Picturing Performance Art: An exploration into the logic of performance documentation

Author: Tony Curran

Abstract

In the canon of western performance art it is those works that have been documented for posterity that are remembered in the canon of high art. For many performance artists it is the documentation of their work that has enabled them to be included in journals as well as historical surveys of performance art. This gives the documentation of the performance a profound importance as can be seen through the cases of relatively forgotten careers of many early performance artists who chose not to have their work documented.

This paper investigates the relationship between performance art and its residual documentation, looking specifically at different strategies that late modern and contemporary performance artists have used in order to document their works – from photography, video and drawing to ensure that the event can be preserved. From a survey of these approaches used by artists, this paper then discusses the documentation of the author’s own recent performance, undertaken over 33 days at the National Portrait Gallery in a work titled As Long As You’re Here (2013). In this performance, the artist, using an iPad, continuously drew participants who sat in the chair opposite for 33 consecutive days. Using software that recorded every mark made throughout the performance the work was then able to be exported as a video, which ran for 4 hours and 11 minutes and documents every observation the artist made throughout that sitting. The result is a non-photographic form of documentation – a hybrid drawing and video work.

The role that documentation plays in generating studio revenue is considered here, as limited edition prints of specific photographs selected by artists are often sold in commercial galleries in order to make the artists collectable and commodifiable in the global art market. Artists like Marina Abramovic exemplify this model, however there are other artists who seek to manage the authenticity and authorship over their documentation. For example, Carolee Schneeman painted over her documentary photographs, for her performance Interior Scroll (1975), in an expressionistic aesthetic ensuring that each print is a one-off image, authored with the hand of the artist. Conversely, Mike Parr has been shown to forego photographic and video documentation altogether in favour of drawing. His many drawing performances have blurred the lines between the relationships of performance to the larger traditions of image production and portraiture.

As Long As You’re Here offers a perverse perspective on performance art documentation by situating itself as both performance documentation and as a series of moving portraits. It is perverse in the sense that it blurs the boundaries between event-based dematerialized art practices such as performance art with traditional image based forms of art like portraiture. This paper concludes by suggesting that all performance, if documented, shares the common goal of figurative drawing, painting and photography. If this is true then it means that the image is no longer in service of the performance but rather, the artist performs so that the image can be made.

To cite this article

Curran, Tony. “Picturing Performance Art: An Exploration into the Logic of Performance Documentation.” Fusion Journal, no. 7, 2015.

Picturing Performance Art

There is a misconception within the contemporary artworld that images have become redundant since the emergence of performance art, immersive installations and new media art. Theorists of contemporary art, such as Terry Smith, have characterized contemporary art as a period in which artists are concerned with contemporaneity, that is the constantly unfolding present or nowness, or as Smith puts it “contemporary: the immediate, the contemporaneous, and the cotemporal.” (Smith, 4) These days the art event, performance or temporary exhibition, is valued by art institutions more than traditional forms of art such as individual drawings, paintings and sculptures produced in the artist’s studios. The contemporaneous, or the here and now, is antithetical to the image, which stands for a reality displaced from the here and now and represents something from the past, present or future that is absent, rather than present.

However what has emerged in this aesthetic climate of contemporaneity is a propensity to produce a certain kind of image – the photo documentation of the event-based artwork. This paper discusses the role of the photo document in event-based art looking specifically at performance art, installation and participatory artworks as a means to secure the artistic legitimacy of art events. A recent participatory project that I produced at the National Portrait Gallery, titled As Long As You’re Here (2013) tested the relationship between performance art and image culture and is discussed concomitantly to argue the case that: contemporary art continues to be governed by the aesthetics of the image, and does so within the poetic constraints of photography. This argument unveils a paradox that results from the ideals of contemporary art towards presence continuing to being anchored to an art market concerned with the sale of objects, and dependent on the circulation of images through the media.

As Long As You’re Here was a drawing performance lasting 33 consecutive days at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra during October and November of 2013. Located in the National Portrait Gallery’s (NPG) main atrium, Gordon Darling Hall, I sat with an iPad in one of two facing chairs ready to draw anyone who sat in the seat opposite me, to draw them for as long as they remained in that chair. Participants were in control of their final image by determining how long they participated and how still they were. There was only one rule – if the chair was empty, anyone could sit down in it for as long as they liked. I would continue to draw them for as long as they remained in the chair. Participants were, therefore, in control of the portrait process, dictating the length of their sittings, the style of their pose and by remaining still or by moving around. This allowed participants to directly influence the degree of verisimilitude and abstraction in the resulting portrait.

Each participant was emailed the image after it was completed and granted license to use the images as they chose. Giving participants license to use the images gave them the freedom to circulate their portrait online, print it for their home or to distribute to others. Rather than stipulating specific conditions on how they could use their image, the digital file was treated as shared property between them and myself. To the side of the chairs there was an LCD screen replaying a saved video of the digital drawing process from the previous days.

When people asked how to begin the sitting, my rehearsed response was that “There’s only one rule, if the chair is empty anyone can sit down for as long as they like.” Beyond that line participants tended to initiate conversation, often lasting the whole sitting or at other times reducing until the participant entered into a silent state of contemplation, rest or parallel activity such as reading, listening to music, or answering emails on their own mobile device. The final images show what occurred in the sitting.

