The Land of the Lyrebird and the Queen’s Colony 2020

Louisa Waters

Full text | PDF

Abstract

My creative practice research over the past four years has critiqued the transformation of Gunnai land since colonisation, through narratives of fire, critiquing European anthropogenic fire regimes.

As a white coloniser who has lived on Gunnai land most of her life, I am familiar with dominant fire narratives within popular discourse. Drawing on teachings from Wayne Thorpe, Gunnai Custodian, Storyteller, linguist and teacher, assisted in de-stabilising these narratives and augmented my understanding of the significance of the-more-than human world and other “players” within the ecosystems we are contingent upon.

One of the most significant players who emerged from our conversations was the lyrebird. The lyrebird story exposed me to rich textual material and new bodies of knowledge that spanned archival, scientific and critical enquiry. By exploring narratives of fire through the lyrebird story, I imagined a voice outside the anthropocentric lens, one which could bear witness and be a counter voice to dominant coloniser – moreover a voice which could urge us to consider the-more-than human world so critically afflicted by the colonial project and the Anthropocene.

Keywords

Anthropocene, anthropogenic fire, lyrebird, colonisation.

Enter the Lyrebird: Playing their Part

They miss out on the natural land managers, the birds and animals. Gippsland was known as “the land of the lyrebird.” The lyrebird’s job is to rake up so many tonnes per year of leaf litter, clearing the undergrowth from growing too much. So, you’ve got canopies that keeps the coolness and protects it from drying out. All the birds and animals have got their jobs to do. The plants have their jobs to do, but once they’re cleared and the odds are against them, well then the place dries out and you create a fire-prone country.

Wayne Thorpe (2018)

