditional and rural Malaysia that differentiates the country from generic South East Asian globalised cultural expression.

This article looks at how Malaysian national identity was constructed through the stereotypical icon of the kampung and its urban counterparts, in Lat’s cartoons. Lat made significant contributions in portraying images of Malaysia’s nationhood through his cartoons, which depicted both nostalgic rural imagery and changing urban life to promote Malaysia in the international arena. The late renowned Malaysian art critic Redza Piyadasa described Lat as having “elevated cartooning to the level of ‘high visual arts’ through his social commentary and “construction of the landscape” (Lent, 2003). Lat’s cartooning work has received international recognition, and he has been rewarded with the highest honorific title possible for a civilian in Malaysia (the title Datuk was conferred upon him in 1994). Accordingly, we privilege Lat in this paper, over other popular Malaysian cartoonists.

In an attempt to outline how Lat and his cartoons played various roles in depicting visions of the kampung, our paper begins with a brief exploration of the role of the media in documenting Malaysian national identity, and an introduction to Lat. We then explore the urban and rural themes found in a selection of Lat’s work, suggesting that through entertainment and humour his work has had a unifying effect on Malaysians by recording the urban centre as a part of Malaysian nation-building, the nostalgia of the village and changing norms in society, and reflections on shared urban and rural humour.

Malaysia, truly (mediated) Asia

Icons, symbols, images and graphic forms, are able to convey specific multi-layered messages to viewers, which Bamford and Francois (2001) refer to as ‘a diversity of meanings’. Cartoonists use visual signs to communicate in their work. In the process of national identity construction, cartoonists condense meaning through metaphor, allusion, and metonymy, and they significantly contribute in constructing new worlds of understanding. These iconic images produced new understandings or emphasise a myth reproduced through ephemeral print media such as newspapers, magazines, cartoons, posters and brochures, promoting important symbolic representations of national identity (Edwards, 1997).

The development of Malaysian national identity required the use of media such as radio and television in the early years of independence as the number of literate citizens were limited. Later, as the literacy rate among Malaysians rose (Pandian, 1997; Karim and Hassan, 2007), visual and print media became the main tools for the Malaysian government to promulgate national ideologies. Most promotional activities were heavily involved with the creative media industries, such as television, film, theatre, advertising, graphic design, and popular print publications (such as women’s, children’s, religious, film, and tabloid magazines). But the space provided for creative industries practitioners such as cartoonists, graphic designers, actors, film producers, writers and journalists, was limited and determined by government regulations.

The concepts of social liberation or freedom of expression in the Malaysian popular print media were promoted within the paradigms dictated by the Malaysian government (Milne and Mauzy, 1999). The space and liberty provided for the creative production industries was restricted under government ownership or legislation, and most significantly the process was robustly guided by press ideology, making it difficult to determine where government interference stopped and media self-restraint commenced. Lent (1974) maintained that Malaysian mass media are constantly controlled by the government rules and legislation for the purpose of sustaining and promoting national unity.

Similar to other creative industries practices, cartoonists in Malaysia were tied to the given agenda provided by their client or sponsor. Their work and productions were very much restricted towards the content requirements of the agencies, and also narrowed down into illustrating areas that concealed sensitive issues in relation to religion, sexuality, ethnicities rights and political influences. Not only were they are not able to control their own sketches but they were also prevented from keeping their cartoons’ copyright. Their cartooning activities were very much controlled indirectly in Malaysian print media, by the Printing Presses Act legislation and by ownership (Lent, 1999; Muliyadi, 2004).

Lat’s Story

Born in Kota Bahru, Perak, 1951, Mohamad Nor Khalid derived his cartoonist name ‘Lat’ from his childhood nickname bulat (literally “round”), which was the nickname given to him due to his chubby looks as a child. Kota Bahru is a small rural town close to the city of Gopeng, in Perak state, in the northwest of Peninsular Malaysia. Early memories growing up in a village setting had a significant influence on the way Lat constructed his cartoons and the way his characters developed through the years. Throughout the years, Lat has published more than thirty books which contained compilations of his cartoons published in newspapers such as Lots of Lat, Lat and Gangs, The Portable Lat and Dr. Who? Apart from these compilations, Lat published four bestselling graphic novels – retrospectives of Malaysian life which were also regarded as Lat’s de facto autobiographies: Budak Kampung – Village Boy (1979), Town Boy (1980), Mat Som (1987), and Kampung Boy: Yesterday and Today (1993). Unusually for Malaysian literature, these books have had a significant global presence. They have been translated into various languages, such as French, Japanese, German, English and Arabic (2010), and have been published internationally. Lat also extended his cartooning activities into animation, by transforming the Kampung Boy series into a television series for pre-school and primary school children on the private television network ASTRO in 1988. One of the 26 episodes won the best animation award at the Annecy Animation Festival in France in 1999. The show was aired in Germany, Canada and on SBS in Australia. In 1993, Lat was invited by the Asian Cultural Centre for UNESCO to produce an animated, sixteen-minute literacy campaign. The animation series called Mina Smile was produced to support the underprivileged in Asia. Lat’s career and oeuvre and the iconography of his cartoons have been the subject of academic studies as well (Rahman 2012).