Performance and Event-Art in Contemporary Art Institutions

As Long As You’re Here was a response to the event-based and performative nature that characterizes much of contemporary art. Contemporary art follows the post-war aesthetics of event-based and dematerialized arts including the arts of performance, happenings, environments, fluxus events, the extended situations in minimalism and the constructed situations in the French Situationist International group (Rush 217). As contemporary museums began to incorporate these forms of art into their programming they began to capitalize on the opportunities that these artforms offer institutions in growing audience attendance numbers (Burton 23). Associate Director of New York’s Whitney Museum, Johanna Burton describes this as institutions offering contemporary art as a form of entertainment. She writes:

Strikingly, more than one museum director has declared – on the record and with some pride – that the role of museums is shifting and that art must function like other forms of entertainment to retain any relevance. It must be crafted, that is, more to draw in crowds than to constitute a discursive realm. (Burton 22)

Art institutions increasingly aim to provide novel experiences for audiences at the expense of art that is anchored in material traditions. Helen Molesworth elaborates on this point, explaining that institutions’ concerns for collecting and preserving art objects have been replaced by a preoccupation for temporary works that promote audience participation in a search for an “ever-expanding audience”, which is “bound up with change and novelty (ie. temporary exhibitions) as opposed to stasis (the permanent collection)” (Molesworth 111-2). The dematerialized and participatory tack of contemporary art is corroborated by Rebentisch who describes the institutionalization of contemporary art as a form of “event culture” (Rebentisch 100). The dematerialisation of the art world could be read as a reaction against the excessive art market, however in a globalized world, Molesworth describes this as a “dependence on tourism”, which she explains is “increasingly itself a novelty-seeking form of behaviour” (Molesworth 113).

As Long As You’re Here tested the institutional demand for participatory programs as well as participation of individuals. The NPG’s willingness to program such a project supports the case that institutions value event-based participatory programming. Canberra’s ABC Radio presenter, Genevieve Jacobs, interviewed both the institution and a participant on why they chose to participate. Amanda Poland, Manager of Learning Programs at the NPG described the value of the project to the NPG:

When the proposal came to me from Tony about the project it seemed like a perfect alignment because drawing is really important we use drawing in all our learning programs here for school students. And having the experience of being a sitter is really a unique thing so often visitors come and look at the finished product and may never have been sitters themselves. So to think about the negotiated space between the artist and the sitter is really interesting and you know, I’ve sat a couple of times for Tony and I can see the dilemmas as a sitter, what you do, how you represent yourself, how you pose, and these are all the things we talk about with portraiture in the gallery. (Jacobs)

Participants actively tried to get the best portrait they could. When ABC journalist Genevieve Jacobs asked a participant why they chose to participate, he explained:

RAY: I wanted to have a portrait, um, to match my wife’s portrait, who she got painted by, I think it’s Xiaowen Chen that’s, I’m not sure about the pronunciation but when the portrait gallery first opened that was done so we thought that looked lonely so we’ll try and get one to put beside it.

JACOBS: You were well ensconced when I turned up, so you’ve been waiting for a bit.

RAY: I came this morning, but um, I knew I wouldn’t get in this morning. So I came back, I knew he was coming at two o’clock so I brought a book and sat in the chair.

JACOBS: Now Tony’s just been talking to me about how this becomes quite a collaborative process, the sitter and the artist. Is that how you’re thinking about this that you have a role to play?

RAY: Yes it worried me a little bit sitting still for a while, so I hope that Tony and I might interact a little bit otherwise I’m not sure how good a sitter I might be. (Jacobs)

Ray stayed for 3 hours for his portrait #162.

Photo Documentation

Despite the experiential and event-based nature of late-modern and contemporary art forms, history shows, as does the current artworld operations, that it is the documentary photograph that enables the event or performance to function as art. As Long As You’re Here subverted the photographic aesthetic by replacing the documentary photograph with documentary drawing.

The documentary photograph continues to ground artists within image culture or else run the risk of being excluded from the canon of art history. Artists working at the forefront of experiential forms of art, such as installation and performance, who did not document their work through photography struggle to have their contributions to the artworld recognized within the art historical canon. An example of such an artist is the Californian minimalist artist Robert Irwin. Irwin did not document his earlier installation work from the 1960s and as a result a great deal of his oeuvre can never enter the canon of late modern art. Irwin says that the art he’s made since the 1960s has been “an exploration of phenomenal presence,” (Weschler 66). Drawing on the philosophies of phenomenology Irwin’s work requires the viewer to be in the gallery to experience subtle perceptually uncanny phenomena, which reignites the viewer’s sense of perception and makes them aware of themselves as experiencing beings. Irwin’s works were explorations into presence despite the dominance of representations at that time in painting and drawing, and for this reason the artist refused any photography of his work until 1969 (Weschler xv). Irwin resisted photography because the camera could not convey the perceptual encounter with the work which had to be physically felt (Weschler 80). Or as Lawrence Weschler explained “a photograph could convey image but not presence,” (Weschler xv). After 1969 some of his more permanent works from that period have been photographed but many of the artist’s early temporary works have no documented trace. Without a reputation to attract large audiences, due to the early stage of Irwin’s career, his works were seen by few people.

The way that the image is used in contemporary art indicates that art remains in the throes of the image, as photograph, rather than in the dematerialized forms of performative art. The role and impact of photography in contemporary art has been compounded by the necessity of artists working in temporary forms such as participatory art to document their work in order to have their installations, events and performances included in media, catalogues, reviews and, ultimately, the canon of art history.

Tino Seghal is an interesting contemporary artist partly because his delegated performances are never documented. This is characteristic of Seghal whose work involves choreographed delegated performances – an artform which describes performance that is acted out by other individuals. On reviewing Seghal’s This is So Contemporary (2014) as part of the Kaldor Public Art Projects at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Andrew Frost writes about the extent to which photography was policed during a press preview:

At the press preview John Kaldor was personally making sure that curious members of the public didn’t take any photographs. One of Seghal’s instructions for the piece was that there be no recordings of the event – it is meant to be a special memory for us to cherish and not to be sullied in the public memory bank of social media. I was told that Sehgal doesn’t believe in unnecessary air travel and thus left the organization and execution of the constructed situation to a Sydney-based facilitator, and to Kaldor himself, who put his hand over the lens of a Chinese tourist’s camera, perhaps in an effort to maintain the purity of the event, or perhaps to honour the strict stipulation of the artist’s contract. (Frost)

Claire Bishop has interpreted Seghal’s ban on photographic documentation by linking the tradition of Seghal’s work to the instructional or score based work of the Fluxus artists who maintained that the score, a series of instructions like a musical score, is the original work of art and the performances are conducted by interpreters, hence the performances are not the works of art but are interpretations of the original work. According to Bishop, this “erodes any residual attachment to the idea of an original or ideal performance” (Bishop 224).