Playing the Part

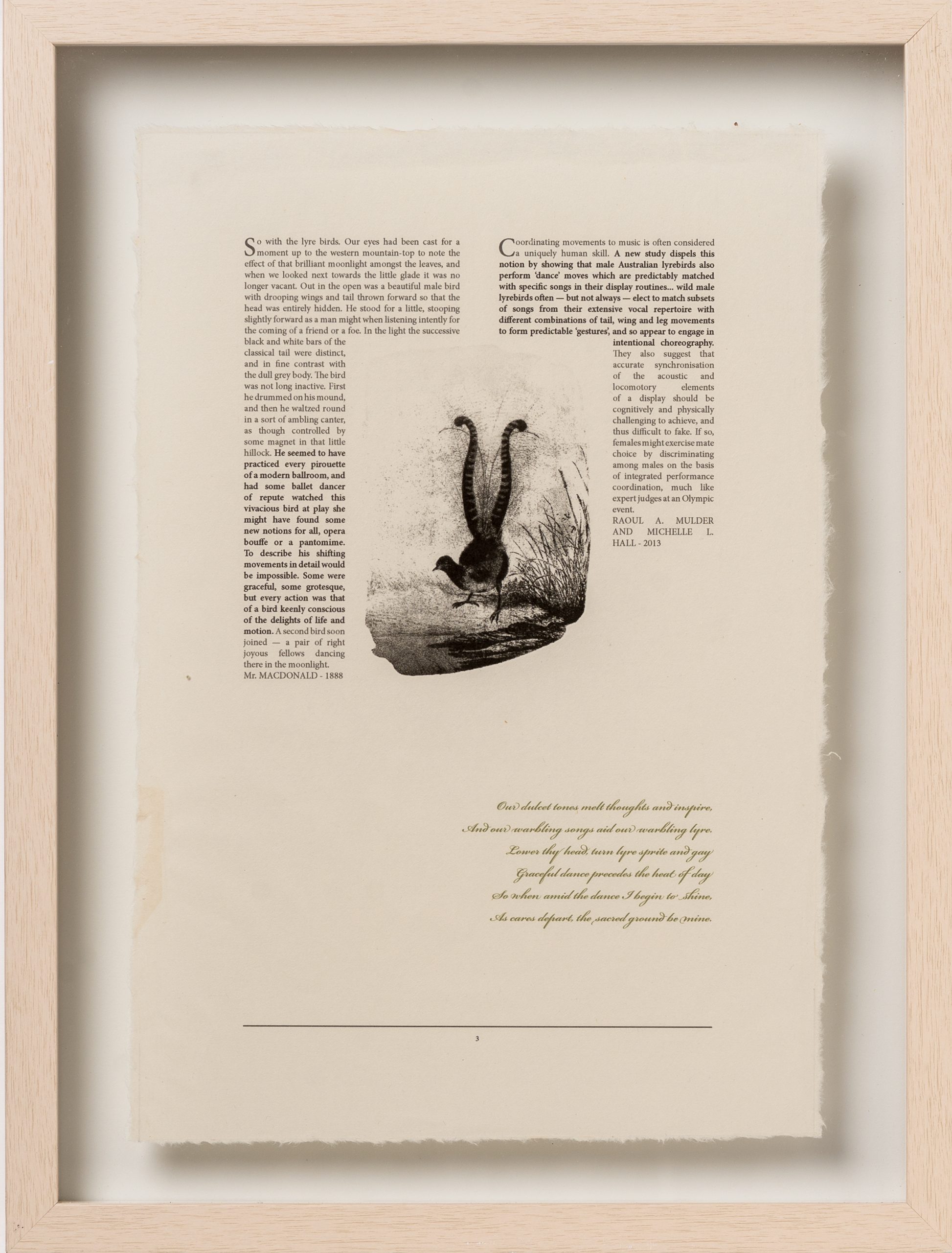

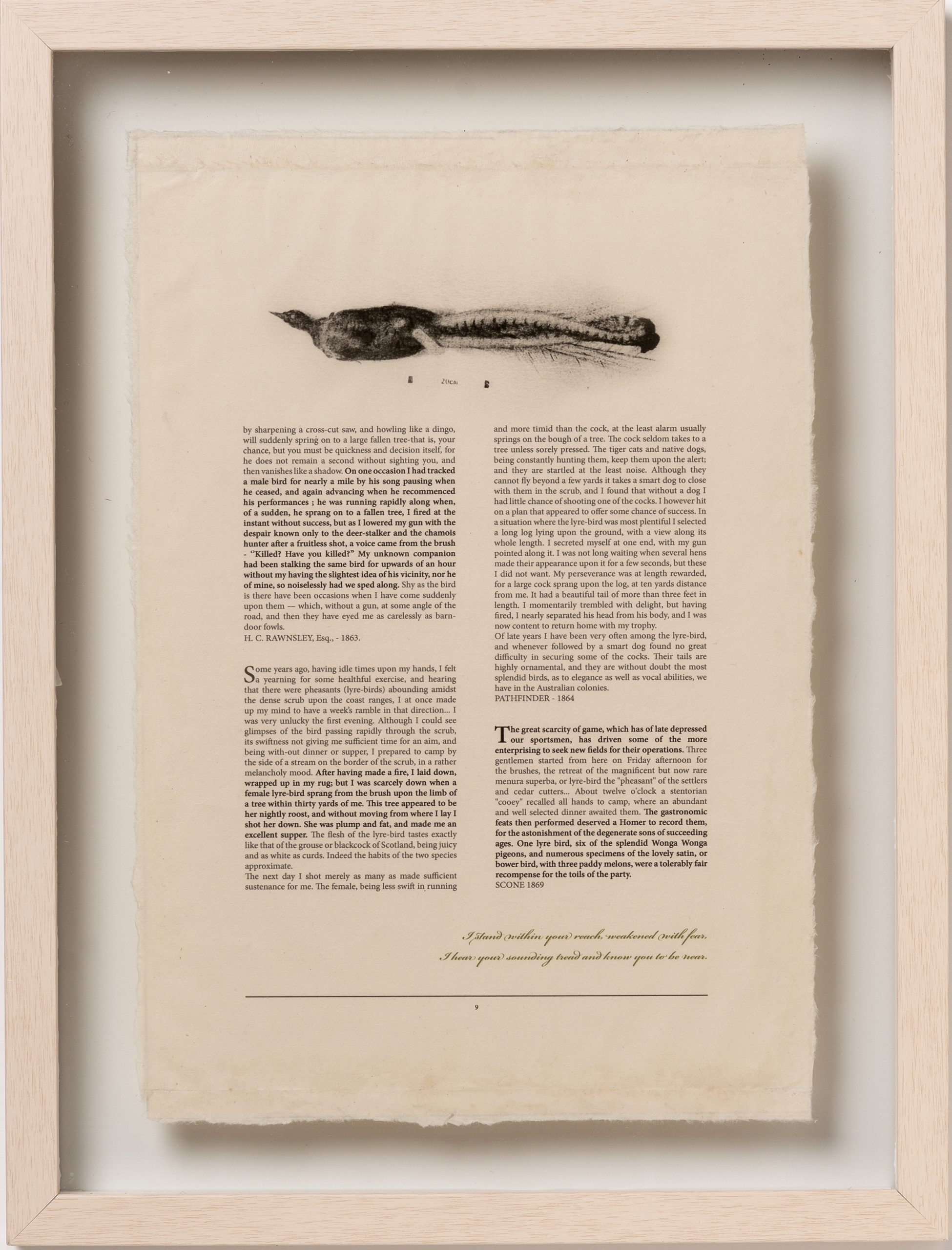

Wayne Thorpe, Gunnai Custodian, Storyteller, linguist and teacher directed me toward a particular study of the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae). The study by Nugent et al. (2014) revealed the ecological significance of the lyrebird: reducing forest fuel loads by twenty-five percent through foraging, significantly mitigating wildfire capacity. Lyrebird foraging also contributes to the nutrient cycling of the forest floor by turning it over every twenty months and breaking down the leaf litter faster (Ashton & Bassett, 1997). Known as the “ecosystem engineer,” this is one player “playing its part.” As Donna Haraway (2016) has explained in her conception of the Chthulucene, playing your part speaks to tentacular webs, nets and networks integral to all lives and stories. While the lyrebird is “saving human lives” through forest fuel reduction, it’s also interfaced with the stories and lives of the-more-than human world, by literally (albeit slowly) moving the largest of mountains, to generating the smallest of microbial activities. Furthermore, the lyrebird has played its part in deep timescales, traversing the earth for at least fifteen million years (Callahan, 2014). The lyrebird draws us away from the anthropocentric story into the world of multispecies studies, mutualities and symbiosis. Where, as Tom van Dooren et al. (2016) observe, connectivity between all biological lives and even “non-living” entities (rivers, mountains, rocks) are considered within the matrices of histories and of things becoming, coevolving and being entangled.