Lat as chronicler of rural nostalgia

The concepts of city and country (such as scenes of kampung life, and skyscrapers, restaurants and other depictions of urban life) so eloquently and perceptively imaged by Lat inform core constructs of the political and cultural identity of Malaysia – and how these city/country region contrasts and interplays are points where government endorsed national identities become manifest and gain a dynamic energy. Lat clearly indicates this through his work. In one of his most well-known cartoons, a Malaysian of the majority Malay ethnic group is depicted on a conveyor belt being changed instantly from a troglodyte villager to a corporate entrepreneur. It is Lat’s subtle and sceptical reaction to the notion of a Melayu Baru or ‘New Malay’ – the catchall phrase reflecting the desire of the Malaysian government of the early 1990s to capitalise on the growing Malay middle class whose characteristics were international educations and cosmopolitan tastes and incomes (Chong, 2005).

Lat demonstrates the construction of Malaysian national identity whether his characters are sited in rural or urban settings. The Scenes of Malaysian Life series appeared three times a week in the New Straits Times newspaper from 1974 and ran every week until the end of the 1970’s. Public access to this early NST editorial cartoon series is very limited, and the date of each cartoon’s publication is either not stated, or the cartoons have been grouped under various dates. The series appeared to act more as a cultural documentary, presenting various ethnic cultures and tradition, in ordinary day-to-day practices and customs (weddings, festivals, eating habits, or people on the street). Like kampung Boy, in the series Scenes of Malaysian Life Lat presented an idealised view of village life, in a mélange of topics about different races’ traditions and customs, national histories, tales and places, and nostalgic memories through old movies, songs and drama.

Ethnicity is one of the core parts of the visual representation of Malaysian identity. The Scenes of Malaysian Life series expressed the outward trappings of an idealised rural existence for major ethnic groups in Malaysia. On an official level Malaysia is made up of four main ethnic groups – Malay, Chinese, Indian and Indigenous (Hirschman, 1987). However, the representation of ethnicity in Lat’s Scenes of Malaysian Life provides another

perspective, recalling villages of many different ethnicities (ethnic sub-groups in rural society). In the earliest series of Scenes of Malaysian Life the subjects of the stories are not focused under the “main” ethnicities of Malay, Chinese, Indian and Indigenous Malaysians drawn upon in state ideology and documentation. Instead they are depicted as sub-groups of each community – specifically, Malays from Perak, Sikh Indians, and Hakka Chinese. While these sub-groups have not vanished from Malaysian society and still practice their discrete customs and dialects, unlike Lat’s depictions of them in his early cartoons, on an official level today images of their cultural practices and norms are non-existent, or subsumed into the meta-narrative of modern and multi-racial Malaysia.