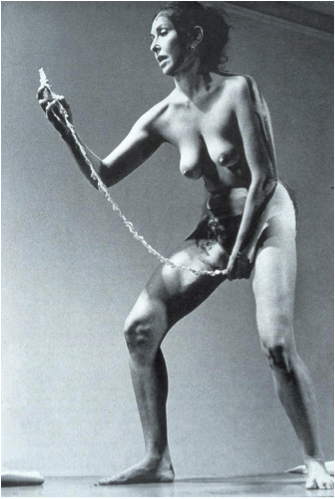

The photograph is now so important for contemporary art, however in many key works the photographer goes unacknowledged in art historical texts, such as Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll (1975). (Figure 1) Unlike photographers such as Joel Meyerowitz and Gianfranco Gorgoni who are credited for photographing Robert Irwin’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue (2000) (Figure 2) and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) (Figure 3), respectively, the photographer of Schneemann’s Interior Scroll goes unacknowledged in survey catalogues of contemporary art history and body art (Smith 41 and Warr 144). Nevertheless this image has become the iconic reading of Schneemann’s performance in later years and is the most recognizable moment of the performance.

Fantastical Documentation and the Link to Traditional Representation

The promotional uses of photo documentation follow the codes and conventions of romantic painting as an ideological anchor to seduce the viewer. Installation artists, such as Olafur Eliasson and James Turrell show how the documentation of the work can act as if it were a landscape painting to be appreciated for its own formal beauty within the tradition of landscape painting. In the documentation of works by Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson the figures appear in sublime landscapes calling upon the viewer to imagine themselves within a fantastical landscape. Eliasson’s installation shot for 360° room for all colours (2002) (Figure 4) shows a figure within an alien space.

Eliasson’s simulations of natural phenomena simultaneously act as simulations for the visitor of the installation and as studio sets for the production of an image. The figure in this installation as well as installations like The mediated motion (2001) (Figure 5) connote mysterious encounters where figures appear in misty landscapes, sometimes isolated or alternatively with a companion. The human figure in these landscapes introduces a potent element of narrative reminiscent of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the sea of fog (1818) (Figure 6) where the figure appears to the viewer as an imagined surrogate of themselves in the sublime grandeur of nature.

Eliasson’s images hail the viewer to imagine themselves walking within a fantastical landscape. Louis Althusser describes interpellation:

I shall then suggest that ideology ‘acts’ or ‘functions’ in such a way that it ‘recruits’ subjects (it transforms them all) by that very precise operation which I have called interpellation or hailing, and which can be imagined among the lines of the most commonplace everyday police (or other) hailing: ‘Hey, you there!’ (Althusser 162-3)

Eliasson would be no stranger to how this kind of imagery hails or interpellates the viewer in an Althusserian sense to imagine their own ‘adventure’ in the space depicted in the documentary photograph or ‘installation shot’. Through the anonymous subject, the image hails the viewer to imagine themselves within the depicted space. The use of the pronoun ‘You’ in his many exhibitions and artwork titles such as Take Your Time which travelled to Sydney’s MCA in 2010, or his artwork titles Your Sun Machine (1997), Your orange afterimage exposed (2000), Seeing yourself seeing (2001) support the view that this Eliasson uses these strategies to consistently hail his audience. (Grynsztejn 66)

Eliasson is not inexperienced with depicting the landscape through photographs, which he does as an early sketching phase in his process. The installation images that Eliasson produces are used in monographs and writings about his work and in promotional material, however part of the artist’s practice is in documenting the natural landscape through photographs which he also exhibits within his blockbuster survey shows. The aerial river series (2000) is a series of 42 photographs of rivers from an aerial perspective. Exhibited in a grid like structure this landscape photography is undoubtedly documentary in its mode of viewing and recalls a scientific precision of mapping, or a process of information or data gathering which may be used as sketches or studies to inform subsequent works (Grynsztejn 60). Comparing the documentary images of the natural landscape to the documentary photographs of the installation indicates the line Eliasson walks between documentation and image production – between fiction and reality.

Eliasson is most likely conscious of how his photographs mediate between reality and fantasy as he so regularly references the relationship between the natural and the artificial. Eliasson blurs the line between fiction and reality, phenomena and fantasy by deliberately leaving the mechanics of his installations exposed and allowing the viewer to see how their experience is mediated:

The point is that the museum in particular, and the world in general, try to communicate things as if they were real. And I try to show that there’s a much higher level of representation than first anticipated in a museum. So what we actually see isn’t real at all but artifice or illusion. (Birnbaum 9)

To follow Eliasson’s logic to its final conclusion the documentary images of nature are as ‘real’ as his simulations of nature in the gallery, and if we reverse this logic his simulations of nature are as unreal as his documentary photographs of nature. What Eliasson produces in both forms of ‘documentary’ is an effect impossible to document but must be produced in the viewer. Eliasson describes this as:

[A] subliminal border where suddenly your representational and your real position merge, and you see where you ‘really’ are, your own position. (Birnbaum 11)

Eliasson’s photographic documentation is a series of seductions. Nevertheless Eliasson’s images just like his installations are self confessing spectacles that seduce the viewer through a set of strategies of hailing and sensory stimulation provoking imagined and perhaps lived moments of sublime presence in a way that cannot be documented or demonstrated but must be experienced.