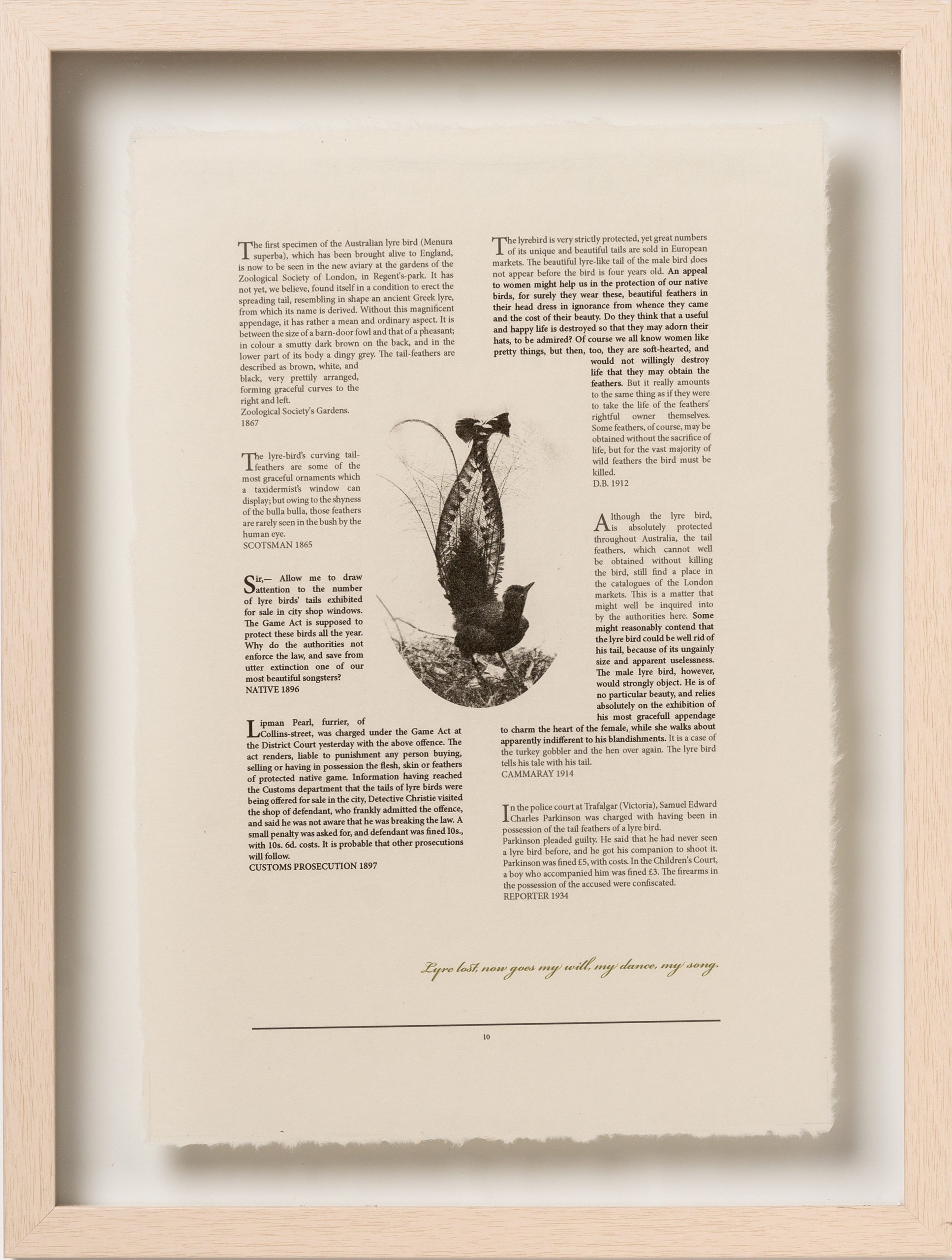

The Lyrebird and the Archive

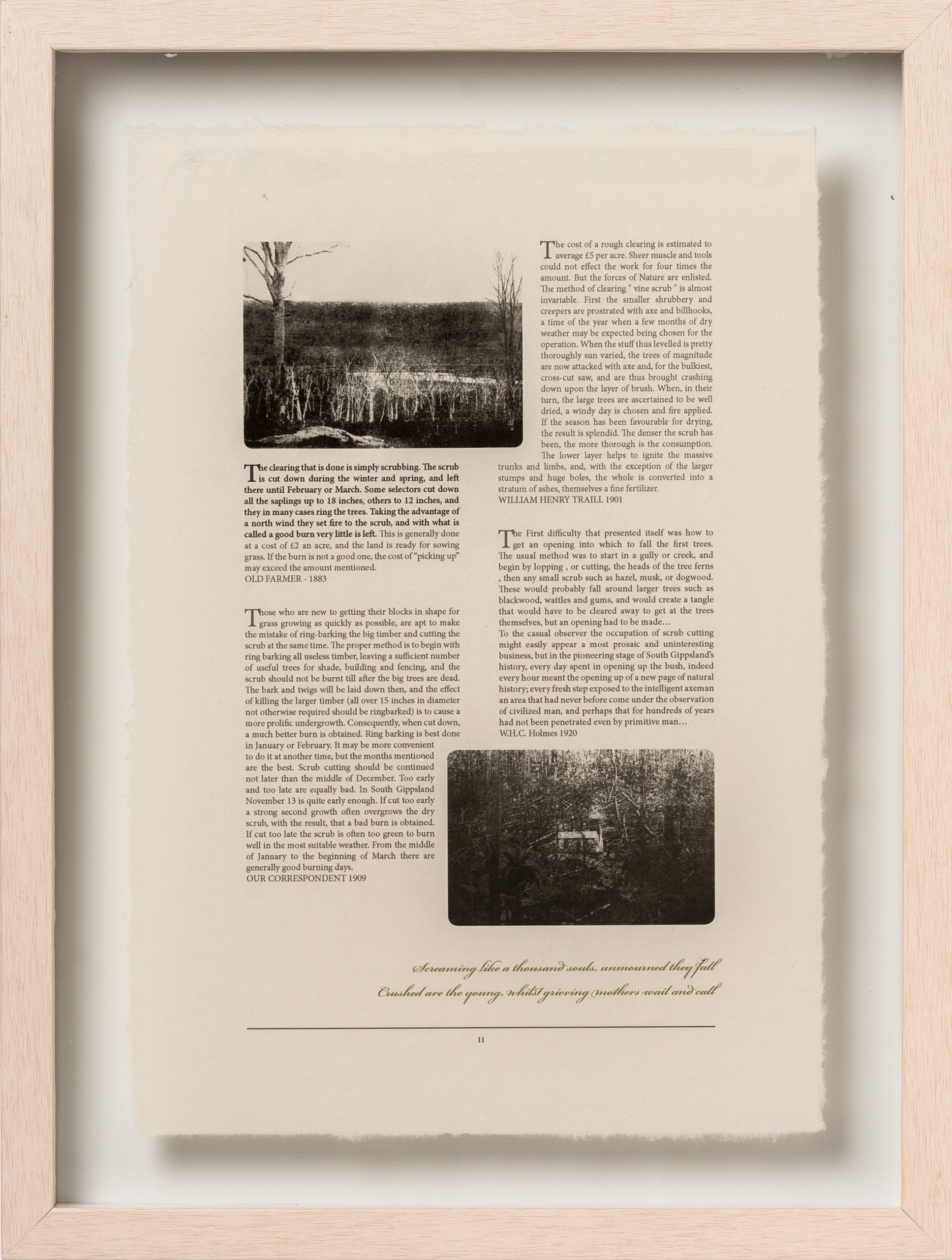

Like so many other animals of the Antipodes, the lyrebird featured prominently in the archives. Photographs, drawings, zoological descriptions, poetry, sporting advice on hunting and methods for cooking the lyrebird emerged. Indeed, from the fashions of London to the camp kitchens in the mountain ranges, the shy lyrebird was omnipresent. As the lyrebird story began to unfold in the archives, it instilled a deeper understanding in me, of the colonisers’ role in razing these matrices through their homogenisation and mono-culturising of these complex and diverse webs, by desiring their pastures and plantations. As I followed the lyrebird line of enquiry, I became immersed in rich textual material and new bodies of knowledge that spanned archival, scientific and critical enquiry. In an antique shop I encountered The Land of the Lyre Bird, first published in 1920 (South Gippsland Development League, 1966). With Wayne Thorpe’s words in mind, I skimmed the pages of this newly treasured object. Profuse with recollections from Gippsland the impenetrable scrub and awe-inspiring forests were being usurped by the colonial hand and their hostile tool, as Mr J. Western writes as he reflects on his “settlement” 1883:

I shall never forget my first impressions of this great forest as we went on that day. The trees towered up till their tops seemed lost in space. The dense jungle scrub underneath, and here and there fern gullies of exquisite beauty, and over it all there reigned a strange and oppressive stillness, broken only by the notes of the lyre bird. … In after years, when we had been brought to fully realise the stupendous task undertaken in reducing this forest, one is amazed at the light-hearted way it was entered upon. Never in any part of the world have I seen a forest of such magnificent proportions – tier after tier of growth from tangled of wiregrass and swordgrass, to fern-tree and scrub, and on to towering gumtree, giving a perpetual twilight by day and black darkness at night…

Though it was an abnormally wet Summer, we got some fine weather in February, and near the end of the month scored a very good burn. What a great fire it seemed to our new chum eyes, and how it seemed to lick up the great tangle of scrub. One cannot easily forget the joy and excitement of for the first time scampering across that 100-acre clearing. Hot foot indeed! for we were all over it while the ground was still covered with the burning embers and the air full of smoke. What a change two hours of fire had wrought! We were forest dwellers no longer (pp. 268-271).