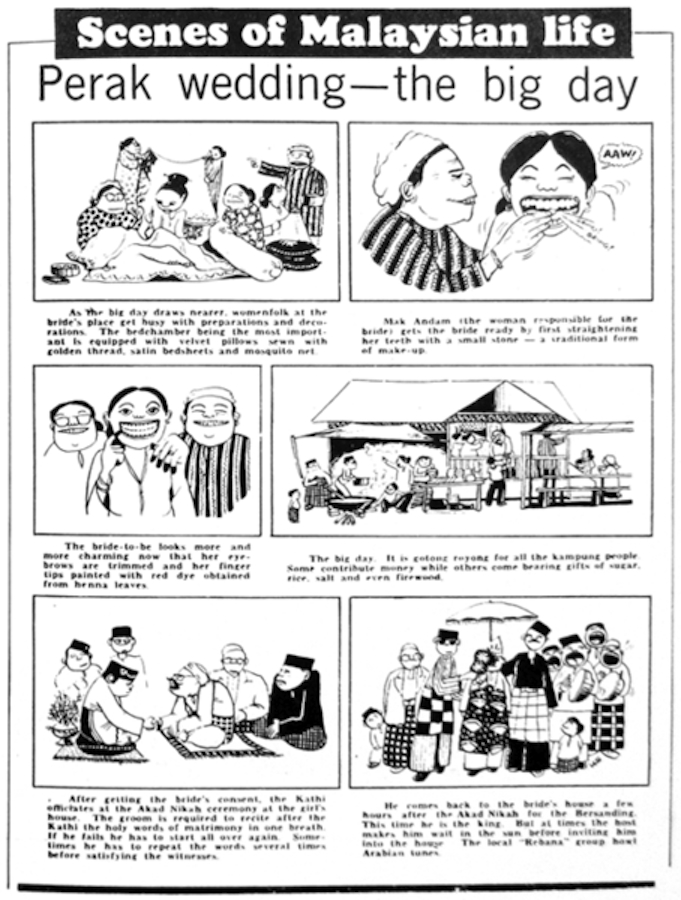

The first edition of Scenes of Malaysian Life was entitled A Perak Wedding (The Big Day), which consisted of a series of visual narratives about Malay wedding ceremonies done in Perak (see Figure 1). The cartoon strip was published continuously every week from 4th to 7th March 1974 in different segments. In these series, Lat visually records the Malay wedding ceremony from Perak (one of the states situated in Peninsular Malaysia). The stories narrated the extensive wedding activities from beginning to end: the preparation of the wedding day, the decorating of the bride’s house, the roles of the Mak Andam (make up artist or beautician) in grooming the bride, gotong-royong (communal activities), where the entire village gets together to help the bride’s family to cook and prepare, the akad nikah (wedding registration ceremony) and adat bersanding (the tradition whereby the bride and bridegroom sit on a platform or stage to present the newlyweds to relatives and friends). For the first series, the selection of the cartoon strips was published as a trigger to attract the readers’ attention for the complete cartoon series.

The other series chosen to be part of Scenes of Malaysian Life cover ethnic sub-groups of Sikh (representing Indian ethnic) and Hakka (representing Chinese ethnic) communities, and their traditional weddings. Sikhs are the second largest Indian ethnic group in Malaysia after the Tamils (Sandhu and Mani, 1993) while the Hakka make up the second largest Chinese ethnic group in Malaysia after the Cantonese (Carstens, 2005). Lat stated his interest in portraying the Sikh man with a turban in his cartoon drawing, and the difficulties he had face in order to gather stories about the Sikh wedding for his cartoon strips. Given his unfamiliarity with Sikh marriage customs, Lat had to experience the wedding. In response to the question asked by his fans about the regular appearance of a man with a turban in his cartoon, Lat wrote:

I tried to bring out things that were very common but which we didn’t know the details of. I had wanted to know how the Sikhs got married.

Both portrayals were published in the local mainstream Malaysian English newspaper, The New Straits Times in 1974 when Sikhs appeared to be representative of the Indian ethnic group – a role played by the Hakka for Malaysian Chinese, at the time. The series set the stage for Lat’s establishment as a chronicler of multi-ethnic rural Malaysia, known by many, in informing and stimulating curiosity about traditional roots, national history and cultural practices.

Scenes of Malaysian Life were part of the New Straits Times’ trial project to encourage the notion of nationalism and, to support nation-building developments by drawing on the kampung experience (Rahman, 2012). Specific topics involved with Malaysian local custom, tradition and national visions were regularly reintroduced, and restated along with the facts of national history. The series of editorial cartoons in the New Straits Times continued on a weekly basis for nearly twenty years, even though the original title Scenes of Malaysian Life was no longer used after several years.

Lat as narrator of urban progress

Most of the icons used in Lat cartoons, were based upon his early school education in the kampung or village, but which represented the narrative of Malaysia as taught to country and city children (Rahman, 2012). The events Lat alluded to in his cartoon strips are mostly popular historical facts that are known by most Malaysians who had been through public schools using narratives which largely permeated history classes. In order to promote the notion of national identity, cartoonists (similar to many visual communicators such as graphic designers, architects, film makers, and visual artists) borrowed some of the popular stereotypical icons whose meanings are widely known and understood by the society. These icons were reproduced mainly from official historical statements or documents derived from several branches of the stereotypical icons that are shared and understood by Malaysian society. For example, the flag representing all Malaysians, or the national flower, or iconic buildings representing Malaysia’s urban progress in its modernity project. Together these icons could be said without exaggeration to represent the essence of Malaysian community.