As Long As You’re Here aimed to capitalize on the kind of interpellation that Eliasson’s oeuvre demonstrates by using the conjoined pronoun You’re. The intent of this was to immediately address the person who read or heard the title, to function as an invitation that would uniquely hail individual members of the public.

Document, Image, Object and the Power of the Art Market

The question of authorship is at stake when the photograph of the performance lives on beyond the performance itself, particularly when artists seek to edition and sell the documentation as an art object for sale as is common practice for performance artists. Schneemann has overcome this issue by treating the photo document as a relic of the performance, which she altered by hand and sold as a unique object. By working over the top of the image in paint and her own urine, Carolee Schneemann re-authenticated the image as a work by the artist rather than by the photographer (Manchester). Nevertheless, the unaltered documentary photograph goes on to represent her performance Interior Scroll in the art historical canon simultaneously as the document of a Schneemann performance and a naked portrait photograph of Schneemann.

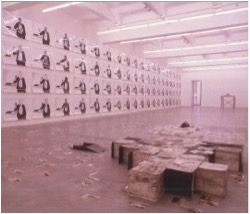

Schneemann’s approach to the photo document is one among many strategies employed by artists for working within the commercial art market. The photographic documentation often ends up on the art market for sale by performance artists and the commercial galleries who represent them. Australian artist Mike Parr, represented by Anna Schwartz gallery in Sydney and Melbourne has developed a practice in which he post-produces the residual images from his performance practice, remediating them to produce new drawings, photographs, installations and performances (Scheer 48). In his installation Photo Realism (1998) (Figure 7), Parr featured a mural of printed still images recorded from a performance of 100 Breaths (1992) (Figure 8), which as the author of one of Parr’s monographs, Edward Scheer, describes, “Parr sucks 100 etchings of his face onto his face before a camera.” (Scheer 71) The presence of the camera indicates that the performance is not intended to be a one off event but to be reactivated. Scheer explains further:

What was once documentation now becomes a site of reactivation of a body of work, a staged encounter that is not a repetition of the originating event but a re-presentation of it, which re-enacts an event for an audience that was neither spatially nor temporally connected to it. (Scheer 116)

Alternatively an artist might follow the example of Yugoslavian and New York-based performance artist Marina Abramović, who editions a limited number of photographic prints from her performance documentation to be sold as art objects in the commercial art market (Aker, Dupre and Chermayeff). The sale of the documentary images of her performances indicates that performance artists are in the business of crafting images.

The Authenticity of Presence

The documentation of performance and event-based art is a means for artists to prove that the work was successful in accumulating value through the institutional currency of audience participation. However such transparent efforts to attract large numbers of participants and to document those participants threatens the aesthetic ideals of presence in these contemporary art forms, resulting in heavily mediated works of art. Once the demand for participation becomes too high the work becomes spectacularised, and this can be seen as a major point of derision in contemporary aesthetic theory.

Artists and institutions that claim the authenticity of presence can only present an illusion of presence because of the inherently mediated nature of a gallery and constructed event. The idea of presence was taken most literally in 2010 by Serbian-born performance artist Marina Abramović in her performance retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art titled The Artist is Present. Abramović’s exhibition and the new work featured within attracted criticism around the potential of presence in gallery exhibitions. These criticisms serve as a useful case study for contemporary art’s paradoxical fetishes for spectacle and authentic presence.

Marina Abramović’s retrospective was fraught by explicitly claiming presence for her work. The exhibition featured reperformances of Abramović’s earlier works in her solo career but also her performances with former partner and collaborator Ulay as well as video and photographic documentation of the original performances. In addition to the retrospective exhibition, Abramović created a new work, which was developed out of the title of her retrospective. For this new work, the artist was literally present for viewers to come and sit with her and meet her gaze for as long as they like. The exhibition The Artist is Present, curated by Klaus Biedenbach, ran for three months at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and for the duration of that exhibition Marina Abramović performed her new work with the same title. Abramović now in her sixties had developed a prominent career anchoring her oeuvre within the canon of performance art and has attracted substantial following within the artworld. Every day for three months, Abramović sat in her chair located in the centre of a gallery space, meeting the gazes of the people who sat opposite her.

Art historian Caroline Jones argues that the concept of presence was undermined throughout Abramović’s exhibition at MoMA. She says:

The Artist is Present has only a fractional relation to the fetish of presence. The experience of the intersubjective gaze, admittedly compelling, is consistently bracketed through photo releases you must sign, through three “live” webcams, through the Italian photographer making a book of the piece, and not least from the picture-snapping visitors surrounding the spotlighted atrium – in short, by the overwhelming apparatus of the document that [Tino] Seghal has problematised. The Artist is Present inserts the visitor into an intensely mediated and surveilled art activity; one’s production of performatives is compromised, to say the least. (Jones 218)

The authenticity of the participation and presence within the project is questionable in the sense that individuals had behavioural or disciplinary limitations placed upon them. Participants were required not to talk, not to touch the artist, to meet the artist’s gaze until they were ready to end their sitting in which case they were asked to signal by bowing their head (Akers and Dupre). This can be attributed to the level of celebrity of the late career performance artist and the popularity of the museum. Both of these factors contributed to large crowds and hence a strict and arguably oppressive regime of security and crowd control dissolving the audience’s capacity for presence. Akers’ documentary film shows footage of two individuals whose sittings were intervened by security guards because one participant covered their face with a picture and the other participant removed their clothes before attempting to sit down. The latter participant claimed that she was not informed that she couldn’t strip and regretted that she was not allowed to sit for Abramović. In tears she said to Akers’ camera operator:

I didn’t know it was a rule, I didn’t realize and I would have obviously obeyed the rule if I had known but I wanted it to be spontaneous, I didn’t want anybody to know, you know, I wanted it to be its own thing and to be special with her and I thought in that space, in that square, you get your own, its like the audience part of the art, and, and, you bring to it, and I just wanted to be as vulnerable to her as she makes herself to everyone else. (Akers and Dupre)

This mediation indicated as much sensitivity for the future or afterlife of the project as it did for the present participation of the audience members.