The often-limerick reminiscences were in a strange way beautiful in their modes of memory speech, but the content was deeply melancholic, as their words were mediated to me one-hundred years later. I felt a deep sense of loss in the pages as I began to recall so many colonial paintings in which the artist might paint one fallen tree alongside its frontier hero, or capture the gentleman’s park or the “splendorous” bush, but why never a field of scorched earth? Western describes their gaiety traversing the razed landscape with childlike enthusiasm, but in some respects, like so many of the colonial journals, the nostalgic tones of the coloniser apprehends the whispers of regret. It was here with The Land of the Lyre Bird in hand, that I mused over the ways in which a story told from the perspective of the lyrebird could offer a counter voice to the colonial archive. To subvert the dominant discourse of the coloniser, to “witness” these encounters with the land and resituate them within the histories of disavowal.

The Lyrebird as Linguist

While storying I had been thinking of the lyrebird as a mimic (as it is commonly referred), but when I was talking to Wayne Thorpe about my work, he said that the lyrebird is not a mimic or a stupid animal, rather it is a linguist, and by citing various recordings that had been conducted across different lands he revealed how the lyrebird speaks the language specific to the lands it is on. This completely de-stabilised my own mind/matter, human/nature dualisms, a critical flaw of the Eurocentric, Enlightened subject, a flaw I had not really identified as present or encoded in my thinking until this point (Plumwood, 2005). I wondered if indeed what I was doing was unlearning and disentangling the anthropocentric, mind/matter nature/culture dualism, by mediating such shifts within myself in ways that I could understand through my creative practice.

The lyrebird’s role as a linguist places it in position to bear witness. If we listen carefully the lyrebird will tell us the story of the bush. If a tree has been cut down (hear the chainsaw roar), if other humans have passed (hear the camera click), or if predators have entered (hear the dog howl). The lyrebird speaks the stories of the bush and is witness to the comings and goings of other players. As much as some humans might situate themselves as the only researchers of living things and the only storytellers of other lives, the lyrebird gently reminds us that we are not and points us away from the myth of the anthropocentric.

Over the course of my research, the lyrebird became a symbol of hope and despair. Initially hope, because the lyrebird survived colonisation, even with the swift deforestation and the colonisers’ desire to hunt the prized bird. Despair, with the recent bushfires in Australia (2019–2020), which has now cast doubts once again on its survival. The lyrebird was a means for me to “stay with the trouble” and acknowledge the immense contribution of other players in the lands that I inhabit (Haraway, 2016).

References

Ashton, D. H., & Bassett, O. D. (1997). The effects of foraging by the superb lyrebird (Menura novae‐hollandiae) in Eucalyptus regnans forests at Beenak, Victoria. Australian Journal of Ecology, 22(4), 383-394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.1997.tb00688.x

Callahan, A. (2014). Creature feature: The superb lyrebird. Nature New South Wales, 58(3), 26-27.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Nugent, D. T., Leonard, S. W. J., & Clarke, M. F. (2014). Interactions between the superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) and fire in south-eastern Australia. Wildlife Research, 41(3), 203-211. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR14052

Plumwood, V. (2005). Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason. Taylor & Francis.

South Gippsland Development League. (1966). The Land of the Lyrebird: A Story of Early Settlement in the Great Forest of South Gippsland. Shire of Korumburra for the South Gippsland Development League.

Thorpe, W. (2018, 17 October). The Story of My Life In Wayne Thorpe Tells His Story. https://www.facebook.com/ABCGippsland/posts/podcast-wayne-thorpe-tells-his-story-gunai-man-and-indigenous-linguist-wayne-tho/10156207496334825/

van Dooren, T., Kirksey, E., & Münster, U. (2016). Multispecies Studies: Cultivating Arts of Attentiveness. Environmental Humanities, 8(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3527695

About the Author

Louisa Waters’ practice is concerned with the space where history and landscape intersect; where memories and discourses produced by people and places create ideology, and how ideology transforms land and informs notions of place. She is a PhD candidate at Charles Sturt University.

To cite this creative work

Waters, Louisa. “The Land of the Lyrebird and the Queen’s Colony 2020.” Fusion Journal, no. 19, 2021, pp. 188-205. http://www.fusion-journal.com/The Land of the Lyrebird and the Queen’s Colony 2020/

First published online: March 2021