National history in Malaysia, like many countries in Southeast Asia, is mainly based on the knowledge of national history as a ‘given’ ideology rather then understanding processes through critical discussion. Notions of nationalism, acquired progressively through the country’s promotion of nation building activities and national history, include pride, sacrifices, achievements and celebrations (Billig, 2010). Most of the icons seen in Lat’s work are based on the stereotypical notions of history. One of most significant examples is Merdeka Day (Independence Day) – a national day that is celebrated every year on the 31st of August. Approximately a month before Merdeka Day, Malaysian citizens will be reminded through advertisements on television, radio, and print in newspaper and other printed materials, about their national origins including their country’s achievements to be proud of.

History therefore plays a prominent part in the media’s promoting of the country’s national identity and historical imagery has been strongly used in depicting the notion of a Malaysia steeped in the iconography of modernity and progress, as represented by the accoutrements of the urban centre. A key example as highlighted in Malaysian tourism websites and brochures is the Kesultanan Melaka or the Malacca Sultanate era (1401 to 1511) which is perhaps the most important period in the timeline of pre-independence Malaysia. Milner’s work on historical elements as parts of nation building narratives in the Malaysian context argued that one of the agendas promoted by the British in their involvement with Malaya as British Malaya is the emphasising of the bustling port city of Melaka as embedded in Malaya’s and later Malaysia’s nation-building narratives. Based on the analysis by Shamsul Baharin’s entitled Malaya dan Tawanikh Dunia (Malaya and the World) (1962), Milner (2005:133) argued that

Melaka is not discounted as part of the national narrative. It is used to help explain the Malay background, as other pre-modern narratives are employed to help the understanding of the other peoples of the peninsular.

Lat’s cartoons draw heavily on historical narrative, and are sketched through an understanding of his quintessential kampung roots making him a “rare phenomenon – a genuine ‘Malaysian’ in his artistic outlook” (Piyadasa in Lat, 1994:39). Azmi (2009) praises Lat as one of the main reasons for Malaysians sharing an identity regardless of their country or city origins and irrespective of the ethnicity they belong to. Away from the political and racial issues that have marked Malaysia’s recent history, Lat’s cartoons seem to be the ground for Malaysians to reflect on national achievements and the struggles the nation went through. Accordingly, in one of Lat’s early cartoon strips in the Scenes of Malaysian Life series called Down Malacca Way the Malacca sultanate plays a key role. He takes readers to revisit the Melaka (Malacca) of the past, with the setting on the bridge that connected the fort and the mainland. In this series, Lat draws eight panels of cartoons from the same position of Melaka Bridge but with different scenes. His first four panels drawing different scenes of Malacca begin with:

Oh! Malacca… everywhere I look history grips me. I was contemplating her river from the old bridge near the river mouth… and full aware that I was on the focal point of the Portuguese attack…

The second set of four panels continues with,

Nope, I just couldn’t stop it. Down in Malacca town my train of thought carried me far far away. There was even Hang Tuah and his close friends. And just as I sat by the sea in Taman Merdeka, a wifely gift to Sultan arrived from Peking. It was amazing. There were hundreds of international traders… Arabs, Gujeratis, Parsees, Sumatrans and Chinese… with everything from tobacco to jewels. It didn’t take long for me to get back to the present. The traders were apparently local ones selling cheap souvenirs and cencaluk.

Bustling Melaka is not the only historical urban location of importance to Malaysian history and strongly embedded in the Malaysian nation building consciousness, which is depicted in Lat’s editorial cartoons Scenes of Malaysian Life. Another series invoking the metropolitan facet of Malaysian national history is about the capital city, Kuala Lumpur, told in Lat’s work through a Chinese Kapitan (captain) known as Yap Ah Loy, and a Malay Sultanate, Raja Abdullah. The series’ first appearance in the national newspaper, the New Straits Times entitled Yap Ah Loy Revisits Kuala Lumpur. The series was published in the newspaper between 25 to 28 March 1974. In the latest New Straits Times publication about Lat early series of his work published in 2009, the series of Yap Ah Loy has been modified where the name Yap Ah Loy has been dropped and the title has been changed to Kapitan China (Chinese Captain) Revisits Kuala Lumpur.