The mediated nature of The Artist is Present is better contextualized as a photographic studio, or in the artist’s own words, “How I imagine Artist is Present is, I actually, imagine a more like a kind of film set. There is a huge square of lights” (Akers and Dupre). In Akers’ documentary of Abramović she is shown walking through the Museum of Modern Art with a digital camera, planning the work as an event to be photographed.

The Artist is Present culminated in a series of portraits taken by photographer-cum-collaborator Marco Anelli indicating that the artist was knowingly creating a photographic studio set-up with crowd sourced subjects. In watching Akers’s documentary film it is evident that Abramović’s performance is knowingly directed towards producing performance ‘documents’ or, otherwise considered, image objects (Akers and Dupre).

The artwork lives on in book form, DVD documentary and social media photo galleries. After the performance, the official photographs of the event were uploaded onto MoMA’s flickr page, an online social media photo gallery site 1 . The composition of these images is a standard three quarter profile view with a narrow depth of focus, which turns the background of the shot into a blurred wash. The background of each subject is a soft patternation of colour and tone as different people milling around behind the participant shifted and changed with different kinds of clothing – the visual environment constantly in flux leaving each composition unique. The lack of focus on the background emphasizes the rhetoric of the documentation in line with the performance. In front of Abramović you are the only person who exists – a special individual in a transcendental moment of time. Participants who were featured in the exhibition could go back to the gallery and view their portrait. Anelli has since published his collection of portraits in a book titled Portraits in the Presence of Marina Abramović (Anelli). The portraits are a single shot of each of the 1,545 sittings with the duration of their sitting labeled with the image.

Abramović’s performance proves that contemporaneity and presence are undermined by the inherent mediation of art and the artworld and its embeddedness within images and image culture. What Abramović’s work highlights is the paradox in the rhetoric of contemporaneity and presence as a mark of art’s authenticity and the constant demands for some kind of image outcome – that the artist continues to be a producer of images. In contemporary art, in what is often referred to as a post-medium condition, the images that are produced continue to be of the same medium – that is that they are made with a camera.

As Long As You’re Here responded to the criticisms aimed at The Artist is Present. It did so using strategies such as hosting the project at a major national institution, Australia’s National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, by dissolving the need for a contracts and photo-releases, and through a self-governing form of crowd control. The design of the interaction elegantly managed any issues to do with crowd control without needing the assistance of gallery attendants, which were a powerful and repressive force in the operations of The Artist is Present. The one rule that, if the chair was empty anyone could sit for as long as they wished, allowed the project to escape the aesthetic disturbance of consent forms and the mediation of the relationship that such forms have. A large sign explained to any approaching individual about the project that:

Artist Tony Curran invites you to ‘sit’ for him, for as long as you like, while he paints your portrait using his iPad. You can request the artist to email the portrait.

While it was not my idea to upload the portraits onto the photo sharing social media platform Flickr, the NPG’s decision to do so fortunately mirrored the online presence of The Artist is Present on MoMA’s Flickr page. The NPG already had an established Flickr account on which it uploaded photographs of events and gallery programs as a form of online public engagement. At the time of writing these drawings are still viewable on the NPG’s Flickr page in the album named As Long As You Are Here. Similarly, MoMA posted Marco Anelli’s portraits of sitters on Flickr enabling users to view and share the images easily across social media platforms.

Galleries and museums have begun to adopt liberal approaches to photography within their exhibitions after having seen the potential for free publicity from exhibition attendees sharing photos on social media. Institutions now increasingly capitalize on the public’s use of online hashtags or linked keywords for users to attach to their photographs so that the galleries can listen in and collect information from online conversations about their shows. Searching for ‘#poptopopism’ on popular social media platform Instagram produces thousands of audience photographs on instagram of the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s Pop Art Exhibition Pop to Popism (2014-15). Inventing hashtags has become an important feature in marketing campaigns for Museums and Galleries with institutions seeking unique phrases to direct audiences to facilitate this easy quantification – hence the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s hash tag #closetochuck for their exhibition Chuck Close: Prints, Process and Collaboration (2014-15)

The circulation of exhibition and event documents through social media adds real world value by being a form of publicity for the gallery as well as by generating quantifiable data, which institutions can use to demonstrate audience engagement to funding bodies. In response to social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram institutions have begun to take a more relaxed approach to photography in the gallery. The potential for monetization of social media photography signals a return to the image as a major aesthetic force in contemporary art (Oudyn, Gordon and Elliott).

Viewers of Anish Kapoor’s Sydney exhibition engaged with the work by taking ‘selfies’, photographs of themselves, reflected in the distorted mirrors, S-Curve (2006) (Figure 9) and C-Curve (2007). These works provided audience members with an opportunity to create novel images for their social media feeds, which in turn expanded the marketing reach of the exhibition. The amount of ‘selfies’ and pictures of friends that have graced social media under the hash tag of #anishkapoor at the time of writing is over 25,000. The rise of gallery selfies is evidence of the fact that figurative pictures are re-emerging, with a force, as an essential aesthetic of the museum show.

Contemporary artists still have to make images whether it is outsourced to gallery audience prosumers or not. The diversity of strategies that artists have employed in relation to their photo documents reveals the centrality of photography within the aesthetics of contemporary art.

Stuck with Photography but Drawing a Way Out

The ‘return to the image’ discussed so far has been primarily concerned with a return to the photographic image, however As Long As You’re Here culminated in drawings rather than photographs. The reason that many of the examples discussed so far have been photographic, is due to the fact that early forms of performance and event-based art were about presence, however subsequent artists have foregone the ideal of presence for the construction of images which helped to promote the artists’ career opportunities, indicating a crisis in the rhetoric of contemporaneity. Susan Sontag observed in her seminal text On Photography (1973), “Now all art aspires to the condition of photography” (Sontag 117).