Lat as a reflection of urban (and urbane) Muslim Malaysia

Malaysia gradually moved from a western-based society to a progressive modern Islamic society (Chong, 2006). Sanusi, Mansor, and Abdul Kuddus (2008: 215) outline the development of the Malaysian bureaucracy from independence to 2003 placing that development within the wider context of the influence of an Islamic resurgence in Malaysian life.

Islamic revivalism spread among the Malay/Muslim community. Traditional performance in public involving both sexes like dancing declined. The official Malay joget (a dance originating in Melaka) and ronggeng (a form of Javanese dancing and singing), so popular at office and official functions during the administrations of Tunku Abdul Rahman [1957-1969] and Tun Razak [1974-1976], went out of favour.

As much as the country evolved economically, it became more conservative – a trend reflected in Lat’s cartooning activities, and his depictions of Malaysian national identity. The imagery of the kampung serves to inform Lat’s inadvertent recording of this change in social and religious mores, and assists the audience in its reading of this trend. For example Lat depicts Joget Lambak (traditional Malay dance in public) as a traditional event commonly organised by kampung or village residents, on the night after a wedding ceremony to celebrate the newlyweds (Bujang, 2005). Over time it became a popular activity included in Malaysian tourism, during two generations of Malaysian Prime Ministers from the 1960’s to the late 1970’s. The popularity of Joget Lambak as a social event involving the whole village has been reduced over the years although it is still performed at tourism or official events (Ammirul, 2013).

In a cartoon strip entitled Lat in London published in New Straits Times Press (NSTP) on 7 March 1975, Lat shares his worries of transforming into a big-city Westerner. It was drawn while Lat was in London. In this cartoon, Lat sketched it as he is writing a letter to his mother where he expressed his concern that he felt he is adopting urban British culture at the expense of the rural Malaysian roots he held dear. Lat also expressed his worries that he had disregarded some of his Malay customs and his Islamic faith. In the cartoons strips Lat narrated the activities that he considered as part of being “British”. The earlier four cartoon strips illustrate some scenes that are not endorsed by Malay culture and its interpretation of Islamic practice, such as drinking alcohol, and a close connection with dogs. However social and moral values in the Malaysia of the 1970’s were less conservative than those of today. Around the 1950’s to the end of the 1970’s Malaysian society was much more open with its social behaviour. In comparison to the present, it is inconceivable that cartoons such as this – showing a famous cartoonist drinking in defiance of his Islamic faith – would be authorized for publication, and it would be regarded as controversial leading to it being banned from publication.

In August 2009, this cartoon strip was republished in a compilation book Lat entitled Lat: Early Series through NSTP Groups, under the title London. The re-published version was changed though, with some of the cartoon panels taken out such as the one with the caption “and I drink in the pub standing up…”. This is not the only cartoon strip from Lat’s earliest series that has been erased from new re-publications. Several cartoons from Lat’s trips overseas such as to urban powerhouses like New York where Lat draws himself drinking and holding a can of beer, have been modified by erasing the beer can label from the cartoon. Thus apart from erasing the beer can label, some of the original cartoons from Lat documenting his exploration of big cities outside of Malaysia are actually being hidden from modern Malaysian society. It appears the kampung environment is in effect an easier one for the Malaysian government to deploy in promoting the nation, as there is less need to negotiate the liberalised or libertarian social behaviour perceived as being associated with modern city life.

Lat’s cartoons, though recalling his early rural life and contributing to an urban-focused popular vision of national identity, also mirrored Malaysian societal development through the years since the 1960’s. It is not too exaggerated to say that Lat’s cartoons are a form of visual evidence of how Malaysian society evolved. Because the cartoon is a form of visual documentation Lat’s work reflected the country’s political agenda and shifting social and religious mores. The 1979 Kampung Boy collection illustrates this facet of Lat’s work (see Figure 2). While it was a chance for Lat to record the memories of his village upbringing, the series of cartoons that were turned into a graphic novel (and re-published in the Arabic language in 2010) inadvertently documented a change in Malaysian societal attitudes, from progressive village community to modern but more conservative urban centres. The series is comprised of the visual images and icons of a rural Malay community based on Lat’s childhood experiences from the 1950’s to 1970’s. The nostalgic memories of the past, through traditional family manners, food, rural kampung surroundings, early school activities, and traditional past times, were documented mainly for the purpose of a visual records for his children when Lat started a family. It is also due to different lifestyles in urban areas that Lat was encouraged to capture the old kampung life.

Figure 2: The cover of Lat’s The Kampung Boy which depicts Malaysian rural life of the 1970s as experienced by the cartoonist (Mohammad Nor, 1979)

It is perhaps ironic and counter-intuitive that in Lat’s work the kampung represents a way of life that was more lax, pluralistic and less in ‘need’ of social regulation – whereas the Malaysian city is by the 21st century not so much monopolised by Western values as a place where Islamically inflected Western culture is prominent and able to be regulated. For example, in his black and white freestyle sketches, Lat recorded a change in Malaysian attitudes to women, particularly in rural areas. His series documented the activities that women are ‘allowed to do’ and through which women would be ‘accepted’ by others in public space around 1950’s Malaysia. Images were depicted of women’s berkemban (a batik sarong tied around midriff exposing areas of body such as shoulders and arms) which was traditionally used in rural kampung areas as the most comfortable outfit for domestic chores, hanging around the house, or bathing; and women smoking and dressed in fitted kebaya (traditional women’s blouse) with a batik sarong (traditional skirt). In Lat’s cartoons women are portrayed as confident, self-determination and expressive, and with sense of attitude. In both scenes, women are shown smoking, an image of women that is no longer seen in popular print media. Smoking for women is considered taboo in Malaysia and it has a strong association of being demeaning to women.

Discussion

In Malaysia’s city/country dialectic, the idea of the kampung or village has a strong hold over a modernising and highly regulated country, as a place of respite and retreat from an official nation-building agenda disseminated and implied through mainstream media. kampung imagery enjoys ongoing prominence in the oeuvre of Malaysia’s most influential cartoonist Lat, particularly in his autobiographical pictorial novels reflecting his rural and city experiences (kampung Boy and Town Boy). The kampung itself is constituted via the medium of Lat’s internationally famous cartoons to a global audience for whom the kampung does not have the immediate point of visceral recognition that it has for Malaysians.

The role of Lat – Malaysia’s godfather of cartooning and the quintessential kampung boy – in the documentation of this dichotomy is complex. In contrast to influential political satirists like Mark Knight from Australia, Jean Plantureux or Plantu from France, Graeme Mackay from Canada and Carl Giles in London, Lat declined to openly align himself with political commentary. In an interview with Eddie Campbell in an online portal by the publisher firstsecondbook, Lat instead sees his position as a historian of sorts, documenting the competing visions of rural and city Malaysia (Siegel, 2007):

I don’t think I am a political cartoonist because whenever I draw politicians the issues I touch on are very light humor…not deep enough….because politics don’t last….I prefer my drawings to last a longer life like in the Kampung Boy and Town Boy books.

It was on Lat’s return from his first trip to London that his profile rose and he became well known to Malaysians, locally and internationally. As Piyadasa (in Lat, 1994:48) stated,

Lat became a national celebrity almost overnight, gathering day by day an ever expending audience of ready admirers, drawn from the multi-racial English education readership of The New Straits Times.

This notion of Lat as an ubiquitous part of the Malaysian cultural psyche was also noted by one of the country’s prominent female journalists Adibah Amin, whose assessment of Lat’s popularity is described in her foreword for Lat 30 Years Later. “If a letter is to be addressed to Lat, it only has to state LAT, MALAYSIA, and it will arrive at the NSTP office.” This scenario demonstrated Lat as a key part of Malaysian life, whose popularity had travelled to every part of the country. As Amin wrote, Lat is the “unfailing source of delight to politicians and postmen, urbanite and kampung folk, old and young, simple and sophisticated” (in Lat, 1994:vii).

In many ways, Lat is a pro-government cartoonist. In comparison to Lat’s earlier series, his news cartoons are expressed in a voice that is unifying, while his narratives in reporting current issues are shaped by his own nationalist pride. Therefore even though in some of his cartoons he criticized current issues and mocked political attitudes and characters (as in the case of the Melayu Baru or New Malay concept), his cartoons have not been considered political but humorous, not having reached a level that will provoke discomfort among Malaysians. Lat’s role as a cartoonist in Malaysia was significantly expanded through branding and promoting the country’s nation-building activities, through national visual icons in his cartoons in order to integrate government policies on nation building in Malaysian society. Yet Lat’s fame is a globalised fame that can be read not just through a Western or orientalist lens but also through a universal undertone to some of his sentiments about the rural/urban dichotomy. The statements implied and explicitly explored through his imagery reflect how narrative and nostalgically based reflections upon modernisation and change have a poly-ethnic and transnational appeal.