The ‘genius’ of photography that Roland Barthes famously described in 1982 convinced the viewer that photography had the capacity to persuade viewers of the truth of the pictorial content:

… I henceforth placed the nature – the genius – of photography, since no painted portrait, supposing that it seemed “true” to me, could compel me to believe its referent had really existed. (Barthes 77)

The previous examples discussed, however testify to the ideological and rhetorical bent of documentary photography, particularly within the artworld architectures. Recently the camera’s capacity to capture event of performance has come under question. In the 1980s, Australian performance artist Mike Parr became aware of the intrusion of photographic aesthetics on the ideals of performance as an artform of duration and physical presence. Photo documentation resulted, according to Parr, in the “photo-death” of the event or subject captured. To capture the event as an image was to freeze it and kill the very thing that made performance an aesthetic of duration and phenomenological presence. On Parr’s concept of photo-death, art historian Edward Scheer has written, “when the focus of the act is to capture the moment, the moment is of course lost” (Scheer 40).

Much of Mike Parr’s practice has been a response to this idea of photo-death. Scheer has referred to Parr’s practice as:

[Attempting] to encode a self-critique (of the event of performance) within their content and … to contain their own end – the passing of performance into documentation and memory – within their structures. (Scheer 115)

Since the 1980s Parr has actively incorporated drawing into his performances as the documentation, aftermath or residue of the performances. Beginning by redrawing his photographic documentation in the Parapraxis series beginning in 1981 (Figure 10), Parr began to use drawing as a trace of performative activity, letting the marks indicate gesture and time (Scheer 41). Continually re-mediating these residues, whether they’re prints, photographs, drawings or Xerox copies, Parr continued to post-produce this documentation as new performances and art objects for collection. One example of Parr’s performance drawing is A-Artaud (Against the Light) Self Portrait at Sixty Five, (1983) (Figure 11). In this work the relic or residue of the performance process is a drawn image rather than a photographic image. The drawn image is more easily readable as an art object and as well as integrating performance practice into a ready art market through collection Parr also identifies a documentary realism of drawing as a temporal gestural image as distinct from the fraction of a second that characterizes photographic documentation.

Mike Parr’s use of drawing as a trace of a performative process not only questions photography’s appropriateness as a documentary apparatus for performance, but it also raises the question – if Abramović’s performance ultimately results in a series of photographic portraits, what is the difference between her project and the efforts of portrait painters? The life painting sittings of an artist such as Lucian Freud is a useful parallel to the relational and performative aspirations of Abramović in her MoMA spectacular. Martin Gayford’s book, Man with a Blue Scarf (2010) is a perfect example of how the portrait involves event-based, performative and intersubjective dynamics described in Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics. Gayford’s book is a diaristic account of the relationship that develops between the author and the British painter Lucian Freud while Gayford sits for a portrait. Gayford discusses not just how Freud handles the paint or how he sets up the model, but how Freud handles the social relationship between himself and his model. Gayford explains that it is through interaction with the sitter that the portraitist learns about his model, how his facial muscles work and how they respond in conversation, Gayford reports that “the artist must interact with the sitter,” in order to see how the facial muscles work and to see the facial expressions (Gayford 21). The situation of the portrait sets up an aesthetic and social experience for the participant, the painted portrait bearing a striking resemblance to the documentation of that intersubjective encounter.

The physical presence of the subject provides the artist with a greater amount of time to observe the subject as a temporal being with changing states of awareness, expressions and movements. While Lucian Freud painted Martin Gayford in Man With a Blue Scarf (2004) (Figure 12), Gayford used the sitting as an opportunity to learn about Freud so that he could publish a written portrait or biography of the painter, Freud, from all the hours that they had spent together (21). One of Gayford’s primary praises of the work of Freud is the extent to which the artist observes his sitter. Gayford explains that time is an essential element of the painting and describes the value of this temporal plethora of observation:

[A] painter such as LF – who spends hours, months, even years observing his subject – quite naturally records vastly more information than a camera lens can see. It is thus a matter of accumulated experience: that is memory. The reason why everybody sees differently is that each of us perceives a given sight from the vantage point of their own past thoughts and feelings. (Gayfrod 116)

Presence provides a valuable mode of realism for the viewer through ‘layered time’. After Freud finished his painting of fellow artist David Hockney, Gayford quoted Hockney as explaining “the painting of him by LF has over a hundred hours ‘layered into it’, and with them innumerable visual sensations and thoughts” (Gayford 145). ‘Layering time’ in the way described in Freud’s painting implies an alternative mode of realism deviating from photographic realism. Here both Gayford and Hockney explain that there is more information, more sensation and more interpretation of the subject by the artist whenever layered time is used.

‘Layering time’ is more visually interesting than a frozen moment in time. To understand this properly, the work of David Hockney after 1972 is instructive. Hockney discovered while making his painting Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures) (1972) (Figure 13) that if he made a joiner photograph using several photographs of the one figure that the figure would have a greater visual intensity due to the range of perspectives offered of that figure. Hockney guessed that because the photograph is only a fraction of a second, it only demands a fraction of a second of the viewer’s attention, however by collaring five different pictures of the same figure Hockney believed that the viewer was likely to spend five times longer looking at the figure (Featherstone). Hockney went on to produce a large number of joiner photograph pictures to demonstrate this point.

David Hockney’s joiner portrait of a couple doing a crossword together in The Crossword Puzzle (1983) (Figure 14) also shows the potential for layered time in portraiture. Hockney describes his work:

I think probably the first picture was taken when she was almost ready to write the word and then as she got more excited thinking the word is correct she moves down. It starts with the top of her head and ends with the tip of her pen. And I realized you could make portraits more and more complex, showing different expressions on the face, using the passing of time and it opened up enormous possibilities. (Featherstone)

Hockney refers to the process of collaging the individual snapshots into a joiner photograph as a process of drawing (Featherstone). What Hockney identifies through these is the amount of time spent on the work as a visible element of the work and the necessity to extend the time of pictures beyond the fraction of a second that photography characteristically represents, heightening the degree of documentary information that can be shown while increasing the visual interest of the image for the viewer.

Considering drawing as documentation, as Parr has done, the portrait sitting could be considered much like the relational and performative work of Marina Abramović’s The Artist is Present, with the exception that Abramović staged her work publically, whereas Freud worked with the sitter privately in his studio.

As Long As You’re Here tested the relationship between the event-based work and the tradition of portraiture by relocating the portrait sitting, which usually takes place in the studio and placing it on public display, inviting people to ‘participate’. Doing so perverted the usual relationship between the contemporary artwork as event and its residual documentation while perverting the tradition of portraiture by foregrounding its event status at the expense of the status of the final portrait image. If the art event culminates in an image then the event of portraiture is the sitting and the portrait is the documentation of that event. To execute this, the drawings were made on a recent technological innovation, an iPad, that allowed for the technology to be portable, clean, easy to draw with and simple to disseminate the portraits to participants and on social media.

Drawing as Documentation

The documentation of As Long As You’re Here is in the drawings themselves. Although there was no ban on photography and journalists took photographs to include in their news stories (Figure 15), the project is documented through the drawings. Unlike other forms of event-based practice, the documentation of As Long As You’re Here is thus to be found in the drawn portraits themselves. Rather than the obligatory installation shot that characterizes much of modern and contemporary art, As Long As You’re Here produced its own documentation in the form of digital drawings as still images and in video. As such the documentation was embedded into the central activity of the work – drawing the subject.

The drawings were made using an application called Brushes, an App that had an in-built feature that automatically saves every brushstroke made in the sitting so that it could be saved as a video. The video playback function of Brushes was a crucial part of As Long As You’re Here because it took the pressure off the ‘finished’ image and acted more as a record of the sitting. In Brushes the drawings were made on two layers, a background layer which built up while there were no participants and a subject layer. This two-layered process meant that the figure layer could be completely erased at the end of every sitting to create a fresh new background for the next participant without losing the image of the previous figure, which was recorded within the video.

While the project resulted in 194 portraits of participants, there was also a four-hour video time-lapse of the whole drawing process, showing participant’s changing positions and indicating the amount of time that they sat for me. The video play-back of the previous days equated to approximately one and a half minutes of video, a sped up time lapse of about one hour’s worth of drawing meaning that the actual artwork can be used as a recording measure, not just of the numbers of participants but also the duration of their sitting, how much they moved and how many times they participated. Subjects who sat for a long time had fuller, more developed portraits than those that sat for less time. #18 (Figure 16) from the series shows the results of a relatively short sitting, whereas #144 (Figure 17) shows a more developed result from about a two-hour sitting. In addition #44 (Figure 18) and #10 (Figure 19) show the difference between subjects making themselves visible as in #10, versus being represented as moving targets in #44. The position of the child in #44 has shifted dramatically throughout the sitting as can be read in the drawing as having laid over the mother’s lap, having sat on the mother’s lap, and having placed her white soft toy lamb in different spots throughout the sitting showing a temporal reading of the abstract fragments of information. #10 shows an older woman in a more reflective pose. Neither images show a frozen moment or a slice of time, but both differently portray time as it unfolded in the sitting with the energetic child literally ‘all over the place’ within the picture, and the more senior lady firmly placed in the seat.

The new technology of the touch screen provides a method of drawing, which capitalizes on the layered time described by Gayford and Hockney. This drawing method increases the subject’s agency through its portability and capacity to save every step of the drawing process, allowing the subject to move freely. As a result, photo-death was overcome by the aesthetics of flux.

The relationship between the representational arts of drawing and painting and the contemporary event-based arts of performance and installation is one of porosity. This paper has argued that the ideal of contemporaneity is corrupted by the artworld architectures. These architectures simultaneously demand that artists present themselves as sophisticated examples of event-based art and reward only those artists who continue to contradict this ideal through a representational regime of art, dominated by photography. As Long As You’re Here aimed to expose this contradiction by emphasizing clearly the relationship between contemporary modes of art practice, such as performance and participatory arts, and one of the oldest forms of visual art, the drawn portrait.

Bibliography

Anelli, Marco. Portraits in the Presence of Marina Abramovic. Bologna: Damiani, 2012.

Marina Abramovic: The Artist Is Present. Directors Matthew Akers and Jeff Dupre. 2012. DVD.

Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes toward an Investigation).” Trans. Brewster, Ben. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. Ed. Althusser, Louis. London: NLB, 1971. 121-173.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. Trans. Howard, Richard. London: Vintage, Random House, 1981.

Birnbaum, Daniel. “Attension Universe: The Work of Olafur Eliasson.” Olafur Eliasson. Eds. Madeleine Grynsztejn, Daniel Birnbaum and Michael Speaks. London: Phaidon Press, 2002. 8-33.

Bishop, Claire. Articifical Hells: Participation and the Politics of Spectatorship. New York: Verso, 2012.

Burton, Johanna. “A Questionnaire on ‘the Contemporary’: 32 Responses.” October 130. Fall (2009): 22-24.

David Hockney: Joiner Photographs. 1983. Film. Evans, Nick and Featherstone, Don. 1983.

Frost, Andrew. “Tino Sehgal: This Is So Contemporary – Review.” The Guardian. 6 February, 2014.

Gayford, Martin. Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud. London: Thames and Hudson, 2010.

Grynsztejn, Madeleine. “Attension Universe: The Work of Olafur Eliasson.” Olafur Eliasson. Ed. Madeleine Grynsztejn, Daniel Birnbaum and Michael Speaks. London: Phaidon Press, 2002. 36-95.

Jacobs, Genevieve. “Portraiture: As Simple as Taking a Tablet.” ABC Canberra 2013. Web. 14/2/2014.

Jones, Caroline. “Staged Presence (Vol 48, Pg 214, 2009).” Artforum International 48.10 (2010): 375-75.

Manchester, Elizabeth. “Carolee Schneemann Interior Scroll 1975 ” TATE 2003. Web. Februrary 22, 2015.

Molesworth, Helen. “A Questionnaire on ‘the Contemporary’: 32 Responses.” October 130. Fall (2009): 111-116.

Rebentisch, Juliane. “A Questionnaire on ‘the Contemporary’: 32 Responses.” October 130. Fall (2009): 100-103.

Rush, Michael. New Media in Art. (World of Art.) (2nd. Ed). London: Thames and Hudson, 2005.

Scheer, Edward. The Infinity Machine: Mike Parr’s Performance Art 1971-2005. Melbourne: Melbourne: Schwartz Media,, 2009.

Smith, Terry. What Is Contemporary Art? Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Rosetta Books, 1973.

Oudyn, Tamara, Taylor, Gordon and Elliott, Simon. Photo Gallery: Rule Change: It’s One of the Last Galleries in the World With a Photography Ban, but Now the National Gallery in Canberra Is Playing Catch-Up. 2014.

Warr, Tracey. “Works.” The Artist’s Body. NY, New York: Phaidon Press, 2000. 48-189.

Weschler, Lawrence. Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees. Expanded Edition. CA: University of California Press, 2008.

Figure 2. Robert Irwin (b. 1928)

Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue?, 2006

Linear polyurethane paint on 6 aircraft honeycomb aluminum rectangles, overall installed: 315 x 1600 x 660cm. Aluminum rectangles: 480 x 660cm each.

Pace Gallery

Photo credit: Joel Meyerowitz

Figure 3. Robert Smithson (b. 1938)

Spiral Jetty, 1970

Mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks and water. Rozel Point, Box Elder County, Utah 4.6 m x 460.0 m

City of Utah

Photo credit: Gianfranco Gorgoni

Figure 4. Olafur Eliasson (b. 1967)

360° room for all colours, 2002

Stainless steel, projection foil, fluorescent lights, wood and control unit.

Musée d´Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 2002

Figure 5. Olafur Eliasson

The mediated motion, 2001

Water, wood, compressed soil, fog machine, metal, foil, Lemna minor (duckweed), and Lentinula edodes (shiitake mushrooms)

Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria, 2001

Photo: Markus Tretter

Figure 6. Caspar David Friedrich (1774 – 1840)

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818

Oil-on-canvas, 98.4 cm × 74.8 cm

Kunsthalle Hamburg, Germany

Figure 7. Mike Parr (b. 1948)

Photo Realism (Shanty Town), 1998

Installation

Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne

Figure 8. Mike Parr (b. 1948)

100 Breaths, 1992.

Performance, 100 self portraits on A4 sheets of copper. Exhibited by breathing each sheet directly onto his face

Figure 9. Anish Kapoor (b. 1954)

S-Curve, 2006

Stainless steel 216.5 × 975.4 × 121.9cm

Photograph: Joshua White, Los Angeles

![Figure 10. Mike Parr (b. 1948) Parapraxis 111: [Cold Photography] Menippean Discourse as the Garments of the Moon [Interaction with my Mother], 1982 eight Cibachrome photographs bonded onto aluminium sheeting, 8 photographs: each 158.0 x 106.0 cm image/sheet; 316.0 x 424.0 cm installed. Art Gallery of New South Wales](http://fusion-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Curran-Figure-10.jpg)

Figure 10. Mike Parr (b. 1948)

Parapraxis 111: [Cold Photography] Menippean Discourse as the Garments of the Moon [Interaction with my Mother], 1982

eight Cibachrome photographs bonded onto aluminium sheeting, 8 photographs: each 158.0 x 106.0 cm image/sheet; 316.0 x 424.0 cm installed.

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Figure 11. Mike Parr (b. 1945)

A-Artaud (Against the Light) Self Portrait at 65 (detail), 1983

Installation at the Art Gallery of Western Australia

Figure 12. Lucian Freud (1922 – 2011)

Man with a Blue Scarf, 2004

Oil on canvas, 66 x 50.8 cm

Collection Frances F. Bowes

Figure 13. David Hockney (b. 1937)

Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), 1972

Acrylic on canvas, 214 x 305 cm

Private Collection

Figure 14. David Hockney (b. 1937)

The Crossword Puzzle, Minneapolis, January 1983, 1983

Photocollage, 83.8 x 116.8 cm Private collection

Figure 15. Tony Curran (b. 1984)

As Long As You’re Here, 2013

Performance, 33 days duration

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

Photo credit: Rohan Thomson

Figure 16. Tony Curran (b. 1984)

As Long As You’re Here #18, 2013

Digital drawing, 2048 x 1536px

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

Figure 17. Tony Curran (b. 1984)

As Long As You’re Here #18, 2013

Digital drawing, 2048 x 1536px

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

Figure 18. Tony Curran (b. 1984)

As Long As You’re Here #44, 2013

Digital drawing, 2048 x 1536px

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

Figure 19. Tony Curran (b. 1984) As Long As You’re Here #10, 2013 Digital drawing, 2048 x 1536px National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

About the Author

Dr Tony Curran is a practicing artist and researcher exploring at the relationship between digital drawing and forms of contemporary figurative painting. Curran holds a PhD in Fine Art from Charles Sturt University and is a sessional academic in Painting at the Australian National University School of Art as well as Art History, Media Arts and Drawing at Charles Sturt University. His work has been shown at the National Portrait Gallery, the University of Edinburgh, S. H Ervin Gallery and the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/themuseumofmodernart/sets/72157623741486824/ ↩