Conclusion

Cartoonists occupy a strange space in Malaysia’s process of nation-building, and in the imagery it evokes whether it is the nostalgia of history and the life of the kampung or the irresistible urge to modernise and urbanise (Rahman 2012). Lat’s position as a Malaysian icon was nurtured by government agencies in the form of the state-run media that promoted his work (which in turn promoted national ideology). It was Lat’s humour as a unifying factor which allowed his work to be read as that of a chronicler of the key aspects of Malaysian history and national identity – dominated by the iconography of the kampung and the big city – instead of that of a political dissenter.

Azmi (2009: 19) describes Lat as “the Malaysian unifier”, whose work can be seen as the perfect agency by authority to keep the nation together. Apart from political flux, Lat is perceived as Malaysian catharsis, an icon that could represent and unite the different ‘Malaysias’ – rural, urban, Malay, Chinese, or Indian.

Wondrously, it comes very close in a person whom practically everyone has admired and embraced. In fact, he’s been inking art for two generations,

chronicling the nobility of community, prosper-thy-neighbour and the true Malaysian ideal: heartfelt humour, liberal, leg-pulling and a patriotism that is

subtle and endearing. Azmi (2009: 19)

The late Malaysian visual artist and art critic Redza Piyadasa wrote that Lat “was the right young man, at the right place, at the right time, to do the job” (Piyadasa, 1994:48). His job as a cartoonist at the New Straits Times required Lat to adopt a larger all-encompassing vision of his country than that which was normally expected of Malay cartoonists operating within strictly Malay-centred and parochial contexts. Piyadasa mentions the direction provided by the New Straits Times publisher, as “the emphasis was clearly on ‘Malaysian Life’ and he [Lat] had to project a more composite ‘Malaysian’ vision and identity” (ibid).

There are parts of Malaysia’s national history that have progressively been omitted and erased in the process of constructing national identity – for example, stories in relation to race, religion, gender and politics can easily be considered controversial subjects in Malaysian media and under Malaysian media laws, such stories are seen as sensitive issues not to be discussed in public, as it might cause a national threat (Anuar, 2005). In countries like Malaysia, because cartoons are perceived more as a form of entertainment rather then rebellious expression, flexibilities in expressing views through cartoons meant that some contentious topics usually bypassed the authorities’ attention. As Aznam (1989:42) put it:

If humour is the fine art of escape, Malaysian have unconsciously refined the art form…Malaysian laugh so they will not punch at each other. Humour allows Indians, Chinese and Malays to laugh at themselves so they will feel less the sting of others’ racial barbs. Here, humour is used to highlight stereotypes, and then to destroy them; to whittle away racial differences and reach a common, sympathetic cord.

It is due to this perception of cartooning as emotional, entertaining escapism that that cartoons are used and tolerated as a means to “cope with the stresses of multi-racial urban life” (1989:p.42). We would argue that in the case of Lat, they are also used as a medium to record the nostalgic memories of village life, a state-sanctioned charge towards urban-based modernity, and changing religious and social mores, in the process of shaping Malaysia’s national identity.

Works Cited

Ammirul, Adnan. 2013. “Tourism Malaysia takes local media on fam trip.” Brunei Times. Available at <http://www.bt.com.bn/happenings/2013/05/24/tourism-malaysia-takes-local-media-fam-trip>. Accessed September 17, 2013.

Anshar, Azmi. 2009. “Lat the Malaysian Unifier.” New Straits Times. May 03: 19.

Anuar, Mustafa K. 2005. “Journalism, national development and social justice in Malaysia.” In Asia Pacific Media Educator 1.16: 63-70.

Aznam, Suhaini. 1989. “Quipping Away at Racism.” Far Eastern Economic Review 146.50: 42.

Bamford, Anne and Andrew Francois. 2001. “Generating Meaning and Visualising Self: Graphic Symbolism and Interactive Online Cartoon.” Paper, presented at the Eighth International Literacy and Education Research Network Conference on Learning, Spetses, Greece, July 4-8.

Bujang, Rahmah Haji. 2005. “Continuity and Relevance of Malay Traditional Performance Art in this Millenium.” In Jurnal Pengajian Melayu, 15: 220-231.

Carstens, Sharon. 2005. Histories, cultures, identities: Studies in Malaysian Chinese worlds. Singapore: NUS Press.

Chong, Terence. 2006. “The Emerging Politics of Islam Hadhari.” In Malaysia: Recent Trends and Challenges, edited by Saw Swee-Hock and K. Kesavapany, pp. 26-46. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Chong, Terence. 2005. “The construction of the Malaysian Malay middle class: The Histories, intricacies and futures of the Melayu Baru.” In Social Identities 11.6: 573-587.

Edwards, Janis, and Carol Winkler. 1997. “Representative form and the visual ideograph: The Iwo Jima image in editorial cartoons.” In Quarterly Journal of Speech, 83.3: 289-310.

Hirschman, Charles. 1987. “The meaning and measurement of ethnicity in Malaysia: an analysis of census classifications.” In The Journal of Asian Studies, 46.3: 555-582.

Karim, Nor Shahriza Abdul, and Amelia Hasan. 2007. “Reading habits and attitude in the digital age: Analysis of gender and academic program differences in Malaysia.” In Electronic Library, 25.3: 285-298.

Lat. 1994. Lat 30 Years Later. Petaling Jaya: kampung Boy Sdn. Bhd.

Lent, John. 2003. “Cartooning in Malaysia and Singapore: The Same, but Different.” In International Journal of Comic Art, 5.1: 256–289.

Lent, John. 1999. “The Varied Drawing Lots of Lat, Malaysian Cartoonist.” In The Comics Journal 211: 35-39.

Lent, John. 1974. “Malaysia – Whose Mass Media are State Business.” In IPI Report, 11: 1-6.

Milne, Robert and Diane Mauzy. 1999. Malaysian Politics Under Mahathir. London and New York: Routledge.

Milner, Anthony. 2005. “Historians Writing Nations: Malaysian Contests.” In Nation-Building: Five Southeast Asian Histories, edited by Gungwu Wang, pp. 117-161. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Mohammad Nor, Khalid. 2003. Pameran Retrospektif Lat [Lat Retrospective Exhibition 1964–2003]. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: National Art Gallery.

Mohammad Nor, Khalid. 1979. The Kampung Boy. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Berita Publishing.

Muliyadi, Mahamood. 2004. The History of Malay Editorial Cartoons (1930s–1993). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Utusan Publications and Distributions.

New Straits Times. 2008. “Seeking laughter can be no joke after all.” New Straits Times. November 12.

Pandian, Ambigapathy. 1997. “Literacy in postcolonial Malaysia.” In Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 40.5: 402-404.

Piyadasa, Redza. 2003. “Lat the Cartoonist—An Appreciation”. Pameran Retrospektif Lat [Retrospective Exhibition 1964–2003]. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: National Art Gallery. Pp. 84–99

Provencher, Ronald, and Jaafar Omar. 1988. “Malay Humor Magazines as a Resource for the Study of Modern Malay Culture.” Sari, 6: 87-99.

Rahman, Zainurul Aniza Abd. 2012. Chronicling Fifty Years (1957-2007) of Malay-sian Identity (Doctoral dissertation). RMIT University, Melbourne.

Sandhu, Kernial Singh, and A. Mani. 1993. Indian Communities in Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Sanusi, Ahmad Abdullah, Norma Mansor, and Ahmad Abdul Kuddus. 2003. The Malaysian Bureaucracy: Four Decades of Development. Chicago: Pearson Malaysia.

Siegel, Mark. 2007. “Campbell Interviews Lat: Part 2.” Firstsecondbooks. Available at <http://firstsecondbooks.typepad.com/mainblog/2007/01/campbell_interv_1.html>. Accessed September 17, 2013.

Yip, Wai Fong, and Chin Huat Wong. 2010. “Lift Ban on Cartoons, Repeal PPPA.” The Nut Graph. Available at <http://www.thenutgraph.com/lift-ban-on-cartoons-repeal-pppa/>. Accessed September 16, 2013.

Author Bios

Dr. Nasya Bahfen is a senior lecturer in the School of Media, Film and Journalism at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

Contact email: nasya.bahfen@unsw.edu.au

Dr. Zainurul Aniza Abd Rahman is head of the Graphic Communication Department at the School of the Arts in University Sains Malaysia in Penang, Malaysia.

Contact email: zainurulrahman@usm.my

Dr Juliette Peers is a postgraduate supervisor and senior researcher in the School of Architecture and Design at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia.

Contact email: juliette.peers@rmit.edu